Editors: Alecs Chochinov, Grant Innes, Daniel Kollek, Sara Kreindler, David Petrie

A Systems Approach to the Future of Emergency Care

“Healthcare is at a watershed moment. The COVID pandemic and growing care shortfalls since, have underscored the urgent need to embark on fundamental healthcare redesign. We cannot wait passively for the future to evolve while our patients suffer harm. We hope this project will empower emergency providers and catalyze others, within and beyond healthcare, to help us plan a better future.”

Chapter 1 : Introduction to EM:POWER

Despite being a wealthy nation with a highly trained workforce, Canadian hospitals provide substandard access to emergency care. Too often our patients face treatment delays that cause frustration and adverse outcomes. Triage lineups, packed waiting rooms, ambulances unable to offload, waiting room disasters, physician shortages, rising stress levels, ED closures, and dispirited nurses leaving for more sustainable careers—it’s a vicious cycle of demand, dysfunction and distress that threatens emergency care on a national basis. [1–4] Some blame COVID for our current predicament, but although it may have been the last straw, it wasn’t the root cause. Instead, COVID exposed our system’s lack of resiliency and inability to respond to demand surges, anything from expected daily inflow fluctuations to unexpected ice storms and pandemics. After decades of progressive dysfunction, why are emergency departments (EDs) still getting worse? Some of the major causes are summarized below:

The Decline and Fall of the Primary Care Health Home

Many Canadians cannot get a family physician, and few can access same-day, next-day, or after-hours appointments. As a result, EDs increasingly provide primary care services. [6,7] A regionally rostered, multi-disciplinary, same or next-day accessible primary care (medical) home is the foundation of a functional healthcare system, required by all Canadians. Accessible primary care could address many low acuity, time-sensitive complaints. More importantly, it would address prevention, early identification, and provide follow-up for complex continuing care over time—for which emergency departments are not designed.

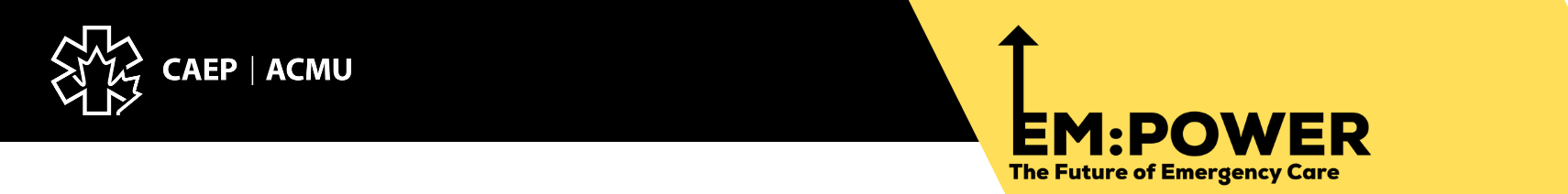

Figure 3. Percentage of survey respondents who said they had access to same-day or next-day appointment with their family doctor. All 38 countries in the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development), including Canada, have private delivery of publicly-funded health services. (Canadian Institute for Health Information. How Canada Compares: Results From the Commonwealth Fund’s 2020 International Health Policy Survey of the General Population in 11 Countries. Ottawa, ON: CIHI; 2021.)

System-Wide Access Failure

Illnesses and injuries happen 24/7, but Canada compares poorly to other OECD countries when it comes to providing access to primary care, specialists, elective surgery, and advanced imaging. [6,7] Healthcare services operate primarily on scheduled appointments between 8:30 and 5:00, Monday to Friday, with prolonged waits for almost everything. [6,7] Accessibility is a core principle of the Canada Health Act, yet there’s usually only one door open for Canadians who have unexpected health problems. [5]

Growing dependence on hospital-based technology and unacceptable waits for consultation and outpatient testing drive many patients to emergency departments with expectations of an immediate CT scan or specialist assessment. Such reliance places pressure on ED staff and resources, which drives up wait times, lengths of stay, as well as compromising ED efficiency and effectiveness. [1,2]

|

GROUNDHOG DAY FOR PATIENTS An 88-year-old man with bladder inflammation from radiation therapy develops bloody urine and goes to the ED. There, they irrigate his bladder through a catheter, but the bleeding continues, so they consult a urologist. The urologist will not come to the ED, but provides advice over the phone: daily home care bladder irrigation and return to the ED if he has problems. At home, the nurses cannot control the bleeding, and tell him to return to the ED. At his second ED visit, staff again irrigate his bladder repeatedly and give him a transfusion because he has lost so much blood. They again consult the urologist, who after reiterating the earlier phone advice, states that the urology ward is full, so the nurse arranges a clinic appointment in 6 weeks to decide whether he needs a more definitive bladder cauterization procedure. At home, blood clots clog his catheter, causing overflow bleeding into his clothing, sheets, and carpet. Painful episodes of bladder distention prevent him from sleeping, and blood loss makes him weaker. He learns to flush his own catheter at night when home care is not available. His Primary Care Physician is away, with a phone message advising patients to go to emergency for any urgent medical concerns. The patient himself knows the limits of that approach. His son visits from out of province, watches a YouTube video describing bladder irrigation, buys his own supplies and flushes his father’s bladder 3 times daily, but the bleeding continues. They reluctantly return to the ED, where emergency staff again flush his bladder and consult a different urologist. The patient has now had three ED visits totalling 36 hours, and likens his experience to the movie ‘Groundhog Day.’ Prior to the bleeding, he was golfing and gardening. Now he is sleep-deprived, anemic, weak, and expressing a wish to die. His son does not think his dad is safe to go home, but doesn’t know what his options are. |

Emergency departments become the default destination when patients are unable to receive care from the right providers in the right place, whether or not emergency providers have the necessary expertise or resources.

When patients who face long delays for specialist appointments or imaging studies become frustrated, or their condition deteriorates, they land in emergency departments. Surgical patients are told to go to an ED if they develop post-op problems. [7] Community providers direct patients to the ED for a second opinion, diagnostic testing, or simply out-of-hours care. When long-term care facilities cannot manage elderly residents, they transport them to emergency departments, not because EDs have geriatric expertise, but because no one else is available to see the patient. Family physicians who need urgent surgical or specialist advice instead send their patients to an ED because there are no urgent specialty referral pathways. Marginalized patients who cannot access care elsewhere depend heavily on EDs, and half of their visits are for non-urgent concerns. [7]

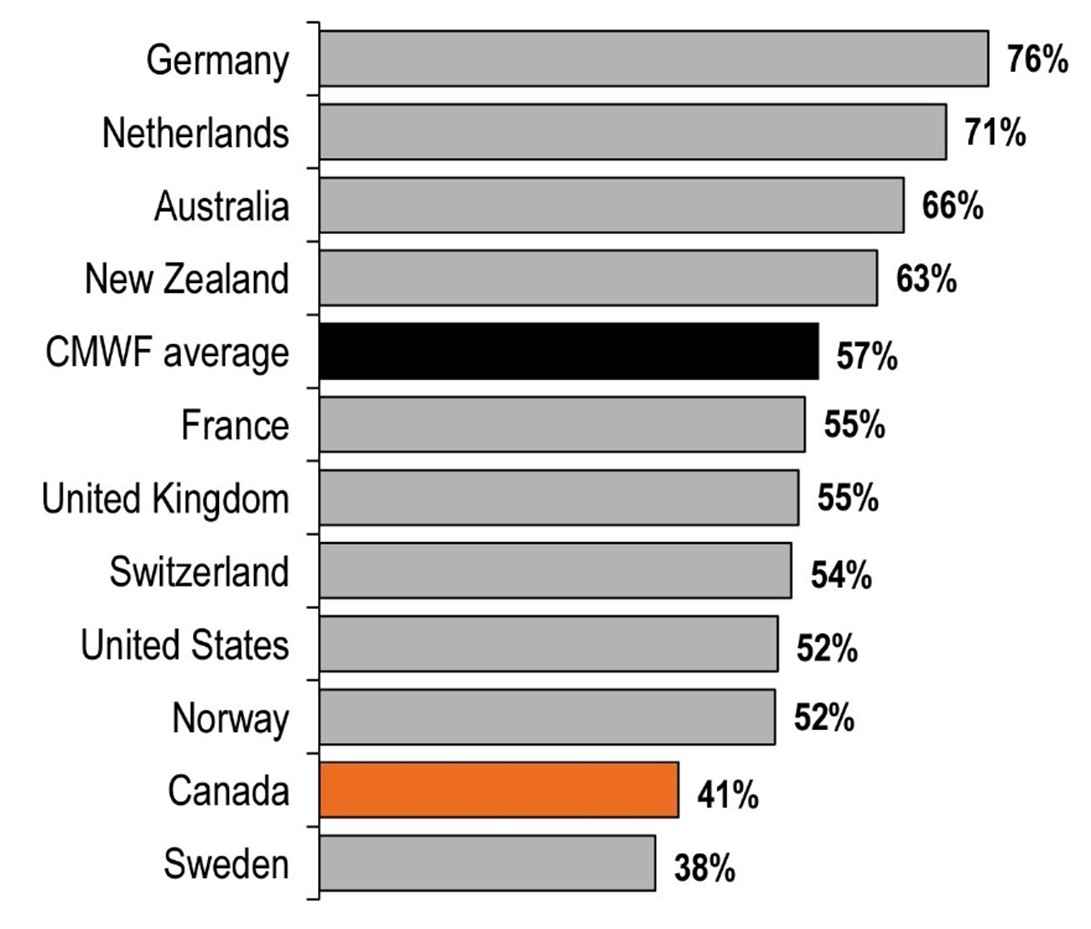

Figure 4. Percentage of survey respondents who said they waited less than 4 weeks for a specialist appointment. (Canadian Institute for Health Information. How Canada Compares: Results From the Commonwealth Fund’s 2020 International Health Policy Survey of the General Population in 11 Countries. Ottawa, ON: CIHI; 2021.)

Patient Complexity

Our aging population has a high prevalence of chronic disease and multiple comorbidities that require complex specialty care. While in the past, ED patients had acute problems like heart attacks or trauma, today they are often elderly with chronic multi-organ disease, and subacute or long-term deterioration. They are frequently unable to access appropriate care in the community and fail to cope in their home setting because of weakness, alterations in their mental state or lack of basic supports. They often require prolonged investigation and care processes that consume many hours or days, and their management is likely to require skill, knowledge and resources that are not part of the ED tools or resources. This might range from stabilizing complex chronic disease, to negotiating accelerated procedural access or navigating placement and follow-up care for older adults in crisis.

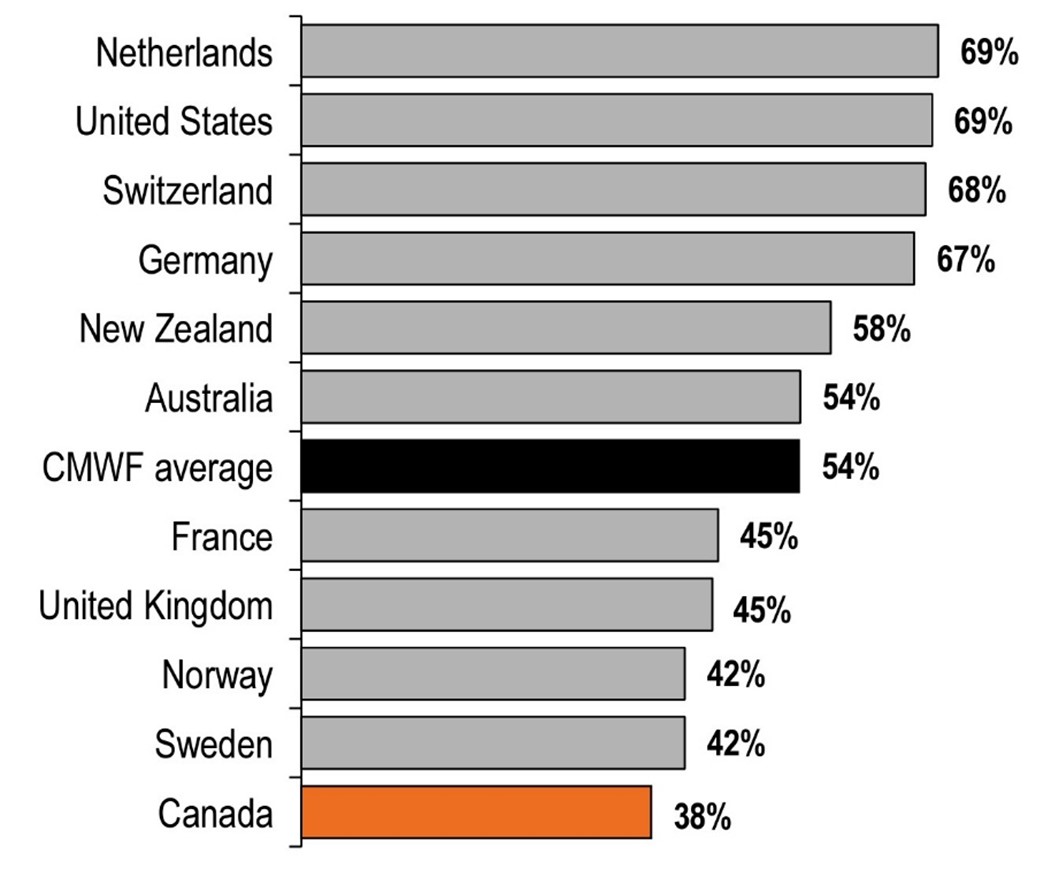

Figure 5. Percentage of survey respondents who said they waited less than 4 months for elective surgery. (Canadian Institute for Health Information. How Canada Compares: Results From the Commonwealth Fund’s 2020 International Health Policy Survey of the General Population in 11 Countries. Ottawa, ON: CIHI; 2021.)

System Complexity

Many leaders have failed to grasp that in today’s medical environment, traditional, top-down command and control initiatives are likely to fail or produce undesired effects. Healthcare has become a complex adaptive system that behaves more like an ecosystem, with multiple loci of influence, and no single chain of command. Interactions between constituent parts (especially human parts) are unpredictable and constantly changing. Effective leaders learn to work with uncertainty and enable innovation from all parts of the system, while making sure that when trying to improve one aspect, the overall system is not accidentally made worse.

Long-Term Care Shortfalls

Long-term care and community care are stretched to capacity. They’re often unable to accept patients with complex needs. As a result, ~15% of hospital beds are blocked by Alternate Level of Care (ALC) patients who no longer require hospitalization but aren’t able to manage in the community and have no viable discharge destination. The resulting loss of hospital capacity compromises the inflow of sick patients from emergency departments and is a major cause of acute care and emergency access block. Access block pervades the system at all levels. Patients in rural and underserviced areas face additional barriers to access (see Appendix 1, which can be found at the end of this report). Many who require specialized investigation and treatment are temporarily kept in small facilities with none of the necessary resources. This is because overstressed regional and tertiary centers have declined care, or transport capability is inadequate.

Hospital Access Block

Hospital Access Block is the greatest threat to emergency care. When inpatient programs cannot manage their patients, large numbers of those who are admitted and who should be in hospital beds are left on ED stretchers. These “boarding” inpatients endure long waits, sometimes for days, on hard narrow gurneys in crowded EDs without privacy, sleep, or bathroom access. They occupy many or most ED nurses and care spaces, decimating the ability to provide emergency care. In domino fashion, this forces acutely ill and injured patients to languish in waiting rooms, prevents ambulances from offloading, and compromises emergency responses for patients in the community calling 911.

To prevent delay-related disasters, many ED physicians now try to assess patients in waiting rooms and ambulance hallways. But with an overwhelming number of undifferentiated, unmanaged, chronically unwell, and frustrated patients at the front door, ED attention is increasingly diverted from the diminishing proportion of those who are high-risk and become hidden in the crowd. As a result, patients with life-threatening conditions are left in waiting rooms with unrecognized heart attacks, surgical emergencies, or brain hemorrhages. Too often, this leads to disastrous outcomes and media headlines that highlight apparent ED failures, when in reality, they are system failures.

Two decades of research have demonstrated that emergency access block compromises care quality, causes patient suffering and dissatisfaction, infectious disease exposure, violence towards hospital staff, decreased physician and nursing productivity, prolonged care delays, medical errors, toxic work environments, provider burnout, negative effects on teaching and research and—most importantly—increased patient morbidity and mortality.

How Did We Get Here?

In the 1970s, it became apparent that while many aspects of healthcare were growing and evolving, care for the acutely ill and injured was falling behind. The specialty of emergency medicine arose because North American and international experts identified the need for better emergency training and advanced skills. Beginning in the 1970s, EM pioneers defined a unique body of knowledge, developed training programs, established clinical standards, and a professional identity. In 1980, these efforts led to the recognition of EM as a Royal College specialty, and a College of Family Physicians area of special competence, which gave rise to Canada’s dual EM certification pathways. In 2007, Pediatric EM became a Royal College subspecialty.

Advances in emergency knowledge and training, coupled with the concurrent evolution of poison centres, trauma systems, pre-hospital care, regionalized stroke centres, and advanced cardiac intervention pushed emergency care to the forefront. EM became a sought-after career and EM residency directors had their pick of applicants. By the 1990s, emergency care was in ascendency, but something happened on the way to the future.

Hospital Capacity Shortfalls

First, it was hospital closures. Policymakers believed care could be provided more effectively in the community, reducing the need for hospital beds (i.e., deinstitutionalization), and with health costs consuming the majority of provincial spending, the temptation to cut hospital funding was hard to resist. Governments cut the number of hospital beds by almost 40%, from 6.6 per 1,000 population to 4.1 in the 1990s. This partly reflected the move to day surgery, but also the closure of rural hospitals, psychiatric hospitals, extended-care facilities (exacerbating our current ALC problem), and general medical beds.

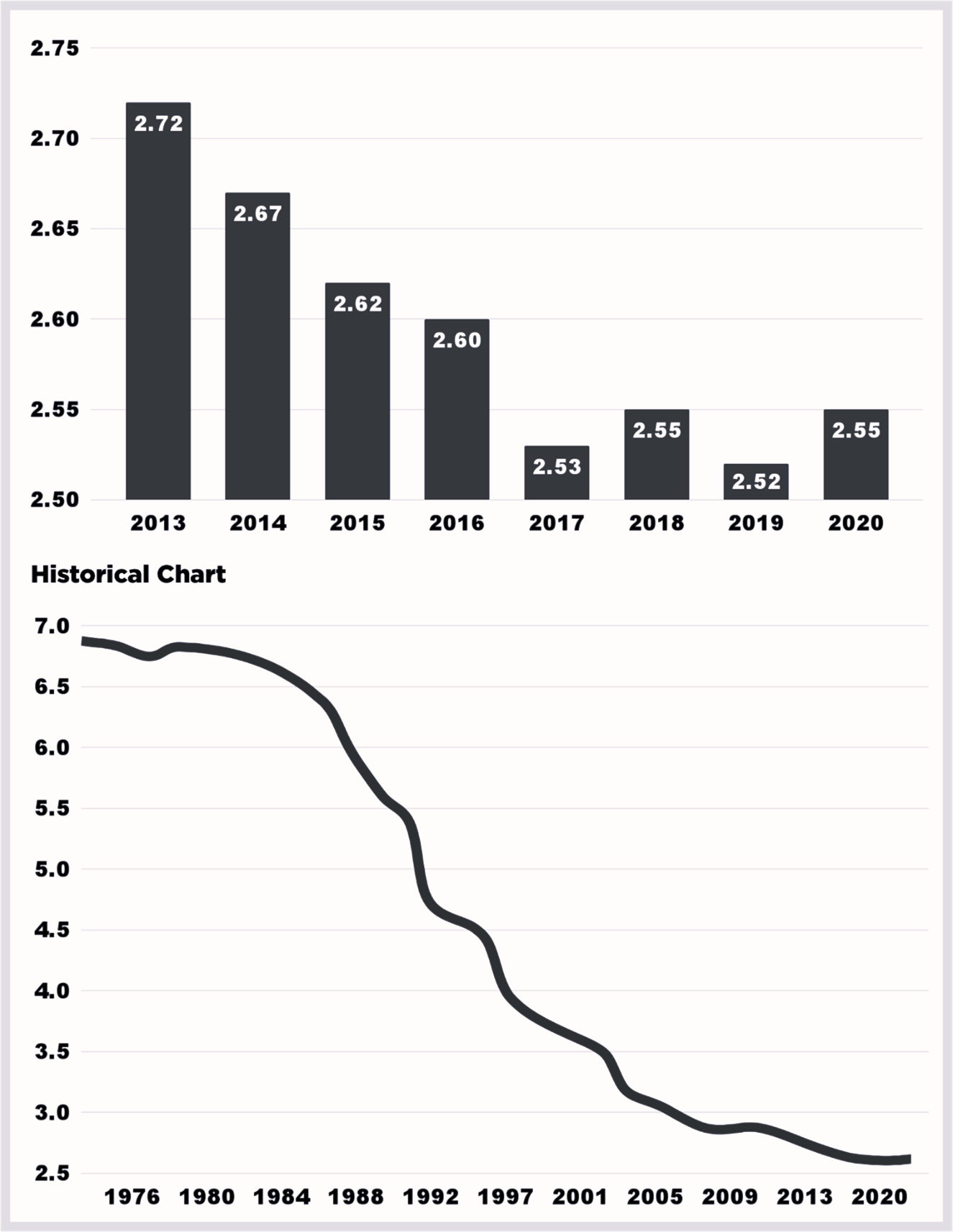

Figure 6. Number of Hospital Beds in Canada per 1000 population, 1976-2020

Unfortunately, cuts to facilities greatly exceeded new community resources, and the 1990s brought unmet needs in community and hospital care. ALC rates swelled, hospital occupancy rose, ED overcrowding appeared, and growing numbers of people with untreated mental health problems migrated to inner cities. Instead of responding to growing shortfalls with large-scale impactful system change which would require investment and long-term vision, governments too often followed election cycle timeframes to announce countless short-term fixes with transient, even illusory gains.

The funding cuts of the 1990s were reversed in the early 2000s; however, hospital beds per capita continued to fall, reaching 2.5 in 2020. [3] It remains unclear how many beds Canada would need if all care were provided in the most appropriate setting and organized efficiently. In the system as we know it, however, hospital occupancy rates have risen from under 80% in the 1980s to over 100% in many facilities today, leaving the system with no surge capacity and little or no resiliency.

Shortages of Health Human Resources

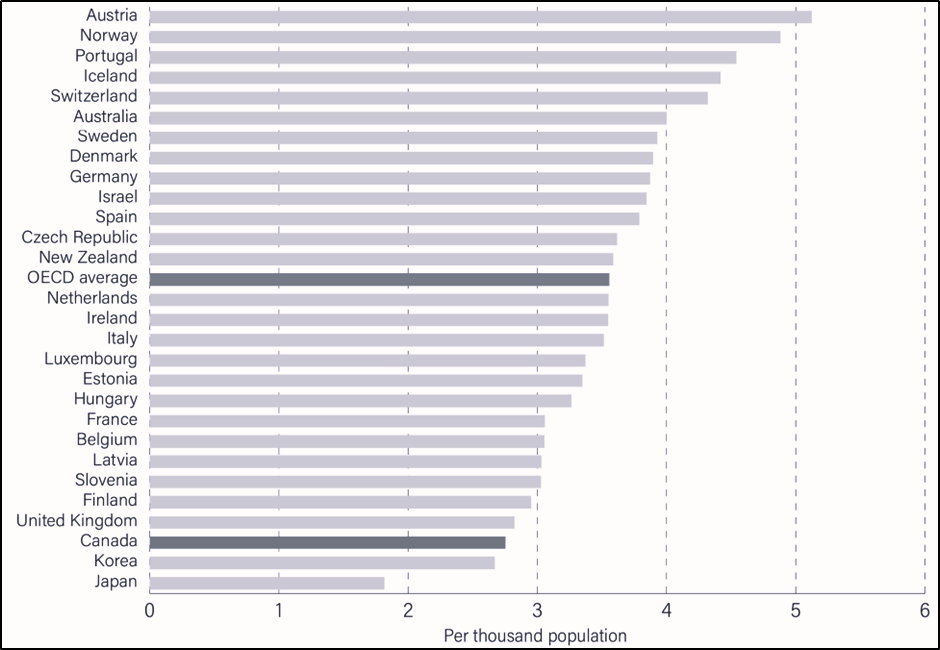

In the 1960s-1980s, physician supply rose steadily throughout the developed world, reflecting societal demand for medical services. This trend continued in many countries; however, Canada’s physician-to-population ratio dipped in the early 1990s due to policy decisions and unrelated factors. It did not rise again until a decade later, never catching up to the OECD average. Although today the number of Canadian physicians per capita has never been higher, changing practice patterns (partly reflecting the shifting demographics and priorities of the workforce) have brought a decline in the number of physician hours, while patient needs have increased. Physician supply is also geographically maldistributed, with acute shortages in rural areas.

Figure 7. Physicians per 1000 Population—Age Adjusted. OECD 2020

There is also a well-established nursing shortage across Canada and worldwide. While demand has grown, our supply of nurses has stagnated over the past decade. Ever-increasing work stress and overload, exacerbated by COVID-19, is now driving even more emergency (and other) nurses out of the field.

Inadequate Supports for a Complex, Aging Population

On top of the baby-boomer demographic bulge, medical advances have allowed many more people to survive to old age with complex comorbidities that require specialized care. However, that care—acute capacity, rehabilitation, long-term care, home care, specialists, and primary care—has not expanded proportionately. In addition, the nature and availability of publicly-funded services vary substantially by province and region. Most provinces lack a fully-resourced continuum of facility and community-based services, and therefore depend heavily on the most intensive form of long-term care, the nursing home. Canada’s per-population rate of long-term care beds is 54.3 per 1,000 (above the OECD average of 45.6). Even this supply falls far short of projected demand. Long-term care facilities are chronically overstretched and understaffed, a crisis that was tragically laid bare during the COVID-19 pandemic. Inadequate community support for our aging population increases demand on emergency departments and reduces the supply of inpatient beds for admitted patients.

Mental Health Challenges

The pandemic also drew attention to the inadequacy of current levels of publicly-funded mental healthcare. The hospital, community and long-term care sectors are struggling to cope with ever-escalating mental health demands. At the same time, exponential rises in substance-induced mental health disorders and addictions have placed a growing strain on ED resources, and contributed to escalating ED violence, with its attendant impacts on the ED workforce and provider burnout. [4]

Public Health Challenges

A population’s health is a product of nutrition, shelter, education, disease prevention and surveillance, hygiene, and safety from man-made or natural crises. Strong public health infrastructure minimizes the need for emergency treatment and shortens the duration of hospital care. Unfortunately, investments in public health and the social determinants of health are highly vulnerable to the political axe because the benefits of these investments are often delayed or invisible.

Over the last two decades, efforts to solve emergency crowding and access block have failed, generally because the root causes have not been addressed. Ironically—and contrary to conventional wisdom—our emergency care crisis was not caused by rising emergency visits, COVID, or too many low acuity patients attending emergency departments. The underlying problems are a lack of hospital beds for admitted patients, poor access to long-term, community and complex primary care, and rising levels of unmanaged mental health and addiction, all of which contribute to unmanageable demand on emergency departments.

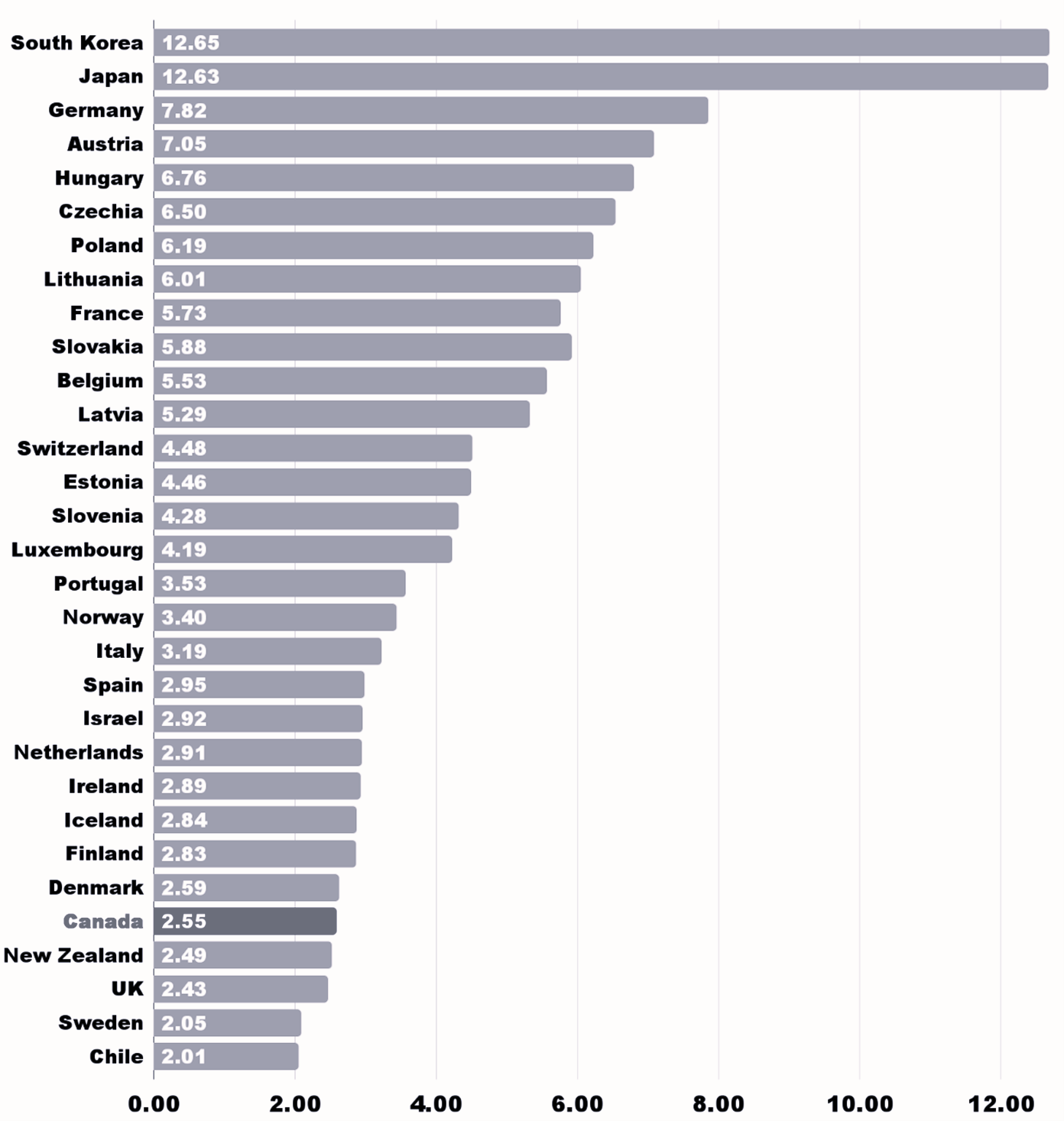

Figure 8. Hospital Beds per 1000 Population: Source OECD 2020

The growing challenges over recent years have been trying to fill gaps in primary and hospital care, addictions and mental healthcare, and the consequent inability to provide timely high-quality emergency care. As a result, many ED nurses and physicians have been driven away, creating a secondary and now critical provider shortfall.

What Must We Remedy?

This history reveals three key pathologies: population-capacity misalignment, lack of readiness and accountability failure.

Population-Capacity Misalignment

The Canadian healthcare system is plagued by a fundamental mismatch between the needs of the population and the services available. [5] Such misalignment reflects the fact that our delivery system was never deliberately designed in the first place. We face an ongoing shift in population needs from acute and episodic to chronic and complex, coupled with a tendency towards reactive and piecemeal policymaking. As the system’s universal contingency plan and last-resort provider for a myriad of needs (many of which it is ill-suited to manage) the ED bears the brunt of this misalignment. However, the problem pervades the health system: many patients are in the wrong place, and some lack a right place (i.e., their needs fall in the gaps between services).

For emergency departments to refocus on their core mission, it’s necessary to comprehensively assess population needs, determine what services are most suitable, and resource them appropriately. This process should follow the principles of population-based service design. [5] Without this rational approach, a random assortment of right and wrong patients will rapidly occupy any new capacity, leaving the system in the same quagmire as before. This already happened when supposedly short-stay and transitional overflow units for older adults were implemented without performance accountability. [6,7] No amount of planning can yield a perfect match between services and needs; there will always be gaps, exceptions, and local variations. However, we can aspire to a more nimble, integrated system, with fewer exceptions, narrower gaps, and less unwarranted variation than the non-system we now have.

Lack of Readiness

Our system is currently unable to address day-to-day demand fluctuations, let alone disasters, which are defined as unexpected demand that outstrips the usual ability to provide care. But disasters are inevitable; the only question is when and how often. To complicate matters, some disasters are local and sudden (e.g., the Humboldt Broncos bus crash) while others are widespread and escalate slowly (pandemics). Readiness, defined as the system’s ability to adapt to changes in the volume and nature of demand, generates resilience. This is required to address the inevitable surges that occur during normal times, and to meet the uncertain risks of the future. As COVID-19 showed us, a system without readiness is unstable and prone to failure, leading to avoidable morbidity and mortality, poor patient experience, negative population outcomes and increased system costs.

Accountability Failure

Accountability can and should be the evolutionary stressor required to drive beneficial system change. Its absence is a recipe for failure. Health programs and providers typically believe they’re accountable to patients already in their care, but not to patients in the queue, even if they have greater need. When demand outstrips apparent capacity, the obvious solution is to block inflow and create a wait line. This default is a primary coping mechanism for most programs, including emergency departments. It’s the opposite of a solution, but protects the program from evolutionary stressors, and effectively makes shortfalls in care delivery “someone else’s problem.” If closing doors is acceptable as a management response, then whoever is willing to see the patient (usually the ED) becomes accountable by default.

New system capacity is necessary, as discussed above, but it’s unlikely to solve existing access gaps without attached accountability. Developing a framework that clarifies accountability is a critical first step that must be established across the entire system. This includes primary and community-long-term-care, because failures in any program will have a domino effect that compromises other components of an interdependent system. Contingency plans for managing surges and queues must be incorporated into these accountability frameworks. The purpose isn’t to push frontline staff to work harder and harder, and to cope with a perpetual state of surge. Instead, the goals are to ensure:

- Patients can access care

- Programs are motivated to understand their accountability zone

- Care resources are aligned with population need

- Bottlenecks are managed

- Staffing models are optimized

- Flow processes are improved

- Surge contingencies are developed

- Queue management strategies are in place, and

- Effective demand-driven overcapacity protocols are activated when usual “pull” systems are failing.

These and other related processes are discussed in more detail in Section Three.

What Will Guide Us?

Canadians hold steadfastly to the notion of a just society, in which quality healthcare is a right of citizenship, available to all. Over 20 years ago, the Commission on the Future of Health Care in Canada published the Romanow Report, entitled Building on Values. [8] It supported the five principles of the Canada Health Act, most notably universality and accessibility, and recommended a sixth accountability.

In 2007, the Institute of Healthcare Improvement (IHI) introduced the Triple Aim, which established the triad of optimizing patient care, with improving population health, and lowering per capita costs as keys to healthcare transformation. [9] Over time, the concept evolved to a Quadruple Aim to include clinician well-being, based on research establishing clinician burnout as an impediment to achieving the original goals. More recently, the concept has expanded to become the Quintuple Aim, which incorporates health equity. Without addressing equity and social determinants of health (the biggest drivers of costs and population health outcomes) it is impossible to achieve the other aims, or a just society. (See Appendix 2.)

Figure 9. Value-based Care

Value-based Care synthesizes the five components of the Quadruple Aim into one concept: improving population health, patient experience, provider wellness and equity in a cost-effective way. [10] These values and principles have guided our deliberations on system redesign, and are the lens through which our recommendations are best viewed. There will inevitably be trade-offs and controversies: what if improving the experience of individual patients interferes with outcomes for the population? What if favouring cost expenditures in the present compromises the future? Large-scale change is never clear or easy, but without guiding principles we will continue to default to ad hoc decision-making, election-cycle planning, and the pressing needs of the day. [11] None of us wants that as our future state, nor should we accept it.

References

- Kreindler SA, Cui Y, Metge CJ, Raynard M. Patient characteristics associated with longer emergency department stay: a rapid review. Emerg Med J EMJ. 2016 Mar;33(3):194–9.

- Doupe MB, Chateau D, Chochinov A, Weber E, Enns JE, Derksen S, et al. Comparing the Effect of Throughput and Output Factors on Emergency Department Crowding: A Retrospective Observational Cohort Study. Ann Emerg Med. 2018 Oct 1;72(4):410–

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Health Care Resources: Hospital beds by sector [Internet]. 2023. Available from: https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?QueryId=49344

- Drummond A, Chochinov A, Johnson K, Kapur A, Lim R, Ovens H. CAEP position statement on violence in the emergency department. Can J Emerg Med. 2021 Nov 1;23(6):758–61.

- Kreindler S, Aboud Z, Hastings S, Winters S, Johnson K, Mallinson S, et al. How Do Health Systems Address Patient Flow When Services Are Misaligned With Population Needs? A Qualitative Study. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2021 Apr 26;11(8):1362–72.

- Mohammed Rashidul Anwar, Brian H Rowe, Colleen Metge, Noah D Star, Zaid Aboud, Sara Adi Kreindler. Realist analysis of streaming interventions in emergency departments. BMJ Lead. 2021 Sep 1;5(3):167.

- Kreindler SA, Struthers A, Star N, Bowen S, Hastings S, Winters S, et al. Can facility-based transitional care improve patient flow? Lessons from four Canadian regions. Healthc Manage Forum. 2021 May;34(3):181–5.

- Romanow RJ. Building on values. The future of health care in Canada. [Internet]. Commission on the Future of Health Care in Canada; 2002 Nov. Available from: https://publications.gc.ca/collections/Collection/CP32-85-2002E.pdf

- Institute for Healthcare Improvement. The IHI Triple Aim [Internet]. Institute for Healthcare Improvement; 2007. Available from: https://www.ihi.org/Engage/Initiatives/TripleAim/Pages/default.aspx

- Larsson Stefan, Clawson Jennifer, Howard Robert. Value-Based Health Care at an Inflection Point: A Global Agenda for the Next Decade. Catal Non-Issue Content [Internet]. [cited 2023 May 11];4(1). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1056/CAT.22.0332

- Sustainable Improvement Team and the Horizons Team. Leading large scale change: A practical guide [Internet]. Quarry Hill, Leeds: NHS England; 2018 Apr. Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp- content/uploads/2017/09/practical-guide-large-scale-change-april-2018-smll.pdf

- Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Canadian Institutes of Health Research – Institute of Health Services and Policy Research Strategic Plan 2021-2026. Accelerate Health Care System Transformation through Research to Achieve the Quadruple Aim and Health Equity for All. [Internet]. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: Canadian Institutes of Health Research; 2021. Available from: https://cihr- irsc.gc.ca/e/52481.html#section_1

- Chochinov A, Petrie DA, Kollek D, Innes G. EM:POWER: if not us, who? If not now, when? CJEM. 2023 Jan;25(1):11–3.

Chapter 2: What Have Emergency Departments Become and What Should They Be?

Appropriate care means the right care in the right place, but the ED is the wrong place for most patients. EDs are designed for 1–6-hour encounters; emergency teams are trained and equipped for acute problems and life-limb threats. We don’t provide quality inpatient care, intensive care, mental health intervention, chronic disease management, rehabilitation services, or primary/preventive healthcare, but these roles consume substantial ED resources.

Even when emergency care is complete, unfortunate patients who need hospitalization will face many more hours—sometimes days—in the ED before an inpatient bed becomes available. It’s unacceptable and detrimental to patient outcomes to leave frail or acutely ill patients on hard narrow stretchers in noisy crowded rooms where the lights never go out, without privacy, sleep, or bathroom access while they wait hours or days for a hospital bed. Providing the wrong care in the wrong place increases system cost, decreases care quality, and creates chaotic work environments that burn out ED staff. [7] Worse, it compromises the ability of EDs to provide the care they were intended to provide. [4]

Emergency leaders will tell you that EDs have been getting worse for 25 years, and that none of the solutions have worked. Governments have spent hundreds of millions on urgent care centres for low acuity patients, primary care diversion strategies, telephone support lines, public campaigns to discourage ED visits, and even expanded emergency departments. But ED congestion just keeps getting worse.

Why? Because these solutions don’t address the actual causes.

Research shows that the unbridled demand facing EDs is not from too many non-urgent patients, but because of poor access to primary and specialty care, [5] a rising burden of unmanaged chronic disease and—most importantly–a lack of hospital beds for admitted patients. [6-8]

Canada’s Universal Contingency Plan

Canada performs poorly relative to other OECD countries in providing access to primary care, specialists, surgical procedures, and imaging. [6,7] When patients can not find a GP, see a specialist, or have an imaging study, they head for an ED. An Alberta Health Quality Council survey reported that 58% of patients attending the ED did so because it was the only place they could get care when they needed it. With poor access elsewhere, EDs are often the only option; consequently, Canada has the highest rate of ED use among wealthy countries with universal healthcare. [9] A Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Innovation report showed that ED visits are rising much faster than population growth, and without fundamental system change, they will grow an additional 40% in the next two decades. [10]

The emergency medicine credo is that every patient’s concern is important, and that patients cannot be turned away, regardless of their condition. The scope of practice in EDs has expanded well beyond emergent and urgent care. However, attempts to provide unconditional service to nearly everyone have left EDs failing to fulfill their core mission.

EDs are the first or only health access point for many people; [5] they are increasingly a destination for patients with complex and specialty health problems, [4,5] and a referral destination for difficult or marginalized patients who need integrated longitudinal care that should be available in the community. [5] They have become a primary staging area for acutely ill patients, for access to diagnostics, and for hospitalization decisions; all of these make ED practice increasingly complex. [5,11] With the shortage of hospital beds, diagnostic workups that used to require hospitalization are often conducted during an ED visit, and many EDs have developed observation units or long-stay pathways to prevent avoidable admissions.

Inpatient care has become the greatest challenge for emergency departments. Based on the number of admitted patients blocked in ED stretchers and the amount of inpatient care provided by ED nurses, the primary role of most urban EDs now isn’t to provide emergency care, but to serve as holding areas for inpatients awaiting a hospital bed. All these factors have aggravated the crowded conditions that compromise ED patient safety and outcomes. [11,12]

Public Health

ED expectations have expanded in many directions, which are all intuitively good. But they compete for care resources and provider time when emergency care capacity is already overwhelmed, and when EDs are often unable to provide timely emergent care for seriously ill patients. In addition to growing clinical care demands, many believe EDs should provide public health services. [13] The US Public Health Task Force has recommended that EDs conduct alcohol screening and intervention, HIV screening and referral, hypertension screening, pneumococcal vaccination, and smoking cessation counselling. [14]

EDs have a potentially important role as an early/sustained warning system for public health emergencies, including infectious disease outbreaks. Many or most EDs already screen for intimate partner violence, injury risk behaviour, influenza-like illnesses, safe drug use practices, and suicide risk. They frequently provide drug or alcohol counselling, initiate treatment for opioid addiction (opioid agonist therapy), disburse naloxone kits and clean needles, and connect patients to detox programs or targeted therapy. [15] They help patients who are struggling with homelessness and develop programs for frequent ED users. Emergency medicine advocates are now developing sub-specialty training in Social Emergency Medicine (SEM). These programs will develop better ED processes to systematically screen for health-related social needs, connect patients with external agencies, and initiate important community services. They will also develop strategies to reduce social inequity and provide resources that address the social determinants of health.

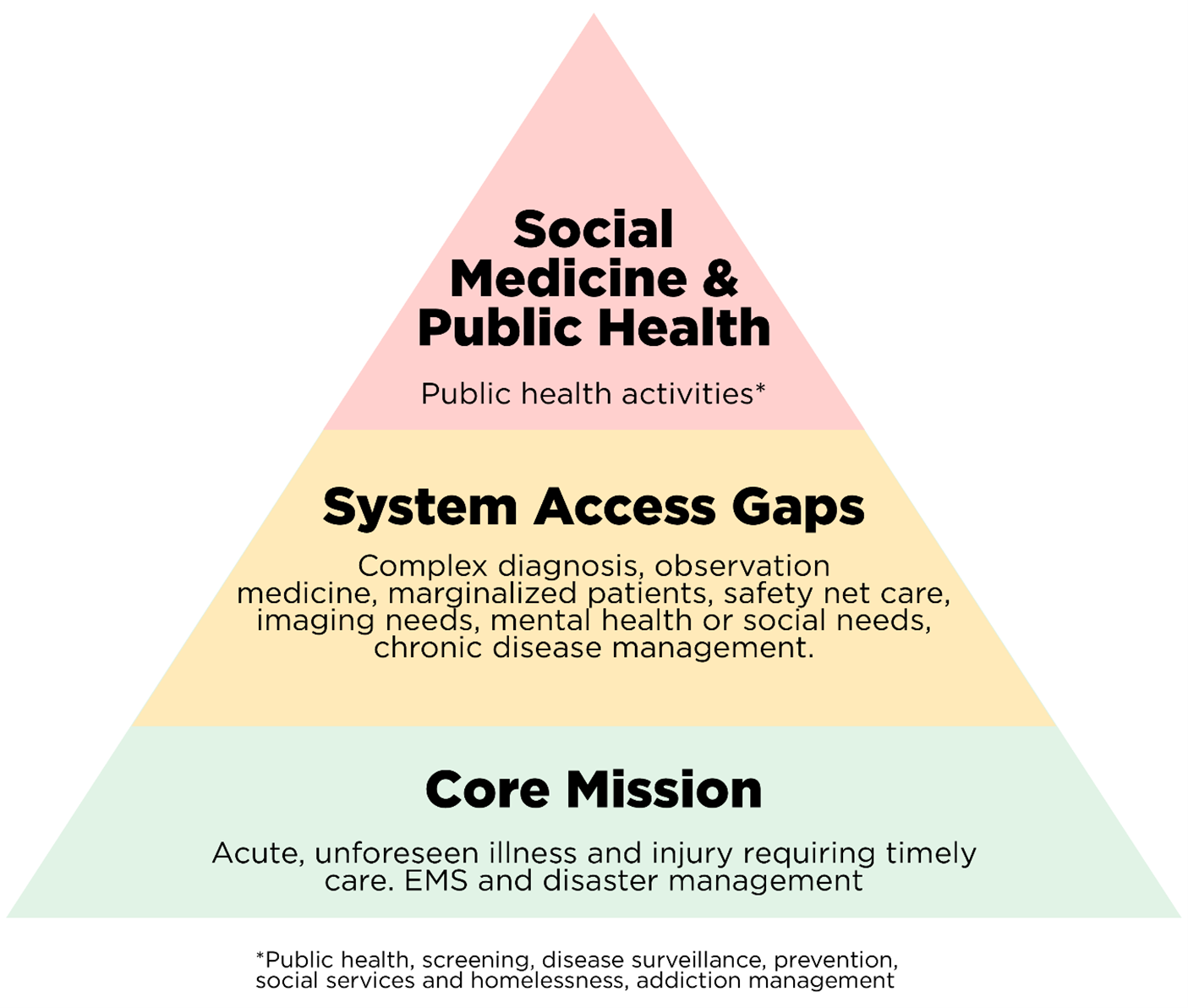

Figure 1. A Hierarchy of Emergency Care

Is Less More?

ED efforts to provide unlimited care have decreased the need for other programs to solve many of the access problems described above. This has enabled other providers to eschew care for unplanned illness and injury, limit off-hours work, avoid inconvenient disruptions in always busy days, and address countless patient needs with an almost magical directive: “Go to the emergency department.” [4] But can EDs fill the care gaps left by other programs and still provide timely, high-quality emergency care? The state of today’s EDs makes the answer a painfully obvious NO. [5]

|

Why, after two decades of deterioration, are emergency departments increasingly overwhelmed? Perhaps they’re doing too much. |

The concept of the ED as healthcare’s universal contingency plan is flawed and dangerous. [4] Ever-increasing volumes, complexity, stress levels, and demands to deliver inpatient care, primary care, non-emergent care, and public health services have become unmanageable. In an ideal world, EDs would continue providing as much care as possible; but if they’re unable to accomplish their primary mission, it may be time to rethink “emergency,” [4] refocus on the core mission in keeping with the specialty’s original intent (Figure 1) and determine how to provide timely high-quality care for patients with acute unforeseen illness and injury.

However, if EDs must cut back, which populations and services should be downprioritized? Re-engineering ED services would require a rational approach that does not put patients at risk, moves care to the most appropriate location, and has some chance of success.

What is Emergency Medicine (EM)?

The Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians (CAEP) has defined EM as a unique set of competencies required for the timely evaluation, diagnosis, treatment, and disposition of patients with injury, illness and behavioural disorders that require expeditious care. [16] The International Federation for Emergency Medicine (IFEM) defines emergency medicine as a practice based on the knowledge and skills required for the prevention, diagnosis, and management of acute and urgent aspects of illness and injury with a full spectrum of undifferentiated physical and behavioural disorders. [17]

The American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) defines EM as a specialty dedicated to the diagnosis and treatment of unforeseen illness or injury that includes the initial evaluation, diagnosis, treatment, and disposition patients requiring expeditious medical, surgical, or psychiatric care. [18] These organizations also state that EM incorporates an understanding of hospital and pre-hospital emergency care systems, and provides readiness for large-scale health emergencies, ranging from local multiple casualty incidents to large-scale pandemics and disasters. All these definitions emphasize acute, unforeseen illness and injury, and this focus has determined the content of EM training programs (to be discussed later in this document).

What About Acute, Less Urgent Care?

Many policymakers believe emergency departments should deprioritize or eliminate less urgent patients who fall into Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale (CTAS) levels 4-5. This belief has led to diversion initiatives to offload EDs, like telephone advice lines and urgent care centres (UCCs). Both provide patients with an alternate care option, but neither have reduced ED volumes or improved emergency care access. [19] Instead, they’ve resulted in an unintended consequence and present a rarely-discussed potential downside: telephone advice lines have provided thousands of nurses the opportunity to move out of direct patient care during a time of profound staffing shortages. And while UCCs do not decompress EDs, they do draw patients and physicians away from primary care. This raises the possibility that these innovations may, in fact, reduce access to the most important and threatened type of care in the system.

The Theory of Constraints

In EDs, emergent care trumps less urgent care, but if the goal is to improve emergency access, low-acuity patients are the wrong population to eliminate. All EM organizational definitions specify that unforeseen low-acuity conditions—particularly injuries—are EM core competencies, and these less urgent patients often require hospital-based diagnostics and expertise. [20,21] Contrary to popular belief, less urgent patients aren’t a significant cause of emergency access block; [21] the reason for this is logical but rarely understood.

The ED’s functional unit and critical resource is the nurse-staffed-stretcher, which is also the primary emergency department constraint (bottleneck). Operations management theory tells us that to maintain flow and reduce care delays, we must increase bottleneck resources (e.g., nurse-staffed stretchers) or unload bottleneck servers (decrease the number of patients placed on stretchers). Diverting low acuity patients away from EDs accomplishes neither, because these patients do not occupy nurse-staffed stretchers. Sadly, ignoring the bottleneck and spending time and money fixing unrelated issues like low acuity patients has not succeeded, and will not succeed in the future. [22]

Less urgent patients also serve an essential function in most emergency departments. Truly emergent cases, our raison d’etre, comprise only a fraction of ED inflow; but EDs must be staffed 24×365 to assure care is available when critical patients do arrive. Less acute patients are a queueable source of work, revenue, and clinical experience for physicians. They fill the gaps between emergencies and make ED staffing economically feasible. In addition, less-urgent care provides return on investment for the high fixed-costs of the department and offers valuable service to the community. Because less urgent patients do not need nurse-staffed stretchers, they do not compete for bottleneck care.

Physicians are a secondary bottleneck, and if the crisis of stretcher availability is solved, they will become the primary bottleneck and main cause of care delays. However, at least in urban settings, physicians are a less constrained resource because it is easier to add physicians than nurse-staffed stretchers. In addition, available physicians can be diverted from treating less-urgent patients when necessary. If we agree that physicians are an important ED bottleneck, the theory of constraints tells us to increase the number of physicians or reduce their workload as much as possible. [22] Less urgent patients who can be processed quickly aren’t a major problem, but complex patients who consume substantial physician time will make the bottleneck worse, and therefore become a priority for diversion to more appropriate care destinations, as illustrated in Table 1.

A decision matrix to identify patients who should or should not be prioritized for ED care might incorporate several factors. First, is the emergency department the right (most appropriate) place for the care in question, and was the ED designed and staffed for this type of care?

Second, does the care in question substantially strain ED bottleneck resources (nurse-staffed stretchers and ED physician time)? Finally, are there unique circumstances that make the ED the only place that can deliver this care? If so, then additional funding, redesign and staff training are probably necessary.

| Right Place?

(Appropriate)* |

ED Stretcher Time

(Primary Bottleneck) |

ED MD Time

(Secondary Bottleneck) |

|

| Care for admitted patients in the ED | No | ++++++++ | ++++ |

| Frail elderly failure to thrive | No | ++++++ | ++++ |

| Complex chronic disease management | No | ++++ | ++++ |

| Exacerbation of chronic mental health problem | No | ++++ | +++ |

| Suicidal ideation | Yes | ++++ | +++ |

| Emergent Care | Yes | +++ | +++ |

| Acute minor injuries | Yes | 0 | + |

| Acute unforeseen low-acuity conditions | Yes | 0 | + |

| Unable to access primary care | No | 0 | + |

Table 1. Decision Matrix: Impact of ED Case Mix Groups on Bottleneck Resources

*The most appropriate ED activities include diagnosis and treatment of acute unforeseen illness or injury, initial evaluation, diagnosis, treatment, and disposition of patients with medical, surgical injury, illness and/or behavioural disorders that require expeditious care.

What Should an Emergency Department Be?

EDs and the services they offer will differ by location, based on community resources and needs. Rural departments differ from urban departments, and inner-city departments differ from community departments. Deprioritizing a non-emergent service does not mean the service should no longer be provided, but rather that external resources, funding, and expertise might be necessary so that the core mission is not compromised. An inner-city ED might, for example, add an adjacent, independently funded mental health addictions (MHA) unit with appropriate expertise, while a community ED might add a similarly-resourced unit focused on the optimal management of elderly patients in their region who are failing.

Recommendations: What Have Emergency Departments Become and What Should They Be?

- EDs should prioritize emergent and urgent care based on the definitions above.

- To do so, they should review their usage and identify non-emergent populations that have the greatest impact on their bottleneck resources, then negotiate or develop more appropriate alternative care options and pathways for these patients. Based on Table 1, top priority populations will include admitted patients waiting for inpatient beds, frail elderly patients (especially those requiring housing, placement, or complex chronic disease management), and patients with chronic mental health and addiction concerns.

References

- Grant K. Canadian nurses are leaving in droves, worn down by 16 merciless months on the front lines of COVID-19. In: The Globe and Mail. 2021. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article- canadian-nurses-are-leaving-in-droves-worn-down-by-16-merciless-months/ Accessed 10 Mar 2023

- Sutherland M, Ibrahim H. Oromocto hospital ER to CLOSE 6 hours earlier each day due to staff SHORTAGE | CBC News 2021; https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/new-brunswick/overnight-er-closure-doctor-shortage-1.6073531#:~:text=’Serious’%20shortage%20of%20staff%20is,doctors’%20mental%20health%2C%20doctors%20say&text=Horizon%20Health%20Network%20will%20be,Tuesday%20because%20of%20staffing%20shortages. Accessed Sep 11, 2023

- Lam P. Staff raise alarm Over ‘exceptionally dangerous’ wait times at St. Boniface Hospital | CBC News. In: CBCnews 2021. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/manitoba/16-hour-wait-time-st-boniface-hospital-staff-shortage-1.6135667. Accessed Sep 11, 2023

- Atkinson P, George, Innes GD. Is less more? Can J Emerg Med 2023; 24:9-11

- Morganti KG, Bauhoff S, Blanchard JC, et al. The Evolving Role of Emergency Departments in the United States. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2013. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR280.html. Accessed Sep 11, 2023

- Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI). How Canada Compares: Results from the Commonwealth Fund 2016 International Health Policy Survey. Ottawa, ON; 2016. https://www.cihi.ca/sites/default/files/document/text-alternative-version-2016-cmwf-en-web.pdf. Accessed Sep 11, 2023

- Berchet C. The Directorate for Employment, Labour and Social Affairs Health Committee of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). Emergency care services: Trends, drivers and interventions to manage the demand. 2015. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/emergency-care-services_5jrts344crns.pdf. Accessed Sep 11, 2023

- Rowe BH, Bond K, Ospina MB, et al. Emergency department overcrowding in Canada: what are the issues and what can be done. Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health. Technology overview. 2006.

- Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI). How Canada Compares: Results from the Commonwealth Fund 2016 International Health Policy Survey. Ottawa, ON; 2016. https://www.cihi.ca/sites/default/files/document/text-alternative-version-2016-cmwf-en-web.pdf. Accessed Sep 11, 2023

- Barr S, Campbell S, Flemons W et al. The Impact on Emergency Department Utilization of the CFHI Healthcare Collaborations and Initiatives: Report to the Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement. 2013; pp. 2–44. https://www.cfhi-fcass.ca/docs/default-source/about-us/corporate-reports/risk-analytica.pdf?sfvrsn=f2ef76ab_2. Accessed Sep 11, 2023

- Pitts SR, Pines JM, Handrigan MT, Kellermann AL. National trends in emergency department occupancy, 2001 to 2008: effect of inpatient admissions versus emergency department practice intensity. Ann Emerg Med. 2012 Dec;60(6):679-686.e3

- Bernstein SL, Aronsky D, Duseja R, et al. Society for Academic Emergency Medicine, Emergency Department Crowding Task Force. The effect of emergency department crowding on clinically oriented outcomes. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16:1-10.

- Gordon JA, Billings J, Asplin BR, et al. Safety net research in emergency medicine. Proceedings of the Academic Emergency Medicine Consensus Conference on The Unraveling of the Safety Net. Acad Emerg Med 2001;8:1024–9.

- Rhodes KV, Gordon JA, Lowe RA, for the SAEM Public Health Task Force. Clinical preventive services: are they relevant to emergency medicine? Acad Emerg Med 2000;7:1036–41.

- Selby S, Wang D, Murray E, et al. Emergency Departments as the Health Safety Nets of Society: A Descriptive and Multicenter Analysis of Social Worker Support in the Emergency Room. Cureus. 2018 Sep 4;10(9):e3247. doi: 10.7759/cureus.3247. Accessed Sep 11, 2023

- McEwen J, Borreman S, Caudle J, et al. Position Statement on Emergency Medicine Definitions from the Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians. Can J Emerg Med. 2018;20:501-506.

- International Federation of Emergency Medicine. IFEM Definition of emergency medicine. Online 2012. Accessed Sep 11, 2023

- Definition of Emergency Medicine. Approved January 2021. https://www.acep.org/globalassets/new-pdfs/policy-statements/definition-of-emergency-medicine.pdf. Accessed Sep 11, 2023

- Lake R, Georgiou A, Li J, et al. The quality, safety and governance of telephone triage and advice services – an overview of evidence from systematic reviews. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017 Aug 30;17:614.

- The Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons. Emergency Medicine Competencies. 2018 pp,1-20. file:///Users/grantinnes/Downloads/emergency-medecine-competencies-e.pdf. Accessed Sep 11, 2023

- Schull MJ, Kiss A, Szalai JP. The effect of low-complexity patients on emergency department waiting times. Ann Emerg Med. 2007 Mar;49(3):257-64

- Goldratt, Eliyahu M. (1990). Theory of Constraints. [Great Barrington, Massachusetts]: North River Press. ISBN 0-88427-166-8.