Section Editor: Grant Innes

Chapter 7

Access Block and Accountability Failure

Overview

Canada performs poorly relative to other wealthy countries in terms of access to primary care, specialists, elective surgery, and imaging. Canadians also face excessive delays to hospital and long-term care (LTC). Queues are ubiquitous, and these create significant health system dysfunction. Our country has the highest rate of ED use in the First World, and ED visits are rising rapidly, usually because the emergency department is the only place patients can get care when they need it.

When patient demand on a health program outstrips apparent care supply, the obvious solution is to block inflow and create a queue. Blocking access is a default response and primary coping mechanism for most programs; it is the opposite of a solution but delivers substantial rewards. Workload is controlled; waiting patients are out of sight and out of mind; staff stress is relieved and budgetary challenges are mitigated. Care shortfalls become someone else’s problem, and programs are protected from evolutionary stressors that would otherwise mandate innovation and improvement.

Care delays in any program have a domino effect, compromising other components of an interdependent system. Alternate Level of Care patients (ALC) who are blocked in hospitals compromise acute care access. Inpatients blocked in emergency departments (EDs) compromise emergency access. ED congestion causes ambulance offload delays that compromise community prehospital care response. The wrong patient in the wrong place on a large scale generates inefficiency, system cost, and adverse patient outcomes.

An accountability framework will not by itself improve access, but its absence is a recipe for failure.

A primary root cause of widespread healthcare dysfunction is unclear accountability, the system-level failure to define patient care expectations and a lack of planning to address care gaps. Without an accountability framework, any performance is acceptable. If no person or program is expected to solve specific access blocks, no one solves them. A critical priority for health system improvement is the development of an accountability framework. This would define accountability, clarify accountability zones (i.e., what program is responsible for what patients) and specify relevant performance targets. Core program accountabilities are to provide timely access to care; budget, space and nursing care for program patients; and contingency plans for managing surges and queues.

An accountability framework will not by itself improve access, but its absence is a recipe for failure. Clarifying program expectations will focus people on problems they have not yet had to address. Accountability is the evolutionary stressor required to drive beneficial system change. Key accountability themes include the importance of queue management plans, the concept of ethically allocating limited care resources based on patient need and likely benefit, together with limiting the tendency of programs to manage demand challenges by blocking access.

Access Block and Accountability Failure

Accessibility is a core tenet of the Canada Health Act, but our system performs poorly. [1-3] Canadians have the highest rate of emergency department (ED) use when compared with 11 other affluent countries. [4] Visits are rising rapidly, usually because the emergency department is the only place patients can get care when they need it. [5,6] Our country is next to last among OECD countries for access to primary care. Many Canadians cannot get a family doctor, and those who have one can rarely get same day, next-day, or after-hours appointments. Canada also performs poorly in terms of waits for specialists, elective surgery, and advanced imaging, which results in delayed diagnosis and care.

Poor system integration, [7,8] capacity shortfalls, staffing crisis, process inefficiency, population-capacity misalignment, and care maldistribution are contributing factors, [9] but critical root causes that must be addressed include the absence of a patient care accountability framework and a related lack of planning to address care gaps. [10-12]

Program Care

Programs are functional units in the healthcare system [10,11]. The term program usually refers to population level programs like primary, acute, or long-term care, but it can also refer to facility-level departments like pediatrics or critical care. Programs are staffed, equipped, and structured for the work they do. EDs are designed and staffed to diagnose and treat acute injury or illness over minutes to hours; surgical programs manage surgical conditions over days to weeks, and rehabilitation programs optimize long-term functional recovery. Acute care hospital wards do not provide excellent rehabilitation services, and EDs do not offer high-quality preventative healthcare. The best patient outcomes and system efficiencies occur when patients receive timely care from the right providers in the right place. This appropriateness is a core goal for all health systems. [9,12]

Wrong Care in the Wrong Place Hurts Patients and Systems

The best patient outcomes and system efficiencies occur when patients receive timely care from the right providers in the right place.

Care delays cause morbidity and mortality. [9,13-25] Older patients blocked in acute hospital wards do not receive necessary rehabilitation, with the risk of cognitive decline and deconditioning that lead to institutionalization rather than independence. [26,27]

Hospital inpatients deteriorate if held for hours or days on hard narrow ED stretchers in crowded noisy rooms without privacy, bathroom access, or sleep, and where the lights never go out. [22,23] Acutely ill arrivals with strokes and miscarriages languish or deteriorate in ED waiting rooms when stretchers are blocked by inpatients. [26] Queuing, care delays and wait times all reflect access block, which is the biggest problem for Canadians seeking care. [1,2,28]

Wrong care in the wrong place also causes widespread system dysfunction. [11,28-31] Failure in any program has a domino effect, compromising other components of an interdependent system. [11,17,32] Delays to long-term care mean patients who should be in the community block hospital beds, instead compromise acute care access. [33] Blocked hospital beds lead to blocked ED stretchers, compromising emergency care. Ambulance crews unable to offload patients at congested EDs cannot respond to emergencies in the community. [32] At every level, access block compromises upstream programs, patient outcomes, system efficiency and costs. [34]

Access Block: Problem or Solution?

When demand outstrips supply and programs are unable to provide care to waiting patients, the obvious solution is to block inflow and create a queue. This is a default coping mechanism for most programs, including emergency departments. [28,33, 35,36] It is the opposite of a solution, but delivers huge rewards. Workload is controlled, waiting patients are out of sight and out of mind, staff stress is relieved, and budgetary challenges mitigated. Care shortfalls become someone else’s problem, and the program is protected from evolutionary stressors that would otherwise mandate innovation and improvement. [11]

|

Blocking access prevents patients from getting the care they need, shifts care demands away from programs able to provide a service to programs that can’t, and displaces the consequences of access failure to other parts of the system. If management by blocking access is acceptable, and underlying causes are disconnected from consequences, leaders who are able to correct root problems are protected from doing so, while affected leaders are incapable of solving them, even if they’re the most motivated. [11] This is a recipe for ongoing system failure.

Accountability Frameworks

It is often unclear who is expected to come up with a solution when patients cannot access necessary care. If accountability is undefined and no one is expected to solve access blocks, no one solves them. Accountability is the evolutionary stressor needed to drive necessary system change. [11] An accountability framework links programs to expectations, clarifying that all programs are accountable for their target populations. [12,31,37] The framework includes:

- A definition of accountability

- Conceptual accountability zones, and

- Access-related performance targets.

It forces people and programs to ask: How would you change your care systems if blocking access were not an option?

Accountability Zones

Accountability zones clarify who is responsible for which patients, and where we look for access solutions (Table 3). [11,12] Logically, the service best able to address patient needs should provide care. If patients face surgical delays, accountability falls to the surgical program. Surgery has operating rooms and surgeons, and no other program can reduce surgical waits. Primary care programs are accountable for patients who need primary care. Emergency Medical Services (EMS) are accountable for patients requiring prehospital care, and EDs are accountable for all patients who arrive at their department. Hospital-based medical programs are accountable for patients who have been referred for inpatient care, and community long-term care (LTC) programs are accountable for patients who do not require hospitalization but cannot function independently in the community. The right program is usually obvious, but accountability is sometimes shared.

Health ministries also have accountability (see discussion below), and patients should be accountable for how they use the system, but the latter is a complex issue that depends, among other things, on the availability of non-ED care options, and definitions of appropriate ED use.

| Program | Accountability | Program Boundaries |

| Primary care | Patients who need primary and preventive care. | Encompasses most of the population, although the need is not immediate. |

| EMS (Emergency Medical Services) | Patients requiring

prehospital care. |

Begins with 9-1-1 activation and ends at the time of ED arrival. |

| ED | Patients who arrive at an ED (referrals, walk-ins, EMS arrivals). | Begins with patient arrival and ends with an admission order. Patients on EMS stretchers are an ED accountability. |

| Inpatient | Medical: Patients referred for inpatient care. Surgical: Patients referred to determine the need for a surgical procedure. |

Begins at the time of referral and ends with discharge or referral to community. Admitted patients in the ED fall into the inpatient accountability zone. |

| Community | Patients who do not require hospitalization but cannot function independently in the community.* | Begins with patient referral from the hospital or community. ALC (Alternate Level of Care) patients on inpatient units fall within the community accountability zone. |

Table 3. Program Accountability Zones (High-Level)

*Community programs include community care, continuing care, rehabilitation, mental health, palliative care, homecare help, assisted living or long-term residential care.

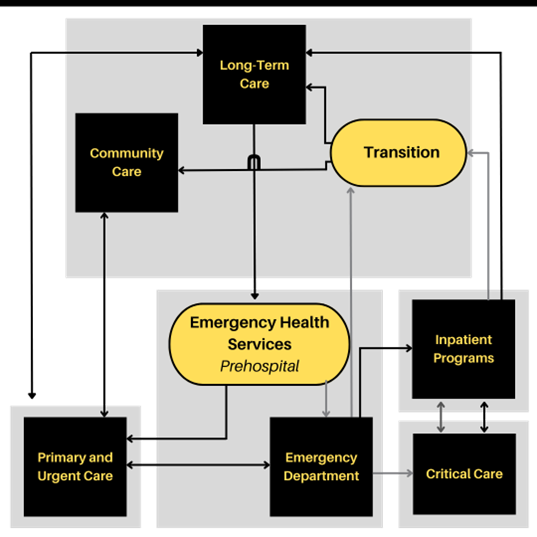

Accountability also shifts as patients flow through the system (Figure 19). It is obvious in the case of a patient requiring fracture fixation, a woman in labour, or a patient requiring mechanical ventilation, but it may be unclear at the margins. Program boundaries differ by hospital and may be dynamic, but accountability is always identifiable and can be clarified by facility-specific policies. If accountability is in dispute (e.g., the septic patient who is too sick for a medical unit but not sick enough for an intensive care unit), services at the relevant interface must resolve the disposition because these services best understand the clinical and operational factors in play.[11] (A detailed description of recommended referral and transition processes is available in Appendix 5, the Facility-Level Accountability Framework.)

Figure 19. Programs and Accountability Zones: Black boxes denote programs. Yellow ovals are inflow transitions to programs. Grey shaded areas are accountability zones: the ED is accountable for all arriving patients; inpatient programs are accountable for referred patients; community programs are accountable for patients designated appropriate for community- or alternate-level care.

Program Accountabilities include timely patient assessment and disposition; budget, space, and nursing care for program patients; and contingency plans for managing surges and queues. [11,12] Accountability is defined conceptually, as above, and quantitatively based on performance and time targets (See Table 4).

Ministries of Health must drive accountability planning and provide systems for measurement and reporting. They are accountable to assure population-capacity alignment, so that programs have the clinical infrastructure and resources required for patient care, assuming a high level of efficiency and appropriateness. They also establish the legislative and labour environment that make it possible for CEOs, boards, and regional leaders to be effective. Regional, facility and program leaders should implement care accountability frameworks that define conceptual accountability zones and access-related performance targets (Table 4).

Program Accountability = Timely patient assessment and disposition; budget, space, and nursing care for program patients, and contingency plans for managing surges and queues.

Performance Measurement

Progress toward accountability time targets should be reported as mean (average) values because these provide a measure of utilization. For example, the number of ALC patients multiplied by their mean ALC time = total hospital ALC utilization days. Percentile targets do not do this, and the latter may lead to unintended consequences where patients who are beyond a percentile wait time target (e.g., 90%) are left to wait even longer, because they have already “missed the target.” Time targets suggested here are optimal and not currently realistic in many settings. Programs and facilities should adopt a graded approach to meet these rather than lowering the bar. For example, begin with an ambulance offload target of 60 minutes for 6 months, then reduce to 45 minutes for 6 months, then to 30 minutes.

| Program | Process | Target |

| ED | Ambulance offload time in the ED | 30 minutes |

| ED | Time to ED triage | 10 minutes |

| ED | Time to ED physician, stratified by CTAS levels 1-5 | 0-120 minutes |

| ED | ED length of stay (LOS) for discharged patients | 4 hours |

| Inpatient | Consultation interval (referral to disposition decision) | 2 hours |

| Inpatient | Inpatient transfer time (admission order to unit transfer) | 2 hours |

| Inpatient | Mean hospital discharge time (with scheduled departures) | 11:00 am |

| Inpatient | Actual LOS/Expected LOS | 96% |

| LTC | Hospital beds occupied by ALC patients | <4% |

| LTC | Time from long-term care referral to transfer (ALC time) | 7 days |

| Hospital | Average hospital bed occupancy rate | 85-90% |

Table 4. Critical Access and Flow Targets by Accountable Program

Achieving Accountability

Most leaders and providers agree with the concept of accountability. It is logical that someone is accountable to ensure patients can access care. Despite conceptual agreement, accountability is difficult when capacity is limited (an argument for efficiency and thoughtful allocation); when demand surges (an argument for demand management); or when program beds and staff are blocked by patients awaiting care from a downstream program (an argument for queue management expectations). In spite of challenges, accountability must extend into the real world where surges occur, and systems are stressed. Accountability requires collaboration and innovation; when access failures occur and patients accumulate in the wrong places, leaders must be able to consult an accountability framework and identify which most responsible program will step up with a solution. All programs will face overwhelming resource and capacity challenges. Those that can lend capacity or temporarily support an adjacent stressed program should do so, knowing the favour will be returned.

Accountability Strategies

Accountability frameworks clarify patient care expectations, but strategies, especially surge contingencies and queue management plans, are necessary to move the responsibility beyond the conceptual stage. Programs should introduce many or most of the proactive access strategies described below.

Planning for ALL the Patients (Accountability for the Queue)

Most programs have queues. They highlight demand-capacity mismatches, situations where there are more patients requiring care than resources to provide care. There are many ways to address demand-capacity mismatches, with solutions differing by setting and program. [9,26,30,32-35,39] To better meet care needs, programs should develop service delivery plans that rationally allocate their people and resources to their target population, including patients who are waiting. [31,38,43] Without queue management expectations, access failures in one program create widespread dysfunction. To avoid compromising care elsewhere in the system, contingency plans must involve more than blocking access and deferring care elsewhere. In an accountable system, the program responsible for the wait would provide the waiting room. To address care gaps, some programs need more money, beds, or providers; others may need to re-examine care allocation, eliminate low-value activities, improve flow processes, increase efficiency, or develop surge strategies and queue management plans.

Program leaders generally have system perspective and recognize the need to care for target populations like people experiencing mental health challenges, emergency, or surgical patients. Front-line providers typically see accountability extending only to those they are actively caring for. Busy GPs in community practice rarely feel accountable for orphaned patients who cannot access primary care. Emergency providers are likely to think patients blocked on ambulance stretchers are an EMS problem, and inpatient providers may believe that admitted medical patients blocked in ED stretchers are a problem the ED should solve. [7] In fact, EMS leaders cannot solve ED care delays, EDs cannot solve inpatient delays, and inpatient programs cannot solve ALC (Alternate Level of Care) delays. Programs and providers must consider patients in their queue as a program concern; their staff can then view access and flow initiatives as positive solutions to internal problems, rather than unwanted changes imposed on them to solve someone else’s problem. [7,31,37,38,40]

If accountability extends only to patients already in care, several failure mechanisms arise. The program will not develop effective queue management policies, and providers will often resist or sabotage access initiatives because they believe waiting patients are not their responsibility. [7] Without queue management expectations, closing the front door and blocking access becomes the obvious default approach to demand-capacity mismatches. And even if the program could do better, people rarely strive to achieve expectations that they are unaware of.

Prioritizing Care Allocation: Matching Care Delivered to Care Required

If a patient is deteriorating in the hallway, while a stable patient is waiting for test results in a monitored ED stretcher, this is a bad care allocation decision.

Caring for some patients while leaving others in a queue is called rationing. Most programs are therefore in continuous rationing mode. Ethicists believe that if limiting resources is necessary, priority goes to patients with the greatest need and treatments with the greatest benefit. [31,39,41,42] In this context, need refers to a suboptimal health state, and benefit to an outcome improvement. Thoughtful care allocation decisions might therefore prioritize in the following order: [43]

- Lifesaving resuscitation

- Rapid recognition of critical illness

- Pain control

- Definitive acute care

- Ongoing convalescent care, and

- Comfort.

| PARADOXICAL CARE ALLOCATION

A retiree calls 9-1-1 when he is unable to awaken his 77-year-old wife at 08:30. They golfed the previous day, and he last saw her reading in bed at 04:00 when he was up to the bathroom. Paramedics find her semi-conscious (GCS 11) with decreased pain response on the left side. |

Standard hospital operating procedures illustrate that we do not always use rational frameworks to allocate care. [40] Undiagnosed and unstabilized patients with serious illnesses who are among the sickest in the hospital when they arrive, are often left in hallways without being assessed or stabilized because all beds are occupied (mostly by patients who are less ill). Once diagnosed, treated, and stabilized, they graduate to a room, a nurse, a bed, and a toilet. The best care locations are occupied by stable, treated patients no longer at risk of death or disability, and those convalescing or awaiting discharge—even those who no longer need to be in hospital. [43] Leaving suffering or acutely ill patients in the waiting room while assuring comfort and privacy for convalescing patients (who are accruing minimal health benefit) is a misallocation of care.

If a patient is deteriorating in the hallway, while a stable patient is waiting for test results in a monitored ED stretcher, this is a bad care allocation decision. If a dischargeable inpatient remains in a hospital bed waiting for a test or a ride home, while another patient with an acute stroke languishes in a waiting room, this is bad care allocation.

Triage and Reverse Triage

Triage means rapidly identifying high-needs patients and directing care resources to them. [44] Reverse triage means redirecting resources away from patients whose need and benefit have diminished. Reverse triage can free up substantial care resources, improve the balance of care delivery, and reduce delays for many sick patients. [45-48]

Optimizing Inflow

Patients with the greatest need arrive at a program’s front door. Whether the diagnosis is myocardial infarction (heart attack), hemothorax (the accumulation of blood in the space between the lungs and the chest wall) or dehydration, the patient’s need and benefit are front-loaded. [43] Optimizing inflow is an important strategy to match care delivery. At the front door, where time is measured in minutes or hours, high-need patients receive high benefit care. Emergency arrivals are resuscitated, diagnosed, and stabilized. Medical and surgical patients receive advanced expertise and aggressive or interventional care. Later, during the inpatient stay, patient transformation to wellness continues, but illness severity (need) and treatment intensity (benefit) diminish. [11] At the back end, where time is measured in days or weeks, stable convalescing patients consume many more bed and nursing hours, while accruing less health benefit. For older patients with frailty who achieve ALC status, additional hospital days have a greater likelihood of causing more harm than good because wasting and cognitive decline manifest. [25,27,49] Despite this, ALC patients are given higher priority for scarce inpatient beds than incoming acutely ill patients who would actually benefit from hospital care.

To assure care for priority patients, all programs require triage, reverse triage, and expedited inflow processes.

Adding Resources at Bottlenecks

Managing bottlenecks is the most effective way to reduce queues. [9,50,51] By definition, the bottleneck (location of the queue) is at the program’s inflow point, where clinicians, the critical resource, make diagnoses and determine dispositions. Decision-makers at the front door reduce delays for the sickest patients, expedite early high-benefit treatments, and avert disasters by detecting unrecognized serious illness. [43,52-55] They make patient-level risk assessments and rapid-care allocation decisions, triaging needy patients to expedited care (e.g., a resuscitation room) when required. They also preserve scarce resources by removing lower priority patients from the queue or diverting them to more appropriate care elsewhere.

Surge strategies may include transfers, service agreements, capacity enhancement, discharge lounges, accelerated discharges, overcapacity care spaces, and protocols for the expedited transfer of ALC patients to transition units or community overcapacity care locations.

It’s a Small Problem

A recent study of 1.8 million ED visits in 12 Canadian cities estimated the high acuity access gap at 25 hospitals by multiplying the number of arriving CTAS (Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale) 1-3 patients by their average delay to reach an ED care space. [56] For each hospital, this access gap represents the number of stretcher or bed hours required to provide timely care for all arriving high acuity patients. The study also reported each hospital’s inpatient bed base (care capacity), excluding specialty areas like maternity. The median (middle value) inpatient bed base (total number of beds available) for the study hospitals was 462, which equates to over 4 million bed hours per hospital per year. The average emergency access gap which reflects the amount of time high-acuity patients were collectively blocked outside EDs, was 46,000 hours per site per year.

This is a sizeable gap during which many patients will suffer adverse events; but it represented only 1.14% of inpatient capacity at the corresponding hospitals, a gap that could be eliminated by a 90-minute reduction in average inpatient length of stay (LOS) for a hospital with 30,000 separations per year. This suggests that if access block is viewed as a whole hospital problem—rather than concentrated in the ED—it could be substantially mitigated by modest efficiency improvements, with or without new capacity. [56]

|

OPTIMIZING FLOW At 2pm, an ED director is called to address a crisis. Thirty of the ED’s 42 stretchers are blocked by admitted patients waiting for an inpatient bed. There are 15 patients in the ED waiting room, 6 ambulance crews blocked in the hallway, and no available ED care spaces. In the waiting room, people are moaning, someone is vomiting into a wastebasket, and a patient is lying on the floor, unable to get up. It looks like a war zone, she thinks, but it’s often like this. Twelve hours later, while working the night shift, she notices that the waiting room is empty and there are no EMS crews waiting. The number of hospital beds has not increased, but most of the admitted patients have been transferred to inpatient units, and all patients are in care spaces, just like every other night at 2am. She has an epiphany. Emergency access block is as much about flow as it is about capacity. Patients flow rapidly into the ED, but it takes 12 hours for an admitted patient to flow from the ED to a hospital bed. Rapid ED inflow plus slow ED outflow equals ED care delays and bad outcomes. Even if there are enough hospital beds, slow inflow processes mean the hospital doesn’t catch up with waiting patients until after midnight. |

Pull Systems

Programs typically do not take over care immediately when patients are admitted or when the need for care is apparent. Rather, care units control inflow by “pulling” when unit capacity is available, and they are “ready.” Readiness is based on perceived ability to provide care under usual operating conditions. Unfortunately, during patient surges when demand exceeds apparent capacity, usual procedures may be insufficient to address patient need. Many programs have contingencies to free up capacity during surges, but in a “pull” system where patient inflow can be stopped at any time (by not pulling), it might not seem necessary to activate stressful contingencies or deviate from normal processes. Pull systems are provider-driven and tend to protect operational norms, even during periods of high patient demand.

Push Systems and Overcapacity Protocols

In a push system, patients requiring care would flow rapidly by default to the right (most accountable) program. At times when pull systems are failing and when access block compromises care, a push contingency may be necessary. Overcapacity protocols (OCP) are such a contingency. [57] Under conditions of severe access block, OCP temporarily removes the ability to block inflow, and pushes patients more rapidly than usual to the most accountable program, forcing it to activate its surge contingencies. [19,58,59] OCPs prioritize patient need over system norms, and are patient-focused. But the receiving programs are stressed because their control over inflow is temporarily removed.

Some are uneasy with the concept. Their understandable response is, “You can’t just push patients into a full hospital (or emergency department).” This is intuitive. But the alternative, blocking sick patients outside without care, is even less acceptable. Nor is it feasible to have an open ED with a closed hospital, particularly when ED capacity is a fraction of hospital capacity and when challenges an institution could manage would overwhelm a single unit.

If we agree that high acuity patients need timely care—and if there are too many medical, surgical, pediatric, mental health or geriatric patients in the hospital—it’s more appropriate to distribute small numbers to the most accountable medical, surgical, pediatric, mental health and geriatric units than it is to contain them all in one emergency department that’s already overcrowded and doesn’t have the resources or expertise to care for them. [59]

Expedited inflow for acutely ill patients will sometimes push convalescing patients into less optimal situations or trigger earlier discharges (reverse triage). While not perfect, this is the most ethical approach when care resources are finite, and it may even benefit ALC patients who are pushed to less acute settings. [60,61,62] Overcapacity protocols have proven safe, with low rates of ICU transfer and mortality. [19,59,60,63] They reduce ambulance offload delays, as well as delays to emergency and inpatient care. They also liberate care spaces for sick patients and improve patient outcomes. [57,59,64,65,66] Supply-driven OCPs are common and generally fail, but demand-driven (patient-focused) protocols will usually succeed. A more detailed discussion of demand-driven overcapacity protocols can be found in Appendix 6.

Recommendations for Access Block and Accountability Failure

- Ministries of Health should initiate the introduction of accountability frameworks like those described here, which incorporate accountability zones, expectations, and performance targets.

- Ministries of Health should drive system accountability planning, assure population-capacity-alignment, and establish a legislative and labour environment (including financing) that allow hospital CEOs, boards, and regional authorities to be effective.

- Facility and program leaders should acknowledge the concept of accountability zones and develop real-time policies to clarify care accountability in unclear or disputed cases (see Accountability Zones).

- Facility and program leaders should implement accountability performance measures specifying timely patient access and flow targets for all programs (Table 4).

- Program leaders should develop effective queue management strategies and surge contingency plans that do not involve blocking access and deferring care to other programs.

- To improve patient access to care and achieve program accountability, program leaders should drive the implementation of many or most of the accountability strategies described in this document.

- Facilities should implement demand-driven overcapacity protocols that will be activated when pull systems are failing and access block is compromising care delivery. Overcapacity protocols should also bridge the hospital-to-community transition.

- Regional, facility and program leaders should implement accountability measurement and reporting systems. They should monitor care gaps and use defined performance measures to determine whether gaps are best addressed through new capacity, enhanced efficiency, or reallocation of existing resources. Where the root cause is capacity, they must advocate for new resources; where it is inefficiency or misallocation, they must demand change. [8]

References

- Barua B, Moir M. Comparing performance of universal health care countries. 2019. Fraser Institute. http://www.fraser institute.org. Accessed 20 Oct 2020

- Canadian Institute for Health Information. How Canada Compares: Results From the Commonwealth Fund 2020 International Health Policy Survey. https://www.cihi.ca/sites/default/files/document/how-canada-compares-cmwf-survey-2020-chartbook-en.pdf. Ottawa, ON: CIHI; 2021.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). OECD health statistics 2019. OECD. 2019

- Canadian Institute for Health Information. Sources of potentially avoidable emergency department visits. Ottawa, ON: CIHI 2014. https://secure.cihi.ca/free_products/ED_Report_ForWebEN_Final.pdf. Accessed May 10, 2022

- Berchet C. The Directorate for Employment, Labour and Social Affairs Health Committee of the OECD. Emergency care services: Trends, drivers and interventions to manage the demand. http://www.oecd.org/officialdocuments/publicdisplaydocumentpdf/?cote=DELSA/HEA/WD/H WP(2015)6&docLanguage=En. Accessed May 6, 2022

- Health Quality Council of Alberta. Review of the quality of care and safety of patients requiring access to emergency department care. 2012. Available at: https://hqca.ca/wp- content/uploads/2022/01/EDCAP_FINAL_REPORT.pdf. Accessed May 6, 2022

- Ramanujam R, Rousseau D. The challenges are organizational not just clinical. J Organiz Behav 2006;27:811-27

- Harber B, Ball E. Redefining accountability in health care. Managing Change 2003;(Spring):13- 22

- Rutherford PA, Anderson A, Kotagal UR, Luther K, Provost LP, Ryckman FC, Taylor J. Achieving Hospital-wide Patient Flow (Second Edition). IHI White Paper. Boston, Massachusetts: Institute for Healthcare Improvement; 2020. (Available at www.ihi.org).

- Kreindler SA. The three paradoxes of patient flow: an explanatory case study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):481. doi:10.1186/s12913-017-2416-8 Innes GD. Access block and accountability failure in the healthcare system. CJEM. 2015;17(2):171-179.

- Atkinson P, Innes GD. Patient care accountability frameworks: the key to success for our healthcare system. Can J Emerg Med 2021;23:274-76

- Javidan AP, Hansen K, Higginson I, et al. White paper from the emergency department crowding and access block task force [Internet]. International Federation for Emergency Medicine; 2020 June. https://www.ifem.cc/resource-library/. Accessed May 10, 2022

- Shen Y, Hsia RY. Association between ambulance diversion and survival among patients with acute myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2011;305(23):2440–47

- Chalfin DB, Trzeciak S, Likourezos A, et al. Impact of delayed transfer of critically ill patients from the emergency department to the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2007;28(6):1477-83.

- Geelhoed GC, de Klerk NH. Emergency department overcrowding, mortality and the 4-hour rule in Western Australia. Med J Aust. 2012;196:122-26.

- Jo S, Jeong T, Jin YH, et al. ED crowding is associated with inpatient mortality among critically ill patients admitted via the ED. Am J Emerg Med 2015;33:1725–31

- Guttmann A, Schull MJ, Vermeulen MJ, Stukel TA. Association between waiting times and short term mortality and hospital admission after departure from emergency department: population based cohort study from Ontario, Canada. BMJ. 2011;342: d2983

- Viccellio A, Santora C, Singer AJ, Thode HC, Henry MC. The association between transfer of emergency department boarders to inpatient hallways and mortality: a 4-year experience. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;54(4):487-91.

- Singer AJ, Thode HC, Viccellio P, Pines JM. The association between length of emergency department boarding and mortality. Acad Emerg Med. 2011;18(12):1324-1329.

- Boulain T, Malet A, Maitre O. Association between long boarding time in the emergency department and hospital mortality: a single-center propensity score-based analysis. Intern Emerg Med 15, 479–489 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11739-019-02231-z

- Sprivulis PC, DaSilva JA, Jacobs IG, et al. The association between hospital over-crowding and mortality among patients admitted via Western Australian emergency departments. Med J Aust 2006; 184:208–12

- Sun BC, Hsia RY, Weiss RE, et al. Effect of emergency department crowding on outcomes of admitted patients. Ann Emerg Med. 2013;61:605-11

- Richardson DB. Increase in patient mortality at 10 days associated with emergency department overcrowding. Med J Aust 2006;184:213–16

- McIsaac DI, Abdulla K, Yang H, et al. Association of delay of urgent or emergency surgery with mortality and use of health care resources: A propensity score–matched observational cohort study. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2017;189(27):E905-E912

- Canadian Institute for Health Information, Understanding Emergency Department Wait Times: Access to Inpatient Beds and Patient Flow (Ottawa: CIHI, 2007). https://secure.cihi.ca/free_products/Emergency_Department_Wait_Times_III_2007_e.pdf. Accessed April 7, 2023.

- Robert B, Sun AH, Sinden D, et al. A case-control study of the subacute care for frail elderly (SAFE) unit on hospital readmission, emergency department visits and continuity of post-discharge JAMDA 22 (2021) https://www.jamda.com/action/showPdf?pii=S1525-8610%2820%2930631-9. Accessed May 16, 2022

- Institute of Medicine. Hospital-based emergency care: at the breaking point. Washington (DC): National Academies Press; 2006

- Liew D, Liew D, Kennedy MP. Emergency department length of stay independently predicts excess inpatient length of stay. Med J Aust 2003;179(10):524-6.

- Richardson DB. The access-block effect: relationship between delay to reaching an inpatient bed and inpatient length of stay. Med J Aust 2002;177(9):492-5.

- Girod J, Beckman AW. Just allocation and team loyalty: a new virtue ethic for emergency medicine. J Med Ethics 2005; 31:567-70.

- Eckstein M, Chan LS. The effect of emergency department crowding on paramedic ambulance availability. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;43:100-105

- Hoot NR, Aronsky D. Systematic review of emergency department crowding: causes, effects, and solutions. Ann Emerg Med 2008;52(2):126-36

- Kobayashi KJ, Knuesel SJ, White BA, et al. Impact on length of stay of a hospital medicine emergency department boarder service. J Hosp Med. 2019 Nov 20;14:E1-E7

- Moskop JC, Sklar DP, Geiderman JM, et al. Emergency department crowding, part 2 – barriers to reform and strategies to overcome them. Ann Emerg Med 2009;53:612-7

- Rabin E, Kocher K, McClelland M, et al. Solutions to emergency department “boarding” and crowding are underused and may need to be legislated. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31(8):1757- 66

- Vearrier L, Henderson CM. Utilitarian Principlism as a Framework for Crisis Healthcare Ethics. HEC Forum. 2021;33(1-2):45-60. doi:10.1007/s10730-020-09431-7

- Smith R, Hiatt H, Berwick D. Shared ethical principles for everybody in health care: a working draft from the Tavistock group. BMJ 1999;318:248-51

- Doyal L. Needs, rights and equity: moral quality in healthcare rationing. Qual Healthc 1995;4:273-83

- GD Kelen, 37 Scheulen. Emergency department crowding as an ethical issue. Acad Emerg Med 2007; 14:751-754

- Hasman A, Hope T, Osterdal LP. Health care need: three interpretations. J Appl Philosophy 2006;23:145–56.

- Cookson R, Dolan P. Principles of justice in health care rationing. J Med Ethics 2000;26:323–9

- Innes GD, Pauls M, Campbell SG, Atkinson P. Our responsibility to assess patients is not limited to those in beds. Can J Emerg Med. 2019; 21(5):580-586

- Lin JY, Anderson-Shaw L. Rationing of resources: ethical issues in disasters and epidemic situations. Prehosp Disaster Med 2009;24:215–21

- Kuschner WG, Pollard JB, Ezeje-Okoye S. Ethical triage and scarce resource allocation during public health emergencies. Hosp Topics 2007;85:16–24.

- Kelen G, McCarthy ML, Kraus CK, et al. Creation of surge capacity by early discharge of hospitalized patients at low risk for untoward events. Disaster Med Public Health Prep 2009;3 (Suppl 1):S1–7.

- Kelen G, Kraus CK, McCarthy ML, et al. Inpatient disposition classification for the creation of hospital surge capacity. Lancet 2006;368:1984–90

- Satterthwaite PS, Atkinson CJ. Using ‘reverse triage’ to create hospital surge capacity: Royal Darwin Hospital’s response to the Ashmore Reef disaster. Emerg Med J. 2012 Feb;29(2):160-2

- Sutherland JM, Crump RT. Alternative level of care: Canada’s hospital beds, the evidence and options. Healthc Policy. 2013 Aug;9(1):26-34

- Goldratt E. The goal: a process of ongoing improvement. 3rd ed. Great Barrington,MA: North River Press; 2014

- Senge P. The Fifth Discipline. New York: Doubleday/Currency; 1990:170-171

- Rowe BH, Guo X, Villa‐Roel C, et al. The role of triage liaison physicians on mitigating overcrowding in emergency departments: a systematic review. Acad Emerg Med 2011;18:111– 20.

- Abdulwahid MA, Booth A, Kuczawski M, Mason SM. The impact of senior doctor assessment at triage on emergency department performance measures: systematic review and metaanalysis of comparative studies. Emerg Med J 2016;33:504–13.

- Wiler JL, Gentle C, Halfpenny JM, Heins A, Mehrotra A, Mikhail MG, Fite D. Optimizing emergency department front-end operations. Ann Emerg Med. 2010 Feb;55(2):142-160

- Burström L, Engström ML, Castrén M, et al. Improved quality and efficiency after the introduction of physician-led team triage in an emergency department. Ups J Med Sci. 2016;121(1):38-44

- Innes GD, Sivilotti M, Ovens H, McLelland K, et al. Emergency Department Access Block: ASmaller Problem Than We Thought. Can J Emerg Med 2019. Mar;21(2):177-85

- Innes G, McRae A, Holroyd B, et al. Policy-driven improvements in crowding: system-level changes introduced by a provincial health authority and its impact on emergency department operations in 15 centers. Acad Emerg Med. 2012;19:S4-S5

- Villa-Roel C, Guo X, Holroyd BR, et al. The role of full capacity protocols on mitigating overcrowding in EDs. Am J Emerg Med 2012;30(3):412-20

- Lee MO, Arthofer R, Callagy P, Kohn MA, Niknam K, Camargo CA Jr, Shen S. Patient safety and quality outcomes for ED patients admitted to alternative care area inpatient beds. Am J Emerg Med. 2020 Feb;38(2):272-277

- Bai AD, Dai C, Srivastava S, et al. Risk factors, costs and complications of delayed hospital discharge from internal medicine wards at a Canadian academic medical centre: retrospective cohort study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):935

- McRae A, Lang E, Li B, Wang D, et al. Safety of a system-wide intervention to address access block in 13 congested hospitals. Can J Emerg Med 2013;15(S1):6-7

- Kaboli PJ, Go JT, Hockenberry J, et al. Associations between reduced hospital length of stay and 30-day readmission rate and mortality: 14-year experience in 129 Veterans Affairs hospitals. Ann Intern Med. 2012 Dec 18;157(12):837-45

- Ben Shoham A, Munter G. The association between hallway boarding in internal wards, readmission and mortality rates: a comparative retrospective analysis, following a policy change. Isr J Health Policy Res. 2021;10:8. Published 2021 Jan 27. doi:10.1186/s13584-021- 00443-3

- Kenen J. Full Capacity Protocol: Simple changes can transform a hospital. Altarum Institute Health Policy Forum. Feb. 14, 2011. http://www.healthpolicyforum.org/2011/02/newsanalysis-full-capacity-protocol-simple-changes-can-transform-a-hospital/index.html. Accessed May 16, 2022

- McRae AD, Wang D, Innes GD, et al. Benefits on EMS offload delay of A provincial ED overcapacity protocol. presented at the International Congress of Emergency Medicine, June 2012, Dublin, Ireland

- Viccellio P, Zito JA, Sayage V, et al. Patients overwhelmingly prefer inpatient boarding to emergency department boarding. J Emerg Med. 2013 Dec;45(6):942-6.