Four major challenges to achieving the Quintuple Aim are addressed in dedicated sections of this report. They are unplanned ED closures, ED crowding, acute and chronic disasters, and disruptive forces in a rapidly changing world.

How this Report is Designed

This Executive Summary outlines the five sections and fifteen chapters in this report, and includes roadmaps to address the problems our health system is facing and 30 key recommendations for system improvement. Each chapter concludes with its own recommendations, with a consolidated list of chapter recommendations at the end of the report.

Section One (Chapters 1 and 2) is a broad overview of the healthcare system—past, present, and future—from an EM perspective. It provides context for the subsequent sections, which focus on essential elements of system redesign in more detail.

Chapter 1: Where Are We Now? How Did We Get Here? What Must We Remedy? What Will Guide Us?

This chapter looks at what is happening in our EDs now, the root causes of these challenges, and the necessary steps to create a better future. The key concepts of system-wide access block and accountability frameworks are introduced, then discussed in detail in subsequent sections. Finally, core values and guiding principles for a redesigned system are established.

Chapter 2: What Have Emergency Departments Become and What Should They Be?

Many Canadians cannot get timely access to primary, specialty or diagnostic services. As a result, EDs increasingly provide services for which they were not designed. What types of non-emergency care are contributing the dire state of our emergency departments, and why is the ED the wrong place for many patients? We outline a better way, where patients and populations are properly aligned with the services they need.

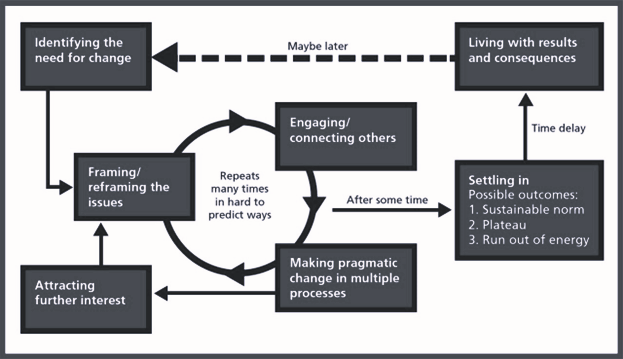

Section Two (Chapters 3-6) addresses unplanned ED closures in the context of clinical services planning, which is all too often oriented around siloed services, rather than patient needs. It proposes a needs-based approach to the number, distribution, capabilities, connections, and staffing of emergency care access points within emergency care systems.

Chapter 3: ED Categorization, Quality, and Standards is about defining and categorizing EDs and urgent care (UC) centres within a network and geographic area. Better planning decisions can be made once ED and UC services are classified in relation to their geography and the demographics they serve. The chapter also discusses the potential for peer-to-peer virtual care to impact clinical services planning. We strongly advocate for EDs to meet minimum quality standards around equipment, staffing, and transition-of-care pathways. Without standards, a system with extreme capacity, staffing or fiscal pressures may be tempted to blur quality lines in the name of ED access.

Chapter 4: Competencies, Certification, and Teamwork explores staffing, the importance of competencies, the role of certification, and how we can optimize scopes of practice to improve care. There are several pathways in emergency medicine to ensure physicians and other care providers have the required knowledge and skills in a rapidly evolving discipline. An approach to fostering high-performance multi-disciplinary teams is discussed, with an emphasis on clear goals and roles, core values, leadership, and simulated practice. Finally, this chapter expands on the concept of communities of practice, and how they can advance quality, recruitment, retention and morale.

Chapter 5: System Integration emphasizes the key principles to successfully integrate and coordinate our health system. The focus is on the relationships between three levels of care in system redesign: primary, urgent, and emergency. The concept of multi-option EMS is developed, and the essential role that pre-hospital care and expanded-scope paramedicine can play in the future. Having on-call specialists and integrated systems for trauma and stroke care (among others) is also emphasized, which is especially true for large rural expanses of Canada.

Chapter 6: Emergency Physician Resource Planning pulls together recommendations from the preceding three chapters into a practical and immediately relevant emergency physician resource planning framework, which could be implemented at a national level. The approach emphasizes a demand-based (what do our populations need?), behaviour-informed (how do physician career decisions impact the workforce?) approach to health human resource planning for the future.

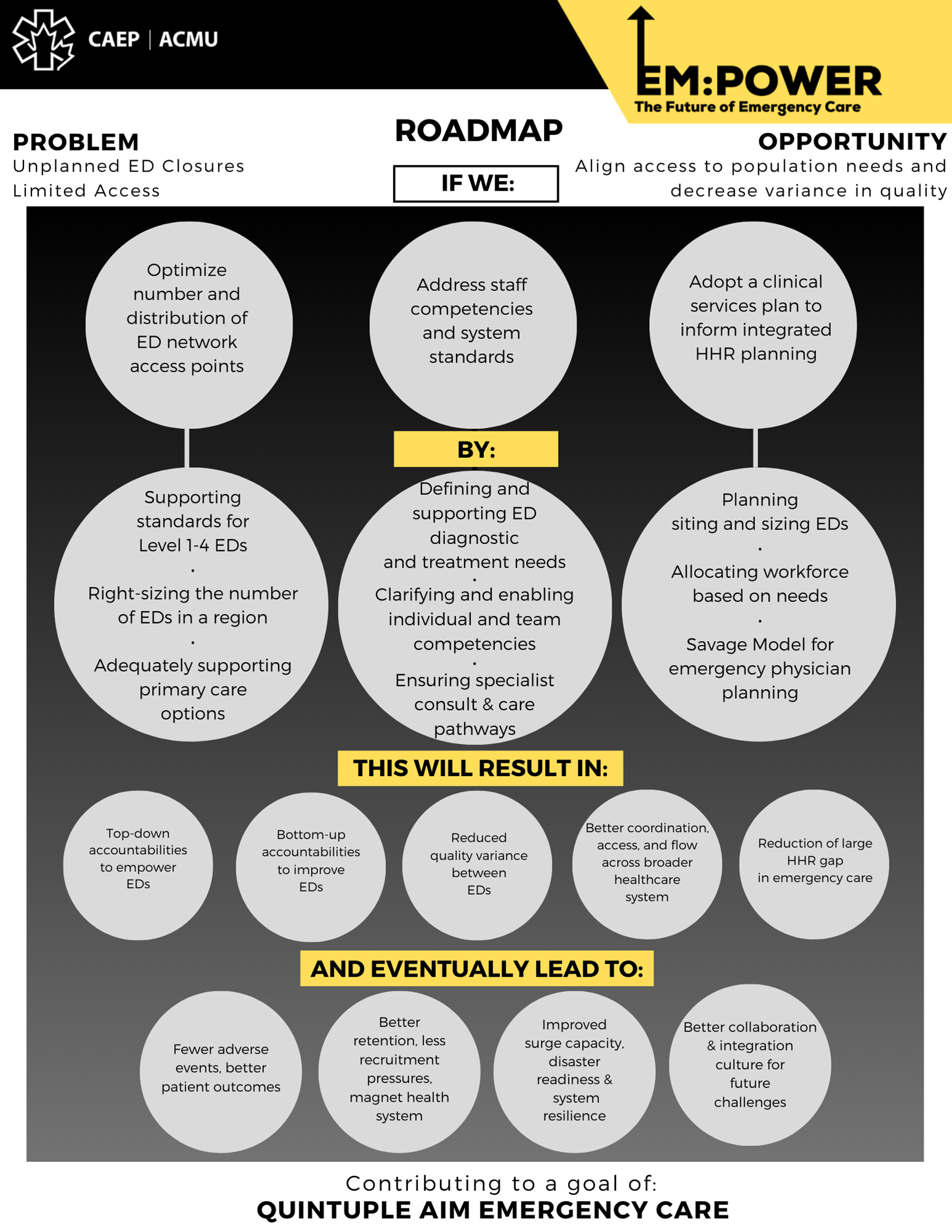

Section Three (Chapter 7) focuses on ED crowding and system-wide access block as the main problem for Canadians seeking emergency care and the primary symptom of health system dysfunction. It discusses ED role definition, the importance of patient care accountability frameworks, and strategies for improving access and flow at a whole-of-system level.

Chapter 7: Access Block and Accountability Failure.

We have the highest rate of emergency department use, compared with 11 other affluent countries. Why do patients wait—sometimes for days—on stretchers in hospital hallways? This chapter addresses root causes, which include the absence of patient care accountability and lack of planning to address care gaps in our healthcare system.

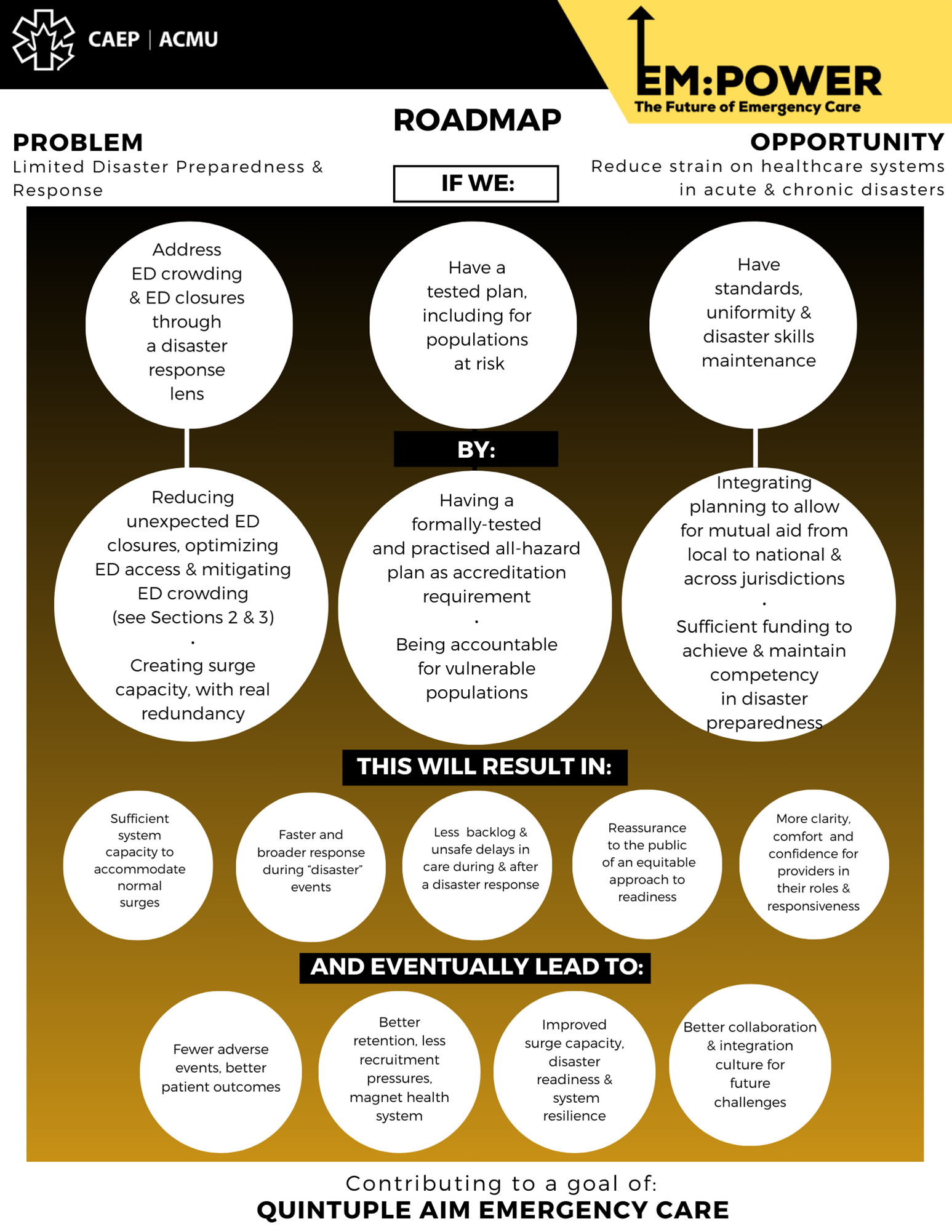

Section Four (Chapter 8) addresses disaster management, emergency preparedness, and system resilience, as well as the necessary integration, education, and training to assure disaster readiness. It outlines how disaster preparedness is applicable to our current state, re-emphasizes lessons learned from COVID-19, and makes pragmatic recommendations to improve our response to similar scenarios in the future.

Chapter 8: Disaster Preparedness.

If Hurricane Katrina happened in Canada, how would we cope? The truth is, we are not ready and our system suffers from an absolute lack of adequate preparedness. Many Canadian emergency departments are effectively in disaster status all the time, but lack the tools to cope. This chapter provides a roadmap to equip our front lines to deal with their current overburdened situation and keep them ready to face an eventual catastrophe.

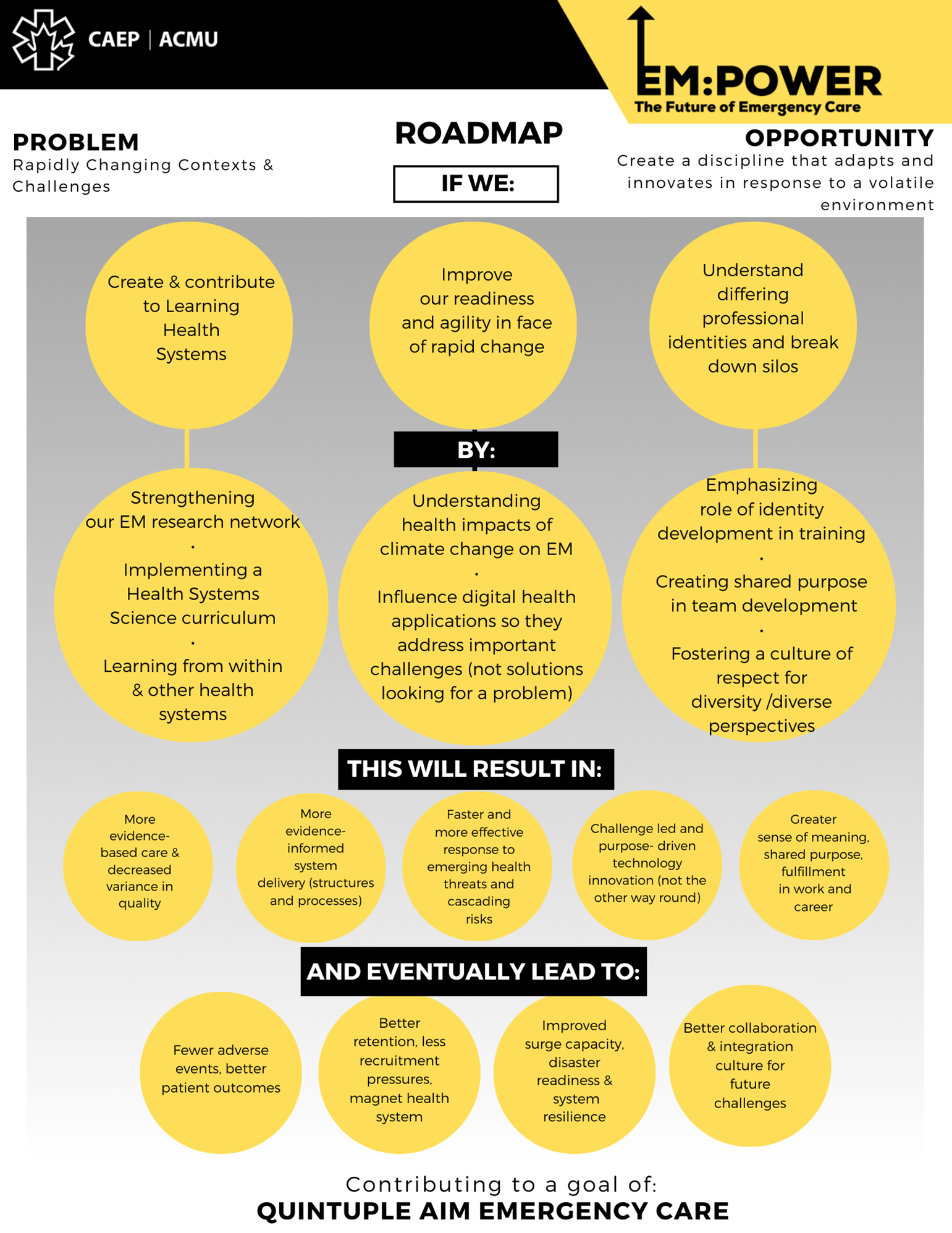

Section Five (chapters 9-15) covers a spectrum of global trends and disruptive forces that will reshape and reorient emergency care, research, and education in the decades to come. This includes digital health and advanced technologies, JEDI (justice, equity, diversity, and inclusion), climate change, and lessons from other (higher performing) healthcare systems.

Chapter 9: Coevolving in the Research and Quality Ecosystem

Just as we’ve done for clinical care, we begin with an exploration of integrating EM research into a broader system. This underlines the importance of tailoring research efforts to the biggest threats to our patients, populations, and planetary health.

Chapter 10: The Future of Digital Health (DH) in Emergency Medicine

DH will transform medicine in a future not too far from now. The question isn’t whether DH will be adopted, but rather how technology can help forge a path to achieve the Quintuple Aim of improved patient experience, better population outcomes, lower costs, an empowered workforce, and health equity for all Canadians.

Chapter 11: Managing Intergroup Relations

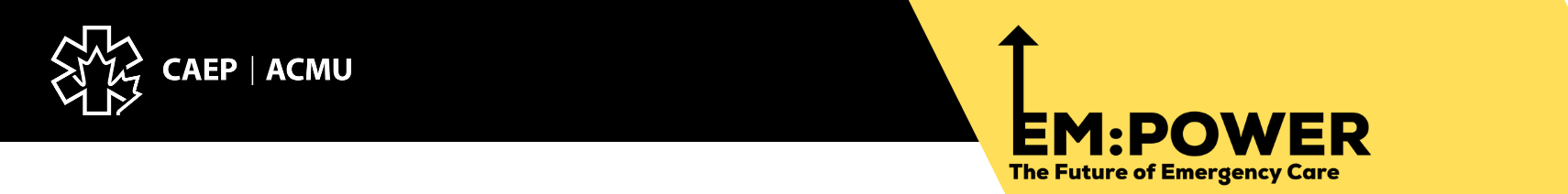

Collaboration across silos is notoriously difficult to achieve, and efforts to spread better practices or change outmoded structures often screech to a halt at intergroup boundaries. The problem of intergroup conflict is so glaring, and so pivotal to ED–system relations, that it seemed essential to devote a chapter to this topic. Counterintuitive as it may seem, change can take place by working through social identities, not against them.

Chapter 12: Emergency Medicine’s Future Role in Health Policy and Public Affairs

It will take more than words—however well-intentioned and informed—to produce meaningful change. That’s where engagement in policy, public affairs and advocacy begins. Emergency physicians work at a critical healthcare intersection, the junction between community, prehospital, primary, and acute care. We can be powerful agents of change, observing, anticipating, and responding to the health issues of the day, with a voice that resonates across the entire medical system. Strategies arising from this report must be based on a clear, depoliticized, long-term vision, with short, medium, and long-term objectives. This avoids the one-problem/one-solution trap that ultimately fails and reverts to emergency backlogs.

Chapter 13: Emergency Medicine in the Era of Climate Change

Climate emergencies are already increasing in frequency and severity. Emergency programs must understand local climate risks, along with the need to adapt their operational plans. ED directors must be aware of the temperature and precipitation projections for their region, plan for the consequent operational impacts, and work with climate-savvy architects and engineers to design infrastructure for a changing environment. CAEP and its members also have an important role in education and advocacy for a healthy planet.

Chapter 14: Building on Values: Justice, Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion (JEDI) in Emergency Medicine

Many diverse and marginalized populations do not feel safe accessing care in the ED, often sensing that they are not heard and their needs not addressed. As respected members of society, physicians can and should be powerful advocates for social justice to ensure healthy living conditions for all. This chapter will outline some of the ways we can do so, with a focus on ED staffing, leadership, and care of marginalized populations. Also addressed is the importance of representation; it has profound impacts on how people view and use the system, trust providers, and adhere to healthcare recommendations that affect patient outcomes.

Chapter 15: Lessons from Other Healthcare Systems

ED closures, crowding, patient morbidity, mortality, dissatisfaction, and healthcare worker burnout are not unique to Canada; other countries with better-performing healthcare systems are similarly challenged. Using case studies, this chapter compares health policy approaches from several OECD countries, and identifies potential best practices, covering workforce planning, system capacity, and long-term care. Private vs. public care is also examined.

Below are EM:POWER Roadmaps, depicting solutions to four major challenges to achieving Quintuple Aim-level emergency care. Each of these is explored in detail in a dedicated section of this report.