Section Editor: David Petrie

One System, With Many Access Points

Overview

Chapter 3: ED Categorization, Quality, and Standards is about the categorization of EDs (and urgent care centres) within a network and geographic area. A plain-language, four-level nomenclature for EDs in Canada is recommended, based on population-weighted distances, and other system level goals. It discusses the potential for peer-to-peer virtual care to impact clinical services planning—the siting, sizing, and synergizing of EDs. We strongly advocate for EDs to meet minimum quality standards around equipment, staffing, and transition-of-care pathways. Without standards, a system with extreme capacity and fiscal pressures may be tempted to blur some quality lines in the name of access.

Chapter 4: Competencies, Certification, and Teamwork explores the issue of staffing, the importance of competencies, the role of certification, and how we can optimize scopes of practice to improve care. There are several pathways in emergency medicine to ensure physicians have the requisite (relative to the level of ED categorization) competencies in a rapidly evolving discipline; likewise for nurses, paramedics, and advanced care providers, such as nurse practitioners and physician assistants. The art and science of fostering high-performance teams is also discussed, with an emphasis on clear goals and roles, core values, leadership, and simulated practice. Finally, this chapter expands on the concept of communities of practice, and what they can do to advance quality, recruitment, retention, and morale.

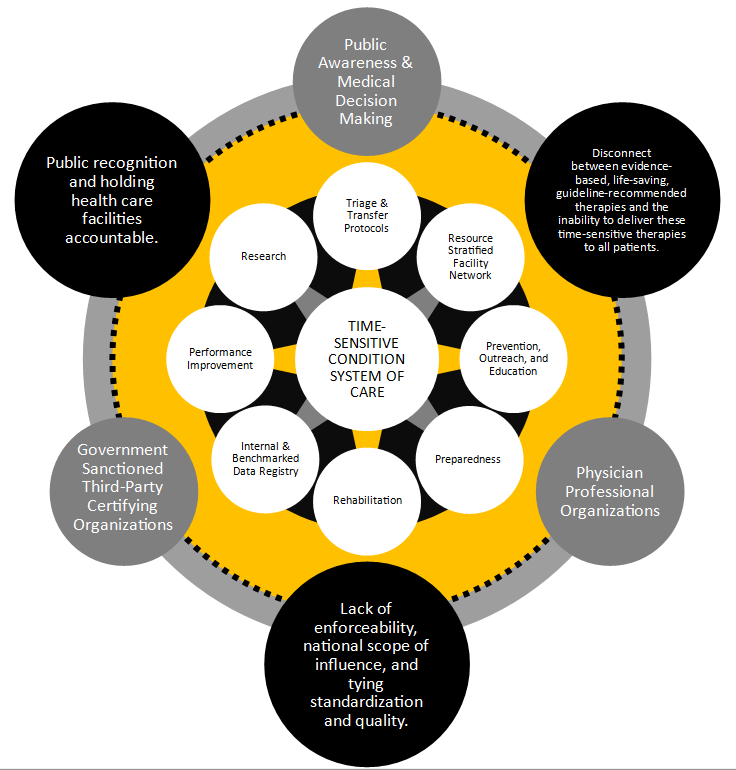

Chapter 5: System Integration emphasizes the key principles for successful health system integration and coordination. The focus is placed on the relationships between three levels of care in system redesign: primary, urgent, and emergency. This chapter develops the concept of multi-option EMS, and the essential role that pre-hospital care and expanded-scope paramedicine can play in the future. The availability of on-call specialists in an integrated network of emergency care is also emphasized, which is especially true for large rural expanses of Canada. Also highlighted are the importance of systems that deal with trauma, poison-care, myocardial infarction/stroke, etc. in improving patient and population outcomes.

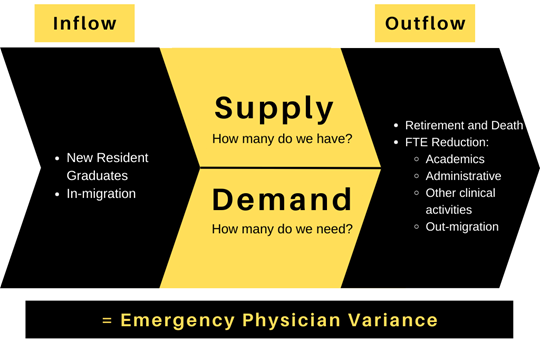

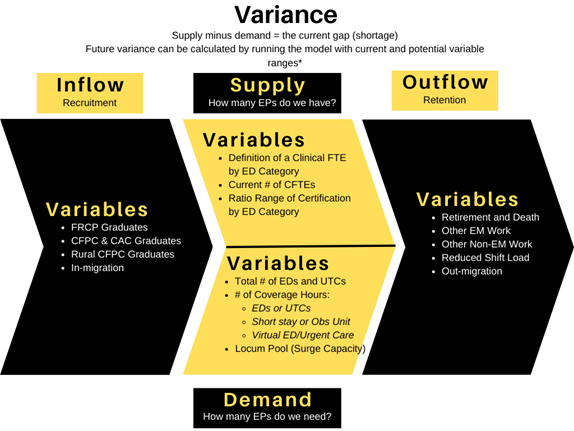

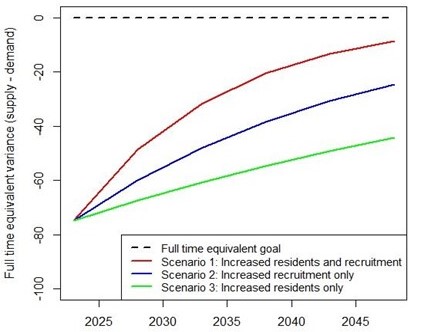

Chapter 6: Emergency Physician Resource Planning synthesizes the recommendations of the preceding three chapters into a practical and immediately relevant emergency physician resource planning framework (the Savage Model) that can, and should, be implemented at a national level. This approach builds on previous work that emphasizes a more demand-based (i.e., what do our populations need?), behaviour-informed (e.g., how do MD career decisions impact the workforce?), iteratively implemented and adjusted approach to HHR (Health Human Resources) planning for the future.

Chapter 3: ED Categorization, Quality, and Standards

| System design saves lives. |

Introduction

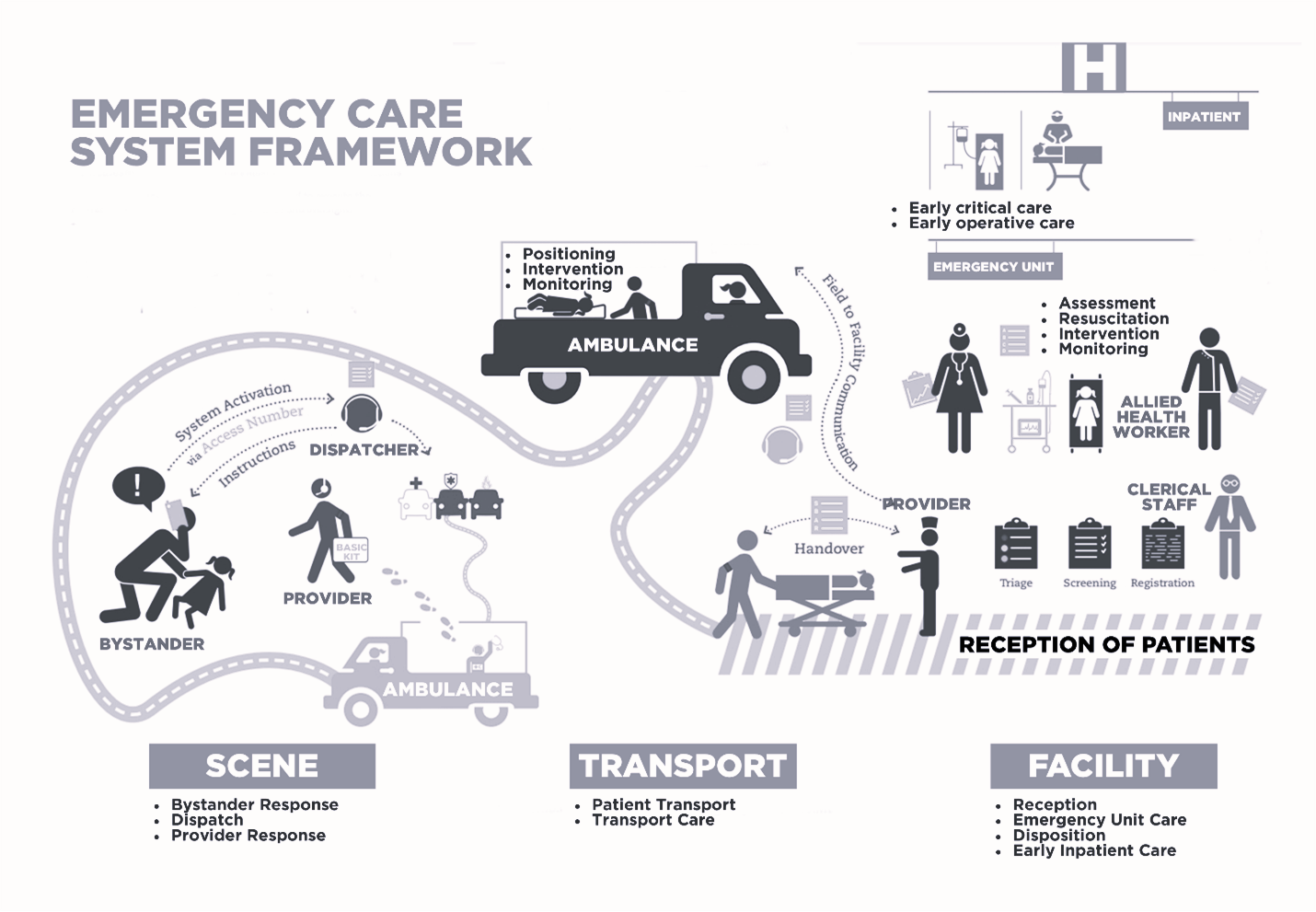

Reliable, accountable, and coordinated Emergency Departments (EDs) are essential nodes in a high-performance network of emergency care. More importantly, emergency care systems (ECSs) are an essential part of Quintuple Aim (value-based) healthcare systems. This is the future Canadians deserve and expect, and proper system design contributes towards that goal.

Across the world, this has not always been the case. In 1966, the American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma published an important document titled Regional Trauma Systems: Optimal Elements, Integration and Assessment Guide. (1) In it, the authors wrote: “the human suffering and loss from preventable accidental death constitute a public health problem second only to the ravages of plagues and world wars” and that the public was “largely insensitive to the magnitude of the problem.”

They went on to say that the development of a mechanism for categorization, inspection, and accreditation of emergency departments on a continuing basis must become a minimum standard in modern healthcare systems. Similar recommendations followed in the service of better cardiac, medical/critical, and pediatric care. These reports helped drive the emergence of a new specialty—emergency medicine.

The Case for Categorization (2)

| Categorization is a process for inventorying, assessing, and cataloguing the emergency care resources, services, capabilities, and capacities of medical care facilities in a community or region, using a criteria-based classification system over a range of emergency care conditions.

This process is used to assist physicians, hospitals, health departments, and emergency medical services (EMS) agencies in making informed decisions on how to develop, organize, and appropriately utilize health care resources for the emergency care system”. [2] |

Why should EDs be categorized? The staffing, training, and services available in small rural EDs are clearly very different from those in a downtown urban emergency department, but from the public’s point of view, they both have the same name. The potential benefits of a national ED categorization scheme include:

- Informing public knowledge, expectations, and use of the system

- Standardizing a health authority or ministry’s responsibility to support the required equipment, medication, and personnel readiness

- Benchmarking quality and performance targets across similar EDs in Canada, and

- Informing a more intentional approach to emergency physician resource planning (covered in more detail in Chapter 6).

A call for categorization was also issued by the US Institutes of Medicine Future of Emergency Care 2006 series, (3,4) and the Society of Academic Emergency Medicine’s 2010 Consensus Conference, Beyond Regionalization: Integrated Networks of Emergency Care. (5) Initial approaches to regionalization improved care in some disease-specific areas, such as trauma. (6) However, regionalization isn’t the same as integration, (7,8) and doesn’t always mean one-way movement of patients to centralized resources. (9) Geographically-organized governance and financial structures in Canada should not be conflated with coordinated, accountable, and responsive care at a population-based, system level.

How far have we come with categorization? And are we starting to slip backwards? Despite the calls for a categorization and designation scheme, or a Regionalism 2.0 approach, (9) little has been done in this country around a common national framework for emergency departments. Different provinces have used different classification schemes, and some provinces have used none. Emergency care systems have evolved organically, and mostly follow population-weighted distances as a guide when building and resourcing EDs, although political expediency has played a role. Do we have too many EDs? Do we have too few? Are they optimally distributed? Can the public be sure that what’s called an ED can fulfill its mission? (10)

To be fair, when categorization has been attempted, most provincial approaches have been broadly similar. While there will always be some variation due to local and/or province-specific contexts, a plain-language and common-sense national framework to guide ED categorization is a critical step in moving towards integrated networks of emergency care in the future. (9)

Canadians expect to understand and trust what they are getting when terms like emergency department are used. Moving forward—if they don’t already exist—emergency care clinical networks (ECCN) (11) or the equivalent should be established in every province/region to lead and coordinate clinical services and HHR planning, as well as to oversee operational decision-making, and quality improvement/patient safety (QIPS) initiatives.

ED Categorization

The International Federation of Emergency Medicine (IFEM) terminology project defines an ED as: “The area of a medical facility devoted to provision of an organized system of emergency medical care that’s staffed by emergency medicine specialist physicians and/or emergency physicians, and has the basic resources to resuscitate, diagnose and treat patients with medical emergencies.” (12)

It is not feasible—nor is it fiscally reasonable—to maintain a tertiary care hospital in every community in Canada. As the medical ethicist Norman Daniels has said, “The social goods we often must provide including… healthcare…aren’t sufficiently divisible to avoid unequal or lumpy distributions—allocation decisions are necessarily messy.” (13) That said, optimizing the number, distribution, and capability of EDs must be made as non-lumpy as possible. A layered, balanced, and integrated approach is important in the clinical services planning of any region or province.

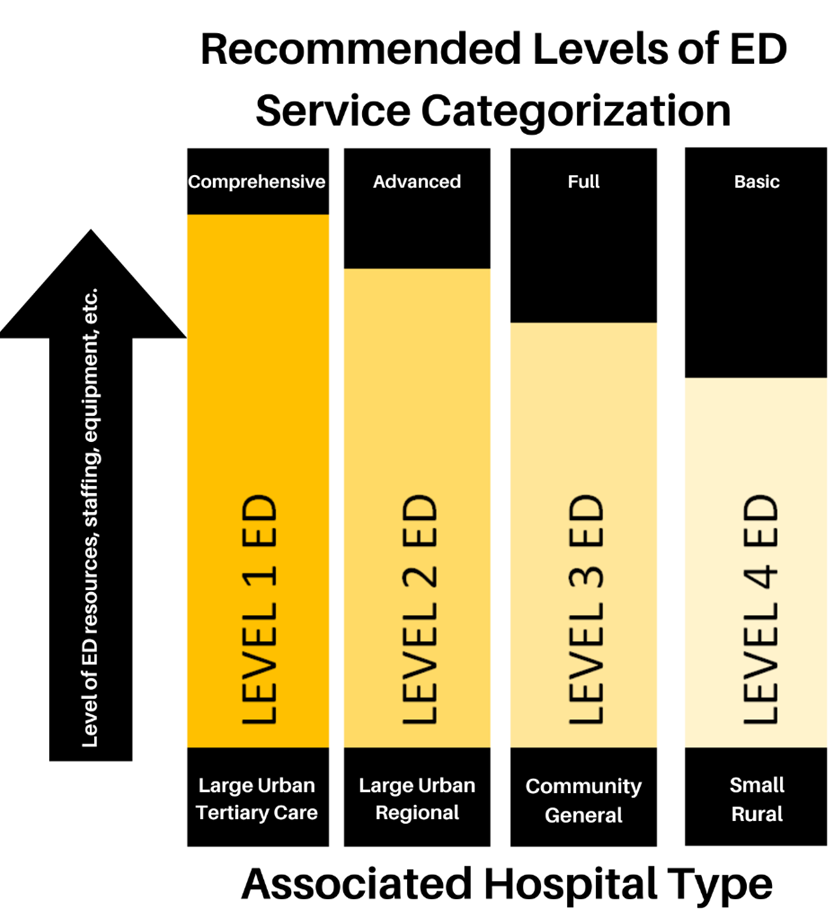

Categorizing EDs is an essential part of that strategy. One model that should be used as a starting point is a simple four-level approach to EDs: Comprehensive, Advanced, Full, and Basic (14) (see Figure 11). Reasonable subdivisions of categories may also be useful, such as a Level 1 Pediatric ED, or a Level 3 Freestanding ED. (14)

Figure 11. Recommended Levels of Emergency Department (ED) Service Categorization

Clinical Services Planning and integrated Health Human resource planning, as well as the EMS system status plan (SSP) and broader system integration issues, requires a rational and intentional approach to ED categorization and standards, as recommended here. To be clear, in this context a Basic level 4 ED still must meet the baseline standards of in-person teams/physician-led resuscitation and stabilization of the acutely ill and injured, they must stay on the EMS SSP, and they must be capable of the initial assessment and treatment of the broad spectrum of unexpected illness and injury in all age groups. If these standards are not met, they should no longer be referred to as an Emergency Department.

A plain language four-level categorization taxonomy should be used (see Figure 11 and specific recommendations below) to help guide clinical services planning. These levels should be Figure 10 determined/assigned by population-weighted distance calculations and be guided by the function they are expected to fulfill in the system. Specific details about the standards expected at each level could vary slightly by province, but general principles need to be set at the national level. Once assigned, the Ministry of Health (MoH) and Health Authority (HA) must adequately fund and support the ED site to meet this function.

EDs must meet the standards consistent with their level of designation. If a hospital posts signage using the term “Emergency Department,” the public expectation, at a minimum, is that the ED—no matter its level—is capable of the assessment and treatment of unexpected, undifferentiated, and time-sensitive illness and injury. The additional assumption is that its staff have the competencies for the resuscitation, stabilization, and transfer out, if necessary, of any patient that arrives, either by ambulance or as a direct walk-in.

Network-Integrated Urgent Care Centres

The role of Urgent Care Centres (UCCs) is expanding rapidly across Canada. (15) Like EDs, the capabilities of UCCs span a wide spectrum, and their clinical services may potentially overlap. Over the last 20 years, these centres have become integral to several urban acute care systems. In metropolitan Calgary, for example, five urban and suburban UCCs annually service approximately 180,000 patient visits, in addition to the approximately 440,000 visits seen by the five adult and children’s hospitals. Similar high-volume UCCs operate in Vancouver, Hamilton, Kingston, and London, and more are developing in many other locations, including Saskatoon, Halifax, Toronto, Montreal, and Ottawa.

While there are currently no nationally-established standards, UCCs typically have the following characteristics: in urban areas they are located outside of hospitals, provide unscheduled care, do not necessarily operate 24/7, and offer a spectrum of services focusing on acute/unscheduled illness and injury of urgent but not emergent need. In most cases UCCs come off the EMS system status plan, and do not receive ambulances. They do provide on-site labs and imaging, medications, and multidisciplinary care. (16,17)

Urgent Care Centres can also be established in rural areas, physically located within hospitals. Again, they are geared towards unexpected/time-dependent illness and injury in the CTAS (Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale) 3-5 range, but not for the more severe CTAS 1,2 patients.

To be clear, the recommendations for UCCs in this categorization framework include:

- They must be operated by hospital corporations or regional health authorities, and therefore have some formal relationship to a nearby hospital and ED.

- They must also be integrated with regional clinical services plans and Continuous Quality Improvement (CQI) programs.

- This integration is to differentiate them from privately-owned and operated transactional retail clinics that exist on the spectrum which range from walk-in clinics to direct-to-patient virtual ERs.

While “Urgent Care” from a public perception allows it to remain distinct from EDs, the Canadian experience demonstrates that their utility and impact on the delivery of acute care here is complementary. Because of this, we believe that clear standards must exist for the structure, processes, equipment, and provider competencies for Network-integrated Urgent Care Centres, just as they must when we categorize emergency departments.

Peer-To-Peer Virtual Care

Peer-to-peer virtual care will play an increasingly important role in the evolving design of emergency care systems. In the context of categorization definitions, peer-to-peer programs, like RUDi (Rural Urgent Doctors in-aid) (18) in BC and TRON (19) (the critical care rural support program in Ontario), can fulfill a crucial function for a site to maintain its designation as an ED. They could also strategically become a Network-integrated Urgent Care Centre, local out-patients department, or nursing station.

Designation and categorization of EDs in an integrated network of Emergency Care is only the first step. Concurrently, ED standards must be associated with each level. Chapter 5 addresses the even more important issue of integration, examining how the various network nodes and access points to the Emergency Care system interface, connect, and transition patients through their journey across the broader healthcare system.

Pediatric and Geriatric Considerations

The ethos of emergency medicine is its readiness to care for anybody from 0 to 100+ years of age. However, two cohorts that require special consideration are the care of children, and the care of elders within our system. Some of this readiness is embedded in the general system design and integration principles discussed further in this section, and some are specific to pediatrics and geriatrics (see Appendices 3 and 4 at the end of this report).

More children in Canada receive their emergency care in EDs associated with general hospitals than in urban tertiary care pediatric emergency departments. Pediatric emergency care systems have been early adopters in creating integrated networks of care through EMS transport connections, and peer-to-peer telemedicine supports. TREKK (20) is a freely-available collection of online resources for front line providers who are caring for ill and injured children. The network demonstrates the power of national projects to effectively support the real-time, clinical decision-making that takes place across the country. These approaches should be funded and strengthened in the future. Additionally, emphasis should be given to provide more and better pediatric emergency care training experiences for learners, as well as the maintenance of competence opportunities to improve the proficiencies of all types of emergency care providers (paramedics, nurses, physicians, etc.).

The evolving demographics of our Canadian population are well known. We are now on the leading edge of a significant rise in the number of elderly patients who will need medical and emergency care services. This increases the necessity to develop and support multi-disciplinary healthcare homes that are closely integrated with home and community care options and have mobile and virtual connections if needed (see System Integration, Chapter 5). Improved access to better quality long-term care is part of the equation, but only after all home and community care options have been exhausted. Emergency care systems will need to improve their approach to elder-friendly care spaces and options. In addition, geriatric competencies for all providers must be increased, with specific geriatrics clinical pathways and access to geriatricians when required.

ED Consolidation and Distribution: A Polarity Management Approach

Once categorized, where should EDs and Network-integrated Urgent Care Centres be placed to optimize care? Planning and implementing the number, distribution, capabilities, connections, and workforce in an integrated network of care will require an approach that balances issues viewed to conflict with each other. Polarity management is used to solve unsolvable problems when solutions on each end of the spectrum have trade-offs. Closing or relocating EDs are examples of this type of tension; potential trade-offs are ever-present, and there will always be some degree of tension around these network system decisions.

illustrates these pressures and the various trade-offs in access, quality, and costs when the optimal geographic distribution of emergency care access points is under consideration. Using this framework to evaluate an existing system can fuel the creative energy for change. It’s essential for provincial emergency care clinical networks (ECCNs) to monitor, evaluate, and modify these trade-off decisions over time to evaluate whether they’re ultimately improving patient outcomes in a cost-effective manner — i.e., are they consistent with a value-based healthcare system? (10,21)

ED Access And Quality: A Polarity Management Approach

Media coverage on delays in access to emergency care has dominated the news headlines for over a decade and highlights a major problem. Demand for care in Canadian emergency departments has far outpaced the growth in population, leading to stress in the system and societal expectations that cannot be met. The immense public and political interest are often singularly focused on wait times. This relentless focus on a single dimension of quality may force decision-makers, individual healthcare providers, and payers to ignore other important elements of safe care. Over time it additionally has the potential to degrade the quality of treatment provided in the ED.

In their updated position paper on quality and safety in emergency medicine, (12) IFEM wrote that on arriving in an ED, patients should expect that their care will be provided by the right personnel, making the right decisions, following the right processes and approaches, in the right environment, in the right place, in the right system, with the right support. They go on to say that in countries like Canada, where emergency medicine is established, patients should also expect early and reliable access, as well as support from specialist in-patient, out-patient services, and critical care expertise. Appropriate durations of stay in the ED should be expected, together with the development of related EM services, such as short stay/observation pathways, social and mental health services, and options for outpatient follow-up.

IFEM also describes five enablers and barriers to quality care in the ED:

- ED staff: are they trained, qualified, and motivated to deliver effective and efficient care in keeping with national guidelines?

- Physical structures: is there the appropriate size and numbers of treatment rooms/areas, and triage, and waiting space? Are there fail-proof equipment, well-stocked consumables, and IT systems (with back-up)?

- ED processes; are there validated triage systems, access to clinical practice guidelines, and appropriate policies and procedures?

- Systems approach; are there coordinated and accountable pathways prior to, during, and after their ED care, and are they seamlessly integrated and appropriately resourced?

- Monitoring outcomes; is there an appropriate gathering of, synthesizing, and interpreting of data, especially patient-oriented outcome data? And how is that data feeding back into the iterative improvement of value in a Learning Health System? (12)

Six Dimensions of Quality in Healthcare

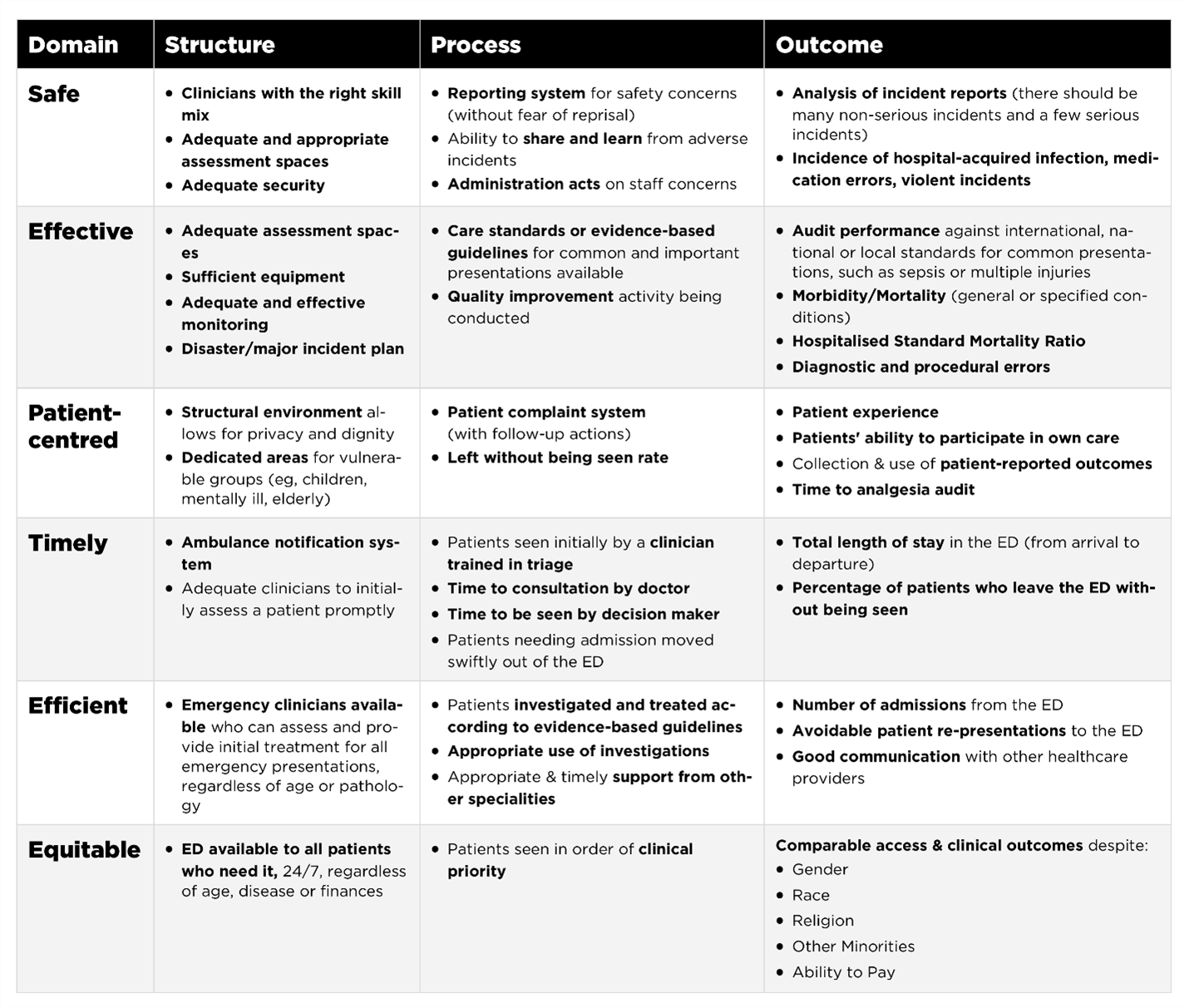

The Institute of Medicine states that the quality of care is the “degree to which health services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes and are consistent with current professional knowledge.” The Institute goes on to define the dimensions of quality as being safe, effective, patient-centred, timely, efficient, and equitable. Hansen et al (12) suggest several potential quality indicators for the ED system, mapped to each dimension in Table 2.

Table 2. From Hansen et al. (12) suggested indicators for EDs, grouped within structure, process, and outcome to address the six Institute of Medicine domains of high-quality care. Canadian citizens deserve and expect emergency care that’s successful in all the dimensions of quality.

Data and Quality Care Indicators

It is common to use data to determine improved outcomes, cost effectiveness, accountability, safety or even satisfaction in the care provided. Information is collected in a variety of ways throughout the system. This includes reviews of patient medical charts, use of large databases, findings from local quality or patient safety meetings, patient feedback files, safety event reporting, accreditation surveys and patient registries. (22) These metrics provide a window into the quality of healthcare delivery and must be chosen carefully.

Alarmingly, most provinces in Canada monitor only markers of timely care, with reports expressed as averages or percentiles. Metrics such as “Initial Time to Physician Assessment”, “Overall ED Length of Stay” and “Ambulance Offload Time” dominate reports. Although these time markers give some information about patient movement through the system, they do not provide any insight into other aspects of quality. There are some audits on outcomes or adherence to guidelines at the individual hospital or regional levels, but no national repository of data or benchmarks for much of it. This is a major problem in planning and evaluating emergency care in Canada.

Standards

Standards are essential to maintain public trust, and to guide future policy direction and resource allocation decisions. In business, standards can refer to goods, services, and systems; they ensure safety, quality, and consistency which are fundamental to trade. In healthcare they play the same role and are fundamental to quality care. Without standards and definitions, rules become fuzzy, health system redesign becomes sketchy, and public trust can be undermined. Innovation and creativity can push the resistance of a conservative or stuck system, but there must be an ongoing commitment to do no harm, and to improve value in the system where value = quality/cost.(23)

Standards establish minimum levels of performance and consistency across multiple individuals and/or organizations. Minimum standards for hospitals and health authorities are the jurisdiction of Accreditation Canada, but the specific standards around EDs—and more broadly emergency care systems—are not well defined.

Other countries, such as the UK, have invested in creating baseline standards in emergency and urgent care, though many are still narrowly focused on time-based measures. (24,25) The Australasian College of Emergency Medicine has defined national minimum standards on cultural safety, clinical care pathways, administration, professionalism, education/training, and quality improvement. (26) CAEP’s essential next step is to lead a uniform approach to EM standards for emergency departments and emergency care systems across Canada.

Availability of Curated Standards for Good Practice

The publication of evidence-based tools is commonplace across the country, which may be in the form of clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) or standardized order sets. In British Columbia and Alberta, this work is coordinated on a provincial basis through their ECCNs, (11) where clinical guidelines are available in an easily accessible website. (27) Many other Canadian provinces have created similar repositories or toolkits that are available on local IT infrastructure throughout their region. CAEP also has several guidelines to help direct care. The Translating Knowledge for Kids (TREKK) resource regularly publishes best practice guidelines in emergency care for children, and this is used from one end of the country to the other.

Conclusion

The discipline of emergency medicine is now seriously challenged by the stressors of a supply/demand mismatch in the rest of the healthcare system. The creation of national standards that define acceptable benchmarks for access to and quality of care is an essential next step in ensuring accountability for everyone, from front-line providers to executive-level decision-makers.

Optimizing the number, distribution, capabilities, connections, and workforce in an integrated network of care will require an intentional approach to categorizing EDs, as well as other potential access points to the emergency care system, such as Network-integrated Urgent Care Centres and virtual care.

Access is just one side of the coin; quality and standards are the other. The ethos of quality improvement is embedded in the core values of emergency medicine. (28) It is time to develop and implement a better systems approach (4,29) to emergency care in Canada that balances the best aspects of consolidation and distribution, with additional assurances that quality is not compromised in the quest for access.

Recommendations for ED Categorization, Quality, and Standards

- Provincial health ministries should establish Emergency Care Clinical Networks (ECCNs) to coordinate clinical service and HR planning, operational guidance, and quality improvement-patient safety initiatives.

- A National Emergency Clinical Care Council (NECCC) should be created; endorsed by CAEP, supported by the federal government (secretariate, administration, travel, integration with CIHR etc.), and given a mandate by the Council of Provincial Deputy Ministers of Health to support the EM:POWER recommendations at the provincial level through national collaborations, benchmarking, and sharing of successes, innovations, and lessons learned.

- Provincial ministries of health and/or health authorities should fund and enable these provincial ECCNs and integrate them with the broader healthcare system governance structure.

- Emergency physicians, ideally in a co-lead dyad, should provide leadership to these ECCNs and be given a seat at the appropriate decision-making tables.

- ECCNs should oversee categorization, standardization (facilities, equipment, required competencies) and integration of EDs and other emergency care access points.

- A plain-language four-level categorization taxonomy should be used to help guide clinical services planning:

- Level 1 ED = comprehensive services associated with large tertiary care hospital

- Level 2 ED = advanced services associated with other large urban or regional hospitals

- Level 3 ED = full services associated with community general hospital

- Level 4 ED = basic services associated with small rural hospital.

- These levels should be determined/assigned by population weighted distance calculations, annual volumes, and be modified by the function the ED is expected to fulfill in the system. Once assigned, the MoH/HA must adequately fund and support each ED site to meet this required function. EDs must meet the standards consistent with their level of designation.

- Network-integrated Urgent Care Centres and Network-integrated peer-to-peer Virtual Care (P2PVC) in this context means that these access points to the Emergency Care system must be designed, integrated, and held to the same quality improvement patient safety standards as EDs (one network, many access points).

- CAEP/NECCC should create a national template and example standards for provinces to adopt in the domains of physical space, safety, equipment, DI/lab availability, medication availability, staffing numbers, competencies, professionalism, and transitions of care pathways.

- A plain-language four-level categorization taxonomy should be used to help guide clinical services planning:

References

- regionaltraumasystems.pdf [Internet]. [cited 2024 Feb 29]. Available from: https://www.facs.org/media/sgue1q5x/regionaltraumasystems.pdf

- Kocher KE, Sklar DP, Mehrotra A, Tayal VS, Gausche-Hill M, Myles Riner R, et al. Categorization, designation, and regionalization of emergency care: definitions, a conceptual framework, and future challenges. Acad Emerg Med. 2010 Dec;17(12):1306–11.

- Carr BG. Emergency Department Categorization. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2007;14(4):381–2.

- Medicine I of. IOM Report: The Future of Emergency Care in the United States Health System. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2006;13(10):1081–5.

- Carr BG, Martinez R. Executive Summary—2010 Consensus Conference. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2010;17(12):1269–73.

- Sampalis JS, Denis R, Lavoie A, Fréchette P, Boukas S, Nikolis A, et al. Trauma care regionalization: a process-outcome evaluation. J Trauma. 1999 Apr;46(4):565–79; discussion 579-581.

- Brown AD, Naylor PWTP and CD. Regionalization Does Not Equal Integration. HealthcarePapers [Internet]. 2016 Jul 29 [cited 2024 Feb 29];16(1). Available from: https://www.longwoods.com/content/24765/healthcarepapers/regionalization-does-not-equal-integration

- Bergevin Y, Habib B, Elicksen-Jensen K, Samis S, Rochon J, Roy JLD and D. Transforming Regions into High-Performing Health Systems Toward the Triple Aim of Better Health, Better Care and Better Value for Canadians. HealthcarePapers [Internet]. 2016 Jul 29 [cited 2024 Feb 29];16(1). Available from: https://www.longwoods.com/content/24767/healthcarepapers/transforming-regions-into-high-performing-health-systems-toward-the-triple-aim-of-better-health-

- Martinez R, Carr B. Creating Integrated Networks Of Emergency Care: From Vision To Value. Health Affairs. 2013 Dec;32(12):2082–90.

- Vaughan L, Browne J. Reconfiguring emergency and acute services: time to pause and reflect. BMJ Qual Saf. 2023 Apr 1;32(4):185–8.

- Abu-Laban RB, Christenson J, Lindstrom RR, Lang E. Emergency care clinical networks. CJEM. 2022;24(6):574–7.

- Hansen K, Boyle A, Holroyd B, Phillips G, Benger J, Chartier LB, et al. Updated framework on quality and safety in emergency medicine. Emerg Med J. 2020 Jul;37(7):437–42.

- Daniels N. Just Health: Meeting Health Needs Fairly [Internet]. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2007 [cited 2024 Feb 29]. Available from: https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/just-health/1322AC95E8FEA51A978F200200A103A4

- Myers SR, Salhi RA, Lerner EB, Gilson R, Kraus A, Kelly JJ, et al. A pilot study describing access to emergency care in two states using a model emergency care categorization system. Acad Emerg Med. 2013 Sep;20(9):894–903.

- Benjamin P, Bryce R, Oyedokun T, Stempien J. Strength in the gap: A rapid review of principles and practices for urgent care centres. Healthc Manage Forum. 2023 Mar 1;36(2):101–6.

- NHS England » Urgent treatment centres – principles and standards [Internet]. [cited 2024 Feb 29]. Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/publication/urgent-treatment-centres-principles-and-standards/

- Urgent Care Centres – Calgary Zone Review and Recommendations. 2013;

- RUDi – RCCbc [Internet]. [cited 2024 Feb 29]. Available from: https://rccbc.ca/initiatives/rtvs/rudi/#

- baytek. Critical Care Services Ontario. [cited 2024 Feb 29]. Technology Assisted Remote Critical Care Services. Available from: https://criticalcareontario.ca/solutions/technology-assisted-remote-critical-care-services/

- Trekk – Translating Emergency Knowledge for Kids [Internet]. [cited 2024 Feb 29]. Available from: https://trekk.ca/topic/fever?tag_id=C001234

- Fleet R, Turgeon-Pelchat C, Smithman MA, Alami H, Fortin JP, Poitras J, et al. Improving delivery of care in rural emergency departments: a qualitative pilot study mobilizing health professionals, decision-makers and citizens in Baie-Saint-Paul and the Magdalen Islands, Québec, Canada. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020 Jan 29;20(1):62.

- ICES [Internet]. [cited 2024 Feb 29]. ICES | Development of a Consensus on Evidence-Based Quality of Care Indicators for Canadian Emergency Departments. Available from: https://www.ices.on.ca/publications/research-reports/development-of-a-consensus-on-evidence-based-quality-of-care-indicators-for-canadian-emergency-departments/

- Larsson S, Clawson J, Howard R. Value-Based Health Care at an Inflection Point: A Global Agenda for the Next Decade. Catalyst non-issue content [Internet]. 2023 Feb 24 [cited 2024 Feb 29];4(1). Available from: https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.22.0332

- NHS England » Transformation of urgent and emergency care: models of care and measurement [Internet]. [cited 2024 Feb 29]. Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/publication/transformation-of-urgent-and-emergency-care-models-of-care-and-measurement/

- The state of Urgent and Emergency Care and the question of the Clinical Review of Standards | From the president [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2024 Feb 29]. Available from: http://president.rcem.ac.uk/index.php/2022/02/01/the-state-of-urgent-and-emergency-care-and-the-question-of-the-clinical-review-of-standards/

- ACEM_QualityStandardsEDs_Report.pdf [Internet]. [cited 2024 Feb 29]. Available from: https://acem.org.au/getmedia/f4832c56-2b59-4654-815b-cdd1a66b27a8/ACEM_QualityStandardsEDs_Report

- Emergency Care BC [Internet]. [cited 2024 Feb 29]. Available from: https://emergencycarebc.ca/

- Purdy E, Forster G, Manlove H, McDonough L, Powell M, Wood K, et al. COVID-19 has heightened tensions between and exposed threats to core values of emergency medicine. CJEM. 2022;24(6):585–98.

- Shojania KG. What problems in health care quality should we target as the world burns around us. CMAJ. 2022 Feb 28;194(8):E311–2.

Chapter 4: Competencies, Certification and Teamwork (1)

| In a value-based health system, patient value becomes what evolutionary biologists call the ‘selection principle’ against which the contribution and performance of all institutions in the system, as well as the effectiveness of health-system reform initiatives, are assessed and evaluated. [1]. |

Introduction

Emergency medicine emerged as a specialty to improve outcomes for patients with acute illnesses and injuries. Over the past 50 years, emergency care systems have evolved to provide timely access to quality care. This is the overarching context in which we consider the future of competencies, certification, and teamwork in emergency care.

The Relationship Between Competencies and Clinical Services Planning

The breadth, depth, and maintenance of competencies for team members to provide care can be relative to the category of an ED (see Chapter 3). But the care provided by all staff, including physicians, should not fall below a minimum standard, otherwise it cannot be called an emergency department anymore.

Before we elaborate, it is important to understand power and responsibility in healthcare before we can improve or change the system. Who is responsible for assuring EM competencies are met? Who is recognized as having the legitimacy to certify those competencies, and make changes under the current governance structures? In Canada, provincial governments and their ministries establish and regulate EDs. This includes the governance and implementation of standards, competencies, and certification. In the current era of competence-based education, knowledge and expertise is currently determined by someone’s initial education and the competencies they’ve acquired.

Emergency medicine competencies for physicians are defined and certified by national colleges, including the Certificate of Added Competence (CAC) for EM conferred by the College of Family Physicians; and the Royal College of Physicians’ EM and Pediatric Emergency Medicine (PEM) fellowships. These colleges additionally support and accredit both educational and physician maintenance of proficiency programs. Health authorities and hospitals operationalise ED standards and professional behaviour through the process of granting and renewing individual physician privileges. Provincial Colleges of Physicians and Surgeons are mandated to protect the public and hold individual physicians accountable to minimum competencies and professional standards. Finally, though not a certifying or accrediting body, CAEP advocates for physicians working in EDs across Canada, and for the patients/populations they serve.

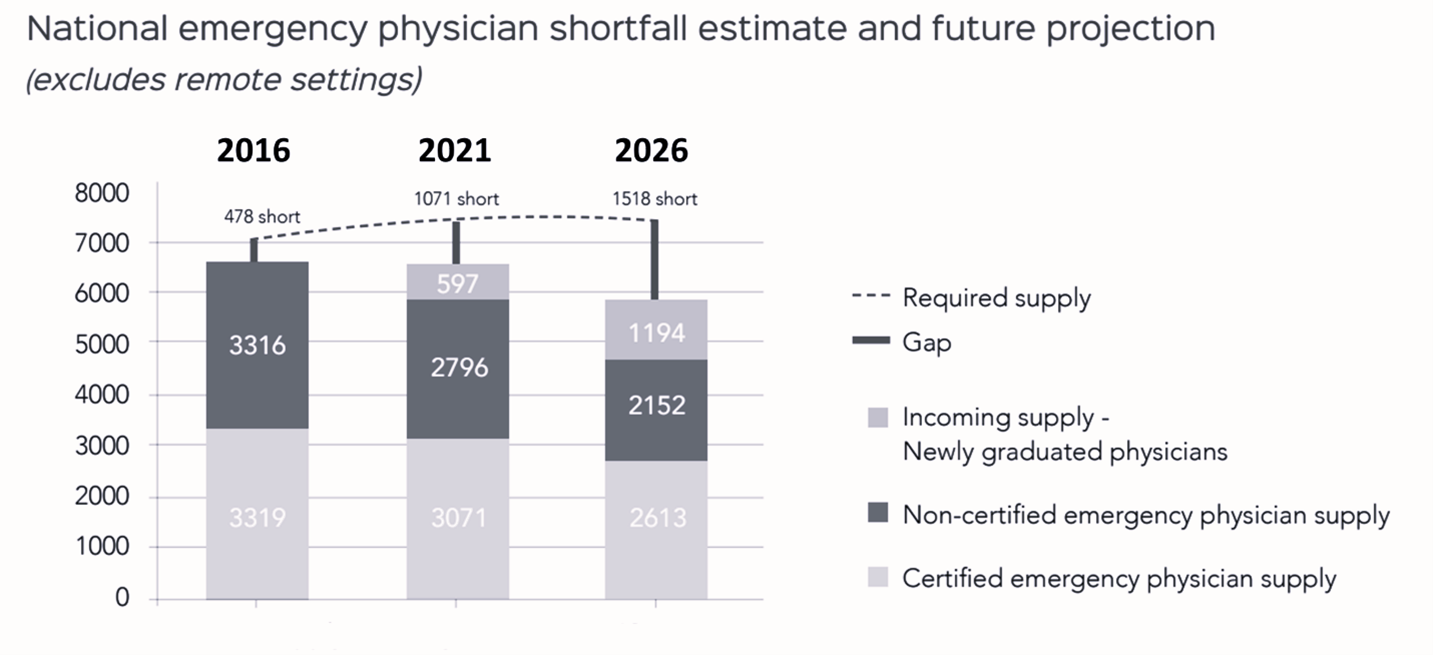

EM:POWER, and its proposed emergency physician resource planning model (Chapter 6), supports the 2016 Collaborative Working Group (CWG) report and recommendations that showed a large and growing shortfall of emergency physicians working in Canada’s EDs. (2) Based on a national survey, Figure 1 below shows the shortfall estimates that were calculated before the impacts of COVID-19. The pandemic resulted in greater burnout, increased retirement rates, reduced clinical shift loads for many who remained, and the reduction or elimination of ED coverage from the comprehensive practices of many family physicians. The coverage gaps in rural and remote settings were under-represented in this data, as was the population growth, so the current and projected gaps are likely substantially larger than those presented here.

Figure 12. shows the estimated mix, demand, and supply of physicians providing ED coverage in Canada from a base year in 2016, and then projected to 2021 and 2026. At the time, the finding was that the FTE (Full Time Equivalent) shortfall would rise from approximately 500 to 1000 and to 1500 by 2026. (2) This data counts physician numbers not full-time equivalents (FTEs), so if two doctors are only working a half-time shift, they only make up one FTE. The data does not adequately capture the potential for more part-time emergency physicians post-pandemic.

Figure 12. shows the estimated mix, demand, and supply of physicians providing ED coverage in Canada from a base year in 2016, and then projected to 2021 and 2026. At the time, the finding was that the FTE (Full Time Equivalent) shortfall would rise from approximately 500 to 1000 and to 1500 by 2026. (2) This data counts physician numbers not full-time equivalents (FTEs), so if two doctors are only working a half-time shift, they only make up one FTE. The data does not adequately capture the potential for more part-time emergency physicians post-pandemic.

Another key recommendation of the CWG report was for better alignment between the two main certification programs, with increased specific and meaningful collaboration needed between the CFPC and FRCP. Notably, the report did not recommend reducing the pathways to EM certification by eliminating one or merging the two programs together. The transition to competence-based education has allowed the two colleges to come together to clarify purpose, scope, and to work out how each can complement the other.

Through a systems lens there are benefits to having three pathways to EM certification in Canada (CFPC-EM, FRCP-EM, and FRCP-Peds EM): this makes the healthcare system more resilient though optionality. It also creates an element of safe redundancy and educational surge capacity in the EM training system. The three programs also offer a multitude of options for learners in terms of timing of entry, as well as intensity and duration of training, which additionally capitalizes on changing career plans.

Finally, the CFPC does certify that comprehensively-trained family physicians are qualified to work in small rural EDs without a certificate of added competence in EM. Instead, emergency competencies are attained during the Family Medicine residency. These are often supplemented by continuing medical education courses like Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS), Advanced Cardiac Life Support (ACLS), Pediatric Advanced Life Support (PALS), Point-of-Care Ultrasound (POCUS), and advanced airway management courses. Two other programs that increase the breadth and depth of EM competencies for family physicians who regularly work in an ED are the Supplementary Emergency Medicine Experience (SEME) program, developed at Mt Sinai in Toronto, (3) and the Nanaimo Emergency Education Program. (4) Both the Northern Ontario School of Medicine and Queen’s University School of Medicine also offer additional training for comprehensive rural generalists. Interestingly, one of the stated reasons for the previously proposed increase in the length (from two to three years) of the Family Medicine residency was to further supplement the growing body of knowledge, as well as the increasing number of competencies required for many aspects of a comprehensive family physician (FP) practice, including ED coverage. (5)

The Relationship Between Certification and Physician Resource Planning

Mathematical and modelling questions exist to plan future ED staffing both regionally and nationally. One question arises at a systems level when the goal is to provide optimal care and coverage for patients seeking care in Canada’s EDs: what is the ideal recommended mix/range of the variously certified emergency physicians, and comprehensively-trained family doctors with CFPC certification?

If we cannot differentiate practically, then we cannot count how many we have now and make intelligent recommendations about how many of each we need in the future to improve our system. Other questions include how do we optimize the scope of practice of other professionals? How do we improve our team approach to care? These are key considerations for a needs-based Health Human Resources model (see Chapter 6). Pragmatically, they are key considerations for system payors/planners and Post Graduate Medical Education Deans to consider when they appropriately adjust the number of residency positions required to meet the Canada’s future emergency care needs.

Forward-looking integrated health human resources (HHR) planning will focus on services planning at the system level AND optimizing teams at the site level, applying role clarity, team design, and collaborative practice. Certification (including practice eligibility routes) is essential at the system level for the future of EM care in Canada, but this does not minimize the importance of non-EM certified physicians who have contributed so much to the history and development of the emergency medicine field in the past. Many have been, and continue to be, key contributors in clinical practice, education, and leadership across the country.

EM:POWER endorses both the CAEP Definitions paper, (6) and the vision and mandate of the CAEP Rural, Remote, and Small Urban section, (7) both of which are relevant to these issues. These two documents are complementary rather than mutually exclusive as outlined below:

Emergency Medicine: is a field of medical practice (care of unexpected time-dependent illness and injury) defined by a unique body of knowledge. This means EM is not defined by the location of practice, but rather by a scope of competencies, as are other fields of medical practice. For instance, Family Medicine is also a field of medical practice defined by a unique body of knowledge. There is some overlap in competencies between these two fields of medical practice which makes the system more resilient.

Emergency Physician (when used as a noun): is a physician certified (or deemed practice-eligible by their respective colleges) in the practice of emergency medicine. Residency trained and certified FPs without CAC-EM certification in Canada also provide emergency care and may be particularly well-suited (but not limited) to practice in rural settings, as per the CFPC.

Emergency Department: taking the IFEM definition above one step further, the stratification and standards of Level 1,2,3,4 EDs are clarified in Chapter 3. At its core, an Emergency Department is structured and defined by its ability to provide acute care to all patients with unexpected and time-dependent illness and injury.

Canadians expect that an ED, by definition, can safely respond to the sickest patient that will arrive at its door, by ambulance, or by any other means. If it cannot, it should not be called an emergency department.

Certification in Emergency Medicine (either through the FRCP-EM, FRCP-Peds/EM or through the CFPC-CAC) strengthens the discipline of emergency medicine overall, and more importantly, improves the healthcare system’s pursuit of the Quintuple Aim. (8) CAEP/EM:POWER also supports the current situation that the CFPC has the jurisdiction to train and certify graduates to provide emergency care in rural and remote settings and recognizes that this is essential for the sustainability of the emergency care system in Canada.

Local and regional networks of emergency care must support physicians working in these locations through educational and competency maintenance opportunities (digital and experiential), shared/exchange workplace opportunities, and real-time peer-to-peer telemedicine connections as needed.

Provincial Emergency Care systems should be working towards requiring certified emergency physicians (or practice-eligible as defined by the respective colleges) to work in Level 1, 2, and 3 EDs. A comprehensively- trained family physician with emergency competencies is also certified by the CFPC to work in the ED and continues to play an essential role in staffing Level 4 emergency departments. Further discussion about developing and supporting this role, and the integration of all EDs into a single system with multiple access points are described in Chapter 6.

HHR Planning Must Follow Clinical Services Planning

Beyond physicians, providing effective emergency care at the bedside has always depended on interdisciplinary teams. Solutions to the current HHR gaps include training more emergency physicians, together with expansion of the team membership and evolution of the members’ scope of practice. Registered nurses, paramedics, social workers, discharge planning nurses, pharmacists, and many others can all play a vital role in the more-than-the-sum-of-its-parts ED unit. Specific emergency competencies for each should be clearly established, attained, certified (where appropriate) and maintained. All providers should work to the limits of their scope of practice.

When following good practice around adult learning and educational accreditation standards, scopes of practice can be specialized or expanded. An example of specialization is the emergence of geriatric emergency medicine (GEM) nurses to improve geriatric care in the ED. (9) An example of scope expansion is the use of paramedics within the ED who have been trained beyond their traditional scope of practice to suture, cast, splint, and assist with airway management, procedural sedation, and analgesia. (10)

Three questions should be asked with the addition of any new team member, or proposed expansion of a skillset in the ED, bearing in mind that the issue isn’t should we add a new member to the team; the question should be what unmet patient needs are there, and how do we best address them?

- What unmet role/function on the team is being addressed?

- How does this new/expanded skill contribute to improving patient outcomes?

- What are the potential positive and negative unintended consequences?

Nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs) are part of ED teams in some locations and fill different roles across the country. NPs are considered independent practitioners under most provincial legislation. In contrast, PAs are not independent practitioners, but rather are considered ‘physician extenders.’ In Canada, currently all NP programs are based on a 1–2-year primary care competencies curriculum following RN training. Some graduates receive additional disease-specific training after completing the NP program.

Currently, there are no NP programs in Canada designed specifically around emergency care skills and procedures. Most PAs are certified in some emergency care competencies. (Many were originally trained rigorously through the military although this is no longer our primary source). A more detailed description of the required skills, strengths/weaknesses, and potential roles in the ED for Canadian settings has been published by the Centre for Health Services and Policy Research at the University of British Columbia. (11)(12)

The evidence around the utility and benefits of NPs and PAs in the ED paints a mixed picture. An early systematic review suggested that the addition of NPs may result in the reduction of the wait times for low acuity patients, and in some cases, improved patient satisfaction. (13,14) However, a more recent three-year study in the US by the Federal Bureau of Economics comparing NPs to EPs practicing in the emergency department showed that the NPs ordered more tests, had worse outcomes, and incurred increased costs to the system overall. (15)(16) Clearly, the potential roles PAs or NPs could fill should be complementary to the ED’s team function—rather than in parallel or even as a replacement for an emergency physician. Optimizing ED care provided by NPs and PAs will require an intentional approach to roles, responsibilities, and team-building in site-specific contexts.

In a more rural setting, co-locating some primary care capacity provided by NPs may make sense if better access to primary care is unavailable elsewhere outside the ED, though again, the evidence is mixed on this. (17) On the other hand, busy urban EDs may benefit from the skills and procedures that a physician extender or PA could provide by maintaining the flow of CTAS 3,4 and 5 patients (where expanded scope RNs or paramedics can’t be trained to fill similar roles).

Regardless, different team members in different contexts can all bring value when the focus is on high-functioning teams in service of patient outcomes. Attaining, and maintaining individual and team competencies are essential to improve the future of emergency care in Canada. But effective teams are more than a sum of their competencies, or certifications; their performance depends on much more than that. Teams work best when they have a shared purpose, coordinated roles/contributions, and common core values.

Core Values

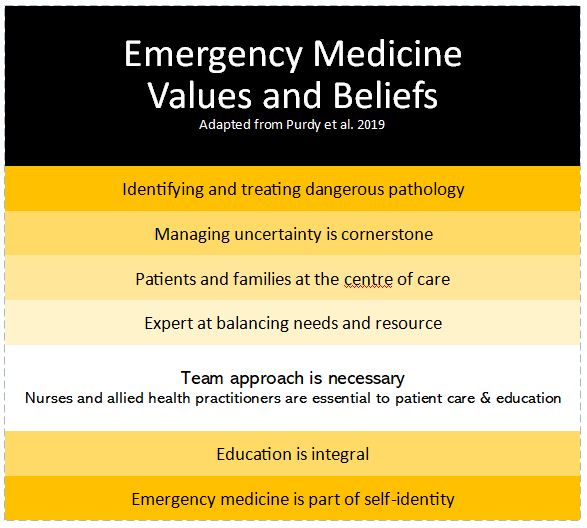

Emergency medicine values and principles drive behaviour in professional practice, leading to a sense of purpose and fulfillment. (18) Finding meaning in our work, otherwise known as being internally motivated, influences our actions more than external motivators, the proverbial sticks and carrots. (19) We are committed to the patients and populations we serve. Explicitly expressing, resolving, and refining these core values are important for developing our professional identity; doing so builds coherent and collaborative teams who work together effectively as we create the future of emergency care.

Unfortunately, a mismatch or incongruence of values can also be a source of moral injury and burnout. System leaders and policymakers must understand how their decisions (or non-decisions) indirectly impact patient care. Competencies define our education in emergency medicine, and professional identity development starts with core values (see Figure 2) that evolve with practice and experience.

Figure 11. Refined Emergency Medicine Value framework adapted from Purdy et al (18)

Two other concepts that are implicit in the values identified in Figure 13 are situational awareness and system savviness. These concepts are embodied in provider actions that address patient and family needs, balance a rational approach to resource stewardship, and help ED teams provide complicated and time-pressured clinical care—as well as transitions of care—to other services or hospitals.

Teams (and Teams of Teams)

|

Emergency care is a team sport, and emergency teams are inherently dynamic. No two shifts are the same. No two hours are the same. The team must act immediately in response to unscheduled and often unanticipated events; it must learn to read, react, respond, recover, and get ready again, together.

In his recent book “The Power of Teamwork: How we can all Work Better Together,” veteran emergency physician, Brian Goldman (20) speaks to the critical difference between a group and a team. Individuals with different skills and backgrounds can exist together in a group; but “to be a team, these individuals must be interdependent in terms of knowledge, abilities, and the materials they work with. And they must work together to achieve a shared goal.” (20) It is the shared goal, or shared purpose, and shared mental models that bring coherence and effectiveness to a team. (21,22)

Crisis Resource Management is a concept from aviation safety that has been modified for use in the healthcare setting and has been shown to significantly reduce error. (23) It is often taught to medical learners in simulation/resuscitation training, but the principles can be applied in broader contexts.

These principles include:

- Knowing your environment

- Knowing your goal

- Knowing your role, shared workloads

- Anticipate and share information, and

- Have shared mental models, leadership and followership, and clear communication loops.

The Toyota Flow System (24) has three pillars: complex thinking, distributed governance, and team science. These pillars show that creating and nurturing teams is an essential part of any organization—and these lessons have relevance in emergency care. Some of these principles are like those found in crisis resource management, and include:

- Goal/purpose identification

- Training and learning together

- Situational awareness, and

- Human-centred design.

Human-centred design is a particularly important principle that stresses the importance of involving all stakeholders in the design of teams that are best able to improve value-based care in healthcare systems. In this context, patients, communities, providers, administrators, and payors should be part of the design process.

It is not just care in the ED; all healthcare is now (or should be) provided by multi-disciplinary teams. The future of emergency care will be improved in a Team of Teams environment. (25) The concept of organizing complex endeavours with a Team of Teams approach stems from the observation that rigid, top-down, command and control hierarchies are not a good fit for our increasingly turbulent and uncertain world. These old approaches lead to fragmentation and dis-integration, something that has been painfully obvious in healthcare.

Team adaptation and effectiveness must be valued more (or at least balanced with) efficiency. To that end, the principles of a Team of Teams approach include shared consciousness and empowered execution, following the idea that neurons that fire together, wire together. Shared consciousness in this context means there is trust amongst and between teams because of a shared purpose (value in healthcare), and radical transparency around information flows and resource allocation decisions. Once shared consciousness is achieved, decisive action with a sense of agency can be implemented, which means empowering front-line teams to do the right thing in service of the shared goal. This drives bottom-up innovation and system change.

Creating High Functioning Teams (Not Just Expanding Groups)

Team function within the emergency department can have a significant impact on provider wellness (or burnout), provider performance, patient flow, and ultimately patient outcomes. It is essential for achieving the Quintuple Aim. Emergency care team function is impacted by factors at various levels: system, organization, department, team, and individual. A recent response to the access block in some Canadian provinces has been to reactively alter care delivery models to include and/or expand the scope of other medical providers in the delivery of “emergency care,” often with politically-expedient timelines, rather than value-based considerations. (1) This might expand emergency department groups, but is it creating high-functioning emergency department teams? Every so-called innovation in care delivery models must be evaluated for its impact on team function and patient outcomes. This is key.

While the drive to maximize the scope of practice of medical providers can make intuitive sense in a resource-limited environment, it is critical to be intentional around our strategies. Appropriateness and effectiveness in the emergency department must be carefully considered. Nurses, NPs, paramedics, and physician assistants have inter-profession and intra-profession variations in clinical scope and practice independence. Emergency physicians have a breadth and depth of knowledge, training, skills, and system savviness, which makes them ideally suited to lead teams of emergency care providers. We must not equate independence (or lack thereof) with having the competencies to practice in the ED, or with being an ideal fit for team development. Rather, we need to consider the context (ED category, department size, remoteness index, resource deficiencies/metrics) and plan explicitly around whether additional members are simply enlarging the group or improving the team.

- What is the problem we’re solving?

- How does this improve the Quintuple Aim?

- What are the alternatives?

- What are the likely/potential unintended consequences?

Bottom line: emergency department function and quality of care is much more complex than access alone, and access without integration and teamwork can negatively impact performance and outcomes. Improving EDs with more and different providers needs to be intentional; it needs to be about expanding our team and not simply enlarging our group. (26,27) The implications of how optimizing the size and makeup of teams in the ED can impact HHR planning will be discussed in Chapter 6.

Community of Practice (CoP)

At a broader regional, provincial, and even national level, the concept of communities of practice is also important to the future of EM Canada. “A community of practice . . . is a group of people who share a common concern, a set of problems, or an interest in a topic and who come together to fulfill both individual and group goals.” (28) In other words, the CoP concept helps us to emphasize developing relationships in service of a shared purpose, (29) which is vital to improving emergency care in Canada.

This provides another mental model for breaking down silos and untangling turf wars. It keeps the eyes on the prize, which in this case is population outcomes, patient experience, provider wellness, equity, and cost-effectiveness.

In practical terms, a Community of Practice can be created with a larger, more academically-oriented ED, adopting a smaller sister site(s) with shared recruiting and scheduling. It can also manifest as mentoring relationships through hub-and-spoke related EDs, and/or practice support programs, regional interprofessional simulation programs, multi-disciplinary journal clubs, provincial emergency care clinical networks, and even national grand rounds.

Conclusion

Emergency Medicine is defined by a unique and growing body of knowledge which comes with a unique and growing spectrum of competencies. The future of Canada’s emergency care will be optimized by improving, strengthening and maintaining the competence-based education and ecosystem that serves our country well. The patients and populations we serve will also benefit from the intentional development of teams, and empowering communities of practice around shared goals.

Recommendations for Competencies, Certification and Teamwork

- ECCNs should ensure that to work in an ED, attaining and maintaining individual and team emergency care competencies is required. The resources and opportunities necessary to meet this expectation should be funded and/or supported by the MoH/HA.

- The CAEP 2020 vision statement should be updated, nuanced, and re-endorsed to reflect distinctions between Level 1-4 EDs in Canadian urban and rural centres. All emergency physicians entering practice in Level 1 and Level 2 EDs should be certified in emergency medicine. Coverage in Level 4 EDs can be provided by comprehensively-trained family physicians with the necessary EM competencies. Level 3 EDs should work towards coverage by certified emergency physicians over the next decade. Given the shortage of emergency physicians in Canada, concerted efforts to increase EM residency training positions and prepare practice-eligible certification candidates will be crucial in attaining this goal.

- CAEP and emergency care leaders in nursing and paramedicine should advocate for the funding/support necessary for nurses and paramedics to attain and maintain emergency care competencies. They should also encourage all providers to work to their full scope of practice and enable expanded scopes where needed (e.g., geriatric critical care, etc.).

- ECCNs should establish and support team-based care, creating complementary roles and responsibilities in the service of patient needs.

- Team science should be used in the design and evaluation of team performance in the ED.

- Mid-level providers such as NPs, PAs, Doctors of Pharmacy (Pharm Ds) etc. should attain/maintain emergency care competencies and be added to the ED staff when and where they complement the team approach to improving patient care.

- Inter-disciplinary simulation should be used extensively in the training and maintenance of competence of ED teams. Simulation resources and programs should be funded and supported by ministries of health and health authorities.

- Emergency physicians should provide a leadership role in a team approach to care in an ED.

- A Community of Practice (muti-disciplinary, shared goal, common interests) approach to improving emergency care across silos, sectors, and systems should be intentionally developed and supported.

References

- Larsson S, Clawson J, Howard R. Value-Based Health Care at an Inflection Point: A Global Agenda for the Next Decade. Catalyst non-issue content [Internet]. 2023 Feb 24 [cited 2024 Feb 29];4(1). Available from: https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.22.0332

- Collaborative Working Group on the Future of Emergency Medicine in Canada. Emergency Medicine Training and Practice in Canada: Celebrating the Past and Evolving for the Future. 2016;

- SEME [Internet]. [cited 2024 Feb 29]. Rural ER Fellowship | SEME – Supplemental Emergency Medicine Experience. Available from: https://www.semedfcm.com

- NEEPDocs – Nanaimo Emergency Education Program [Internet]. [cited 2024 Feb 29]. Available from: https://neepdocs.ca/

- Fowler N, Oandasan I, Wyman R. Preparing Our Future Family Physicians an educational prescription for strengthening health care in changing times.

- McEwen J, Borreman S, Caudle J, Chan T, Chochinov A, Christenson J, et al. Position Statement on Emergency Medicine Definitions from the Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians. CJEM. 2018 Jul;20(4):501–6.

- Rural, Remote and Small Urban Section – CAEP [Internet]. [cited 2024 Feb 29]. Available from: https://caep.ca/em-community/rural-and-small-urban-section/

- Sutherland K, Leatherman S. Does certification improve medical standards? BMJ. 2006 Aug 26;333(7565):439–41.

- Leaker H, Holroyd-Leduc JM. The Impact of Geriatric Emergency Management Nurses on the Care of Frail Older Patients in the Emergency Department: a Systematic Review. Canadian Geriatrics Journal. 2020 Sep 1;23(3):230–6.

- Clarke BJ, Campbell SG, Froese P, Mann K. A description of a unique paramedic role in a Canadian emergency department. International Paramedic Practice. 2019 Jun 2;9(2):28–33.

- Utilization-of-Nurse-Practitioners-and-Physician-Assistants.pdf [Internet]. [cited 2024 Feb 29]. Available from: https://albertanps.com/downloads/Utilization-of-Nurse-Practitioners-and-Physician-Assistants.pdf

- guidelines-reg-the-role-of-physician-assistants-and-nurse-practitioners-in-the-ed.pdf [Internet]. [cited 2024 Feb 29]. Available from: https://www.acep.org/siteassets/new-pdfs/policy-statements/guidelines-reg-the-role-of-physician-assistants-and-nurse-practitioners-in-the-ed.pdf

- Carter AJE, Chochinov AH. A systematic review of the impact of nurse practitioners on cost, quality of care, satisfaction and wait times in the emergency department. CJEM. 2007 Jul;9(4):286–95.

- Drummond A. Nurse practitioners in Canadian emergency departments: An idea worthy of attention or diverting our attention? Canadian Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2007 Jul;9(4):297–9.

- Chan J David C, Chen Y. The Productivity of Professions: Evidence from the Emergency Department [Internet]. National Bureau of Economic Research; 2022 [cited 2024 Feb 29]. (Working Paper Series). Available from: https://www.nber.org/papers/w30608

- American Medical Association [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2024 Feb 29]. 3-year study of NPs in the ED: Worse outcomes, higher costs. Available from: https://www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/scope-practice/3-year-study-nps-ed-worse-outcomes-higher-costs

- Ramlakhan S, Mason S, O’Keeffe C, Ramtahal A, Ablard S. Primary care services located with EDs: a review of effectiveness. Emerg Med J. 2016 Jul 1;33(7):495–503.

- Purdy E, Forster G, Manlove H, McDonough L, Powell M, Wood K, et al. COVID-19 has heightened tensions between and exposed threats to core values of emergency medicine. CJEM. 2022;24(6):585–98.

- Drive | Daniel H. Pink [Internet]. Daniel H. Pink | The official site of author Daniel Pink. 2012 [cited 2024 Feb 29]. Available from: https://www.danpink.com/books/drive/

- HarperCollins Canada [Internet]. [cited 2024 Feb 29]. The Power of Teamwork – Brian Goldman – Hardcover. Available from: https://www.harpercollins.ca/9781443463997/the-power-of-teamwork/

- Rosen MA, DiazGranados D, Dietz AS, Benishek LE, Thompson D, Pronovost PJ, et al. Teamwork in Healthcare: Key Discoveries Enabling Safer, High-Quality Care. Am Psychol. 2018;73(4):433–50.

- Nancarrow SA, Booth A, Ariss S, Smith T, Enderby P, Roots A. Ten principles of good interdisciplinary team work. Hum Resour Health. 2013 May 10;11:19.

- Optimizing Crisis Resource Management to Improve Patient Safety and Team Performance–A Handbook for Acute Care Health Professionals. 2017 Aug;65(1):139.

- InfoQ [Internet]. [cited 2024 Feb 29]. The Flow System: Getting Fast Customer Feedback and Managing Flow. Available from: https://www.infoq.com/articles/flow-system-customer-feedback/

- Penguin Random House Canada [Internet]. [cited 2024 Feb 29]. Team of Teams by General Stanley McChrystal, Tantum Collins, David Silverman, and Chris Fussell. Available from: https://www.penguinrandomhouse.ca/books/317066/team-of-teams-by-general-stanley-mcchrystal-tantum-collins-david-silverman-and-chris-fussell/9781591847489

- Fernandez R, Kozlowski SWJ, Shapiro MJ, Salas E. Toward a Definition of Teamwork in Emergency Medicine. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2008;15(11):1104–12.

- Filho E. Team Dynamics Theory: Nomological network among cohesion, team mental models, coordination, and collective efficacy. Sport Sci Health. 2019 Apr 1;15(1):1–20.

- What is a community of practice? [Internet]. Community of Practice. [cited 2024 Feb 29]. Available from: https://www.communityofpractice.ca/background/what-is-a-community-of-practice/

- Research Impact Canada [Internet]. [cited 2024 Feb 29]. Community of Practice – Everything you Need to Know! Available from: https://researchimpact.ca/resources/community-of-practice-everything-you-need-to-know/

Chapter 5: System Integration

| “Healthcare remains disjointed, with poor coordination and alignment within and across the various professions, acute and chronic care institutions and community care. Lack of integration is partly understandable where there is a multitude of payers (e.g., public insurance, private insurance, out-of-pocket spending). That services that are solely publicly funded are still arranged in stovepipes has been harder for the Panel to comprehend.”

Unleashing Innovation, Report of the Federal Advisory Panel on Healthcare Innovation. [1] |

Integration has been identified as part of the solution to the current siloing and unsustainability of our fragmented healthcare delivery system in Canada. (1,2) An integrated model of care can be defined as “interprofessional teams of providers collaborating to provide a coordinated continuum of services to an individual supported by information technologies that link providers and settings.” (3)

In its report, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CHIR) identified 10 core principles for the successful integration of health systems. (3) They are:

- Comprehensive services across the core continuum

- Patient focus (value-based decision making)

- Geographic coverage and rostering

- Standardized care delivery through interprofessional teams

- Performance management (accountability)

- Shared information systems

- Physician integration

- Organizational culture and leadership (that support all the above)

- Governance structures (that support all the above)

- Financial management (that supports all the above).

The federal report on innovation in healthcare (Unleashing Innovation: Excellent Healthcare for Canada) suggests that integration itself should be seen as an innovation in systems (4). While recommendations on how to achieve this at the broader system level are discussed there, our focus emphasizes the potential opportunities of emergency care-related integration. Emergency medicine sits at the interface of many aspects of healthcare: out-of-hospital/in-hospital, primary care/secondary and tertiary care, acute care/chronic care, and hospital care/home care, etc. As a result, it has the power to catalyze change towards a more integrated and better-functioning future.

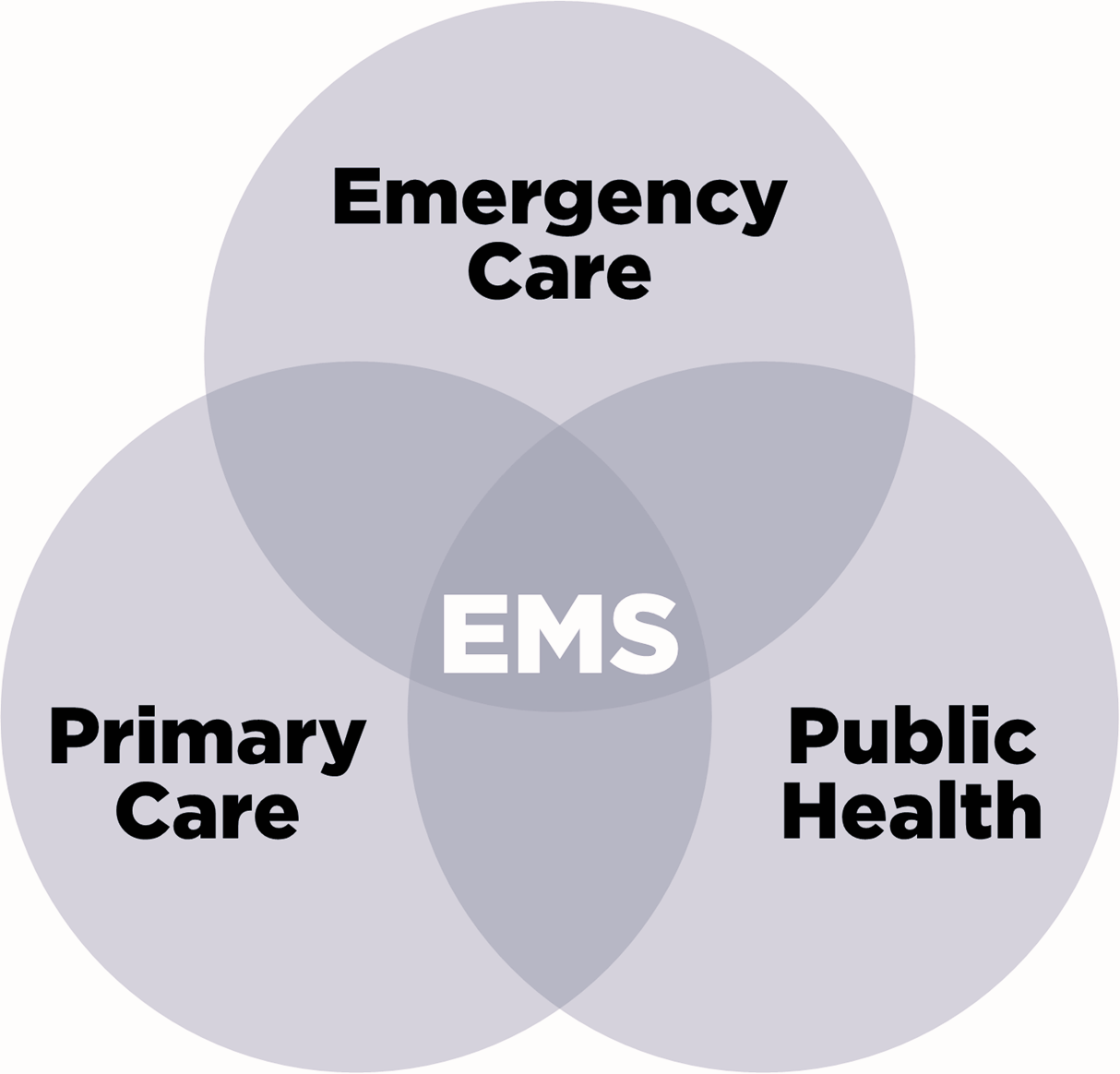

Networks are defined not by their nodes, but by their connections. How patients transition through their care journey is one example. Links exist between primary care (including home and continuing care), emergency departments (including network-integrated urgent treatment centres and virtual emergency care), and public health. Emergency medical services (EMS) play a coordinating role through its dispatch centre, and a connective and supportive role through its 911 transportation service, together with the integration potential of its mobile health services. (5–7)

Integration with Primary Care and Public Health

For many years there have been multiple calls and attempts to reform primary care in Canada. (8) Our colleagues in Family Medicine currently share our concerns and motivations for change in the crisis we face (9). Perhaps a one-size-fits-all approach to primary care reform is neither feasible nor wise, but there seems to be a growing consensus around the importance of the healthcare home, having a multi-disciplinary, regionally rostered, family health team (10)(11)(12) for everybody. Specific governance, policy, accountability, and physician funding obstacles to implementing such a network are discussed elsewhere, and we endorse those recommendations. (4)(13)(14)

The healthcare home model, combined with improved operational linkages with EDs, means transitions of clinical care become more coordinated and accountable, with more adaptive and dependable mechanisms for dealing with new challenges that arise. Standardized communications methods and tools can be implemented when patients are referred to the ED for an assessment or specific treatment. Universal Electronic Patient Care Records (ePCR) allow for shared knowledge on past medical history, recent tests and investigations, current medications, alerts and allergies, and goals of care. Likewise, improved transitions should be developed for the ED to communicate clinical follow-up with a patient’s own healthcare home team.

Finally, public health is being recognized as essential for a safe and effective healthcare system. (15) Its three core objectives are:

- Health promotion and chronic disease mitigation

- Infection disease prevention and control, and

- Health Security, including emergency preparedness and response as well as biosafety and biosecurity.

Figure 12. The overlap of Emergency Care, Primary Care, and Public Health services, Emergency Medical Services (EMS) can play an important role in coordinating and connecting care across all three areas.

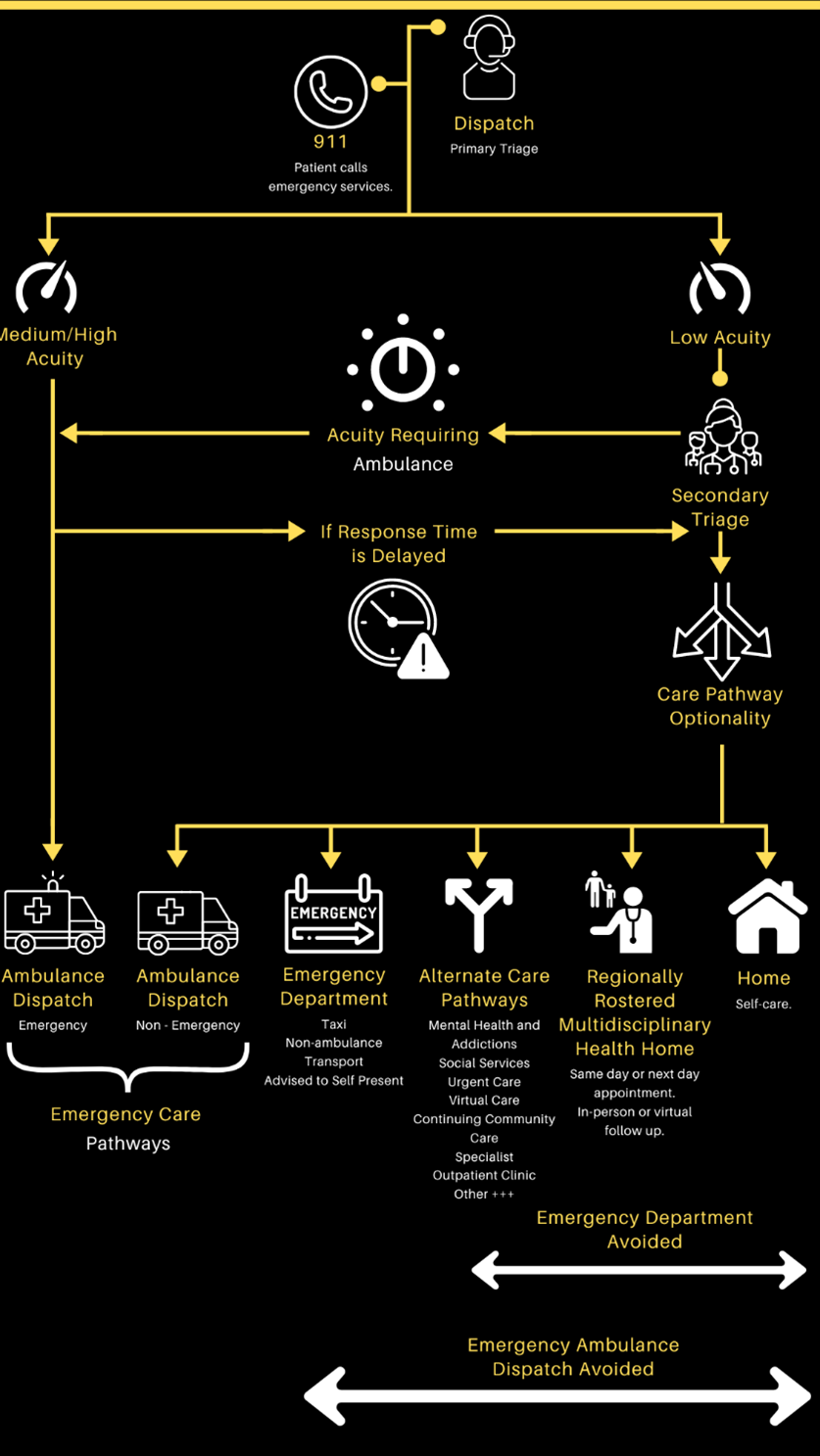

Integration With Emergency Medical Services (EMS)

Emergency medical services are now recognized as a subspecialty in the US, and an Area of Focused Competence by Canada’s Royal College. In 2006 the EMS Chiefs of Canada articulated an important vision for the future which moved the service from a “you call, we haul, that’s all” model, to a collaborative, integrated mobile health service partner. (16) Many jurisdictions have gone forward with those plans, and with Canadian healthcare systems in such crisis, EMS can play a major integrating role between out-of-hospital and in-hospital care. (17)

For example, the EMS central dispatch can become a Care Coordination Centre. In an integrated healthcare system, virtual care is not an end unto itself, but rather a means to an end. A functional model can be established that improves access, quality, coordination, and continuity of care, with virtual triage (risk stratification) and coordination (pathway navigation). (18)

However, there must be optionality in the care pathways for this care delivery model to work, so that “the right patients, can receive the right care, in the right place and/or through the right medium.” The ED should not be used as the sorting mechanism for non-emergent hospital-based services. (19) Alternative pathways other than the ED must be developed with easy and consistent access for potentially avoidable ED visits such as urgent, but not emergent diagnostic imaging and lab tests; specialist consultation; schedulable procedures (transfusion, pleurocentesis, feeding tube placements, etc.); and non-emergent post-operative concerns.

The concept of emergency physician as the “availabilist” (20) and the potential synergies with EMS-mobile integrated health solutions is gaining traction. To be clear however, any program development in this area should only occur after appropriate staffing is assured for the physical EDs in the system, and when primary care and specialist care services are accountable for their obligations to meet their own patient’s needs. Emergency care systems cannot be seen as the universal contingency plan for unmet needs in the rest of the system. Definitions and standards will also become even more important to assure integration and value, in addition to avoiding the exploitation of low-value retail medicine clinics, (21) or more fragmentation with unconnected, transactional, and low-quality virtual care options.

Multi-option EMS (22) is an idea that has been around for a while, and perhaps its time has come. An evidence-based (or at least rational consensus-based) approach to ambulance trip destination alternatives for some low-acuity patients could be thought of as Choosing Wisely EMS. Over 25 years ago the concept of multi-option EMS described three triage decision points for unique pathways to be developed:

- First, the 911 call taker (is an ambulance even needed or would a family physician appointment be better?)

- Second, when the paramedics arrive (is transport necessary, if so, by what crew/vehicle type and where to?) and

- Third, on arrival at the destination (with more time and information, is the ED still the best destination? (Would an urgent treatment centre or same day/next day appointment at the patient’s primary care home be a better alternative?)

Figure 13. How the central dispatch can play a coordinating role in multi-option EMS.

Reducing the number of low-acuity ambulance arrivals—or low-acuity walk-ins for that matter—will have minimal impact on hospital access block. It will not make a difference to the ED’s fixed costs (staffing, equipment, overhead, etc.) and may only have a minimal impact on the very low marginal costs. (23) It should, however, reduce the transport and off-load unavailability time of ambulances, and free up more units to be ready for the next 911 call; the impact of that alone could justify multi-option EMS. It may also improve patient experience and reduce paramedic burnout.

This report strongly recommends validated prospective field triage and risk stratification tools for a paramedic crew on-scene, with backup from an experienced online emergency physician, to decide in real time where they should transport their patient. For example, if ten 58-year-old men with cardiac risk factors all call an ambulance for their chest pain and mild shortness of breath, and after their ED visit, five of them turn out to be diagnosed with an FPSC (family practice sensitive condition), (24) does that mean that the ambulance service should transport half of their chest pain patients to a walk-in clinic? Of course not! Prospective decision-making and risk stratification in uncertainty cannot be evaluated retrospectively by outcomes; (25) they must be judged by the decisions made with the information available at the time.

Emergency physicians have long known that over-triage is a resource use issue, and under-triage is a patient outcome issue. No field or virtual care triage can ever be perfect; (26) sensitivity varies inversely with specificity. As we develop these trip destination options and pathways, the following questions arise:

- What level of risk is acceptable for the patients and populations we serve?

- How do we mitigate the inevitable under-triage?

- And who bears the medicolegal burden of that risk in such a system?