Section Editors: Ivy Cheng, Alecs Chochinov

Adapting and Evolving in a Changing World

To adapt to a changing world, emergency care systems must continually improve their approach to creating, implementing, and integrating knowledge, within and beyond medicine.

Overview

Chapter 9: Just as we have made recommendations for clinical care, we begin with an exploration of integrating EM research into a broader system. This underlines the importance of tailoring research efforts to the biggest threats to our patients, populations, and planetary health.

Chapter 10: This chapter examines digital health (DH), addressing the potential of new technologies to transform how we communicate with each other, and care for patients virtually. The challenge for us is one of leadership and stewardship, to ensure that DH’s vast potential is realized in a cost-effective way that puts meaningful patient outcomes first and doesn’t drain valuable human resources from our EDs.

Chapter 11: Conflict and differing perspectives are major barriers to collaboration in service of the Quintuple Aim, especially in the ED. Sometimes differing perspectives appear inexplicable, leaving ED care providers frustrated and morally distressed. This chapter, entitled Managing Intergroup Relations, explains that understanding group dynamics and social identity are keys to moving out of our siloed past and collectively achieving better outcomes for patients.

Chapter 12: The EM:POWER project is a prime example of emergency medicine’s potential role in health policy and public affairs. In this chapter, the metaphor of the ED as the passive canary in the coal mine of health system dysfunction is challenged, and replaced with a more empowered construct, in which EM is a leading agent of change.

Chapter 13: Climate change is arguably the biggest health threat of the 21st century; yet many of us have an inadequate understanding of its impact on our patients and health system. This chapter includes a series of recommendations on how as physicians with expert knowledge and global responsibilities, we can prepare ourselves and our EDs for the impact of climate instability, mitigate the effects on our patients, and educate others.

Chapter 14: Boasting the acronym JEDI (not the Star Wars version) this chapter takes us full circle to the core values and principles that must guide us through an uncertain future. It outlines the challenges facing marginalized populations in the ED, with recommendations that focus on achieving a broader understanding of our diverse populations and equitable emergency care for all patients.

Chapter 15: This section ends with an exploration of healthcare strategies and lessons from other countries with liberal democratic values but different health systems. In an increasingly integrated world—and with the health of our patients at stake—it promotes the goal of becoming a true Learning Health System in which we use global knowledge and experience to continually improve.

Chapter 9: Coevolving in the Research and Quality Ecosystem

|

Over 20 years ago, Bégin et al criticized Canada’s fragmented healthcare system, [1] and described it as “a country of pilot projects.”. Proven innovations were rarely implemented, funded, or sustained, resulting in wasted investment, time, and effort. Unfortunately, the same can be said about Canada’s health research infrastructure, as revealed during the COVID-19 pandemic. At the time, many Canadian researchers looked on enviously as the UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR), among others, rapidly pivoted to launch pragmatic trials among Britain’s hospitalized COVID-19 patients. [2]

Within four months of the World Health Organization declaring a pandemic, the NIHR had completed and was reporting preliminary results from the RECOVERY Trial. [3] It determined that dexamethasone reduced 28-day mortality in patients with severe COVID-19. [4] Enabling and funding multicentre trials of the highest calibre rapidly changed practice and recommendations, with an immediate effect on clinical practice in Canada.

RECOVERY’s success was due to a pre-existing research network, the NIHR. In 2006, the UK government created the institute with a mission to support the National Health Service by enabling researchers to conduct cutting-edge research that focused on patient and population needs. [2] The NIHR can pivot its network quickly to focus on a single research question once it passes peer review. When COVID-19 was declared a pandemic, the NIHR simultaneously and rapidly provided funding, data sharing, privacy agreements, national harmonized ethics approval, clinical care and consent for its 176 members to begin the mammoth task of mounting this large-scale trial. [5]

More research networks are being established internationally. For example, the International Severe Acute Respiratory and Emerging Infection Consortium (ISARIC) facilitates clinical trial operations, such as adaptive platform trials, and creates generic protocols like the WHO Clinical Characterisation Protocol. ISARIC’s goal is to create an international infrastructure that can efficiently keep up with the volume of knowledge required during a pandemic of a novel pathogen. This consortium produced the SOLIDARITY trial that globally evaluated interventions to treat COVID-19. [6]

These large multi-national networks likely saved hundreds of thousands of lives during the pandemic. By comparison, Canada lacked sustained research relationships, funding, infrastructure; [7] an efficient nationally harmonized ethics review process; uniform institutional privacy; and legal reviews. There were no flexible, pre-existing data-sharing agreements between the provinces or across the country. If this infrastructure had been available pre-pandemic, we could have rapidly accessed the real-time provincial data needed to accelerate pandemic research that would have provided comprehensive clinical or vaccine coverage information. [8] Further exacerbating our challenges was the emergency medicine workforce shortfall; in addition, the low numbers of Canadian researchers disproportionately impacted research.

Canada simply lacked the efficient processes or infrastructure to fund, launch and rapidly conduct multi-centre observational studies or trials. As a result, many researchers were unable to collect data at the speed necessary for timely clinical and policy decisions. Nor could they easily embed randomized control trials into routine clinical care, the way the NIHR could. [5] Consequently, Canada’s COVID-19 research output was frustratingly slow and lacked impact.

The 2021 commentary by Lamontagne et al. in the Canadian Medical Association Journal echoed the same problems as Bégin et al. had outlined two decades earlier: Canadian research infrastructure is still inefficient, culturally separate from clinical medicine, and fragmented. [9]

This needs to change.

As mentioned in other sections of this report, more investment and mentorship are required to increase the physician per capita ratio. This includes researchers. To avoid the fragmentation of a myriad of small, local topic-based research groups with limited capacity and sustainability, we must develop a pan-Canadian EM network with highly connected provincial (or geographic) nodes. Each should have the resources necessary to coordinate researchers across the EM spectrum, and facilitate inter-specialty, interdisciplinary and interprovincial collaborations. A fully-integrated research network would incorporate all stakeholders, including patients, knowledge users and government, so we can become a community of practice and learning health system.

The pandemic gave us pause for reflection. Shojania asked: “What problems in healthcare quality should we target as the world burns around us?” [10] Although the COVID-19 pandemic was the most widely recognized and urgent healthcare crisis, climate change, [11] the toxic drug crisis, [12] inequality, and systemic racism also require urgent attention through high-quality research and quality improvement. However, as Shojania points out, investment and effort continue to be spent on quality improvement projects and practice guidelines that have minimal outcome. [13][14] He consequently calls for change, and asks that efforts and funding be focused on the most urgent and impactful healthcare issues.

Emergency medicine faces many of the same questions: how can quality improvement and emergency medicine research evolve in our changing healthcare system to address the most urgent needs?

There is growing concern that traditional randomized controlled trials use exclusion criteria that are not applicable to the real-life, complex, and heterogeneous populations that are seen in our Emergency Departments. [15] Trials in Canadian emergency medicine have often limited recruitment to academic sites in urban areas, including those where researchers have personal connections. [16] This may have led to short-changing patients who have waited many years for the delayed results to become available, and in the meantime their well-being was impacted, with lives possibly lost.

Canadian emergency medicine research does, however, have a strong track record in conducting multi-centre cohort studies, [17][18][16][19][20] and the recent development of a pan-Canadian research network in Emergency Medicine, the Canadian COVID-19 Emergency Department Rapid Response Network (CCEDRRN), [21] (set up by NCER, the Network of Canadian Emergency Researchers) [22] builds on this. CCEDRRN has the potential to enable rapid and more efficient implementation of studies across the country, including adaptive trials that offer the potential for us to identify the best treatment for a given health problem.

According to Lamontagne et al., improving Canadian research will require small steps, avoiding traps by using thoughtful design, performing baseline evaluations with benchmarking, evaluating the return on investment, and conducting dialogue with political stakeholders. [9] The CIHR-IHPSR (Canadian Institutes of Health Research – Institute of Health Services and Policy Research) is incorporating these changes by introducing the learning health system (LHS) framework with a community of practice. [23] The LHS connects researchers, healthcare providers, patients, and communities to improve the most relevant healthcare issue. By adopting quality improvement methods, it uses Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles, baseline evaluations and benchmarks to foster continual improvement. [24] British Columbia’s emergency medicine community is re-organizing to become Emergency Care BC (ECBC), an LHS with a knowledge translation network that aims to implement new insights from research and quality improvement. [25]

Canada is developing big data platforms, an essential LHS building block [15] linked to digital health records, which includes external sources outside the healthcare system. In 2020, the Health Data Research Network Canada (HDRN) was created with the mission to use Canadian data to drive improvements in health and health equity. [26] HDRN is made up of 20 Canadian members who represent provincial, territorial, and national organizations with health data holdings. These are comprised of patient-orientated research unit data platforms [27] that can be used by researchers, policymakers and decision-makers. The barriers to rapidly and efficiently accessing multi-jurisdictional data are diminishing but will take time to overcome; yet HDRN is a critical piece of the much-needed pan-Canadian research infrastructure.

Researchers have historically worked in silos, but emergency medicine culture is changing rapidly. Canada’s pandemic-driven research networks include CCEDRRN, NCER, the Long COVID Web, and the Emerging and Pandemic Infections Consortium [28] (one of five national hubs awarded through the Canada Biomedical Research Fund by the Government of Canada), [29][30] Aligned with the Quintuple Aim, [31] emergency medicine research is emphasizing patient-orientated outcomes. [32] In addition to patients, these research collaborations extend across multiple disciplines, methods, and stakeholders, knowledge users, and government. Inspired by the achievements in the UK, resources need extending to expedited, nationally-harmonized ethics review, together with simplified privacy and legal approvals of research studies that include trials. This will require long-term government investment, and further development is needed to ensure sustainable funding.

Emergency medicine research is well-poised to contribute to learning health systems.

Recommendations: Coevolving in the Research & Quality Ecosystem

- Increase funding, training, infrastructure, and planning to support and expand the emergency medicine research workforce.

- Develop a pan-Canadian EM research network with highly connected nodes. Each node should have the resources necessary to coordinate researchers across the EM spectrum and facilitate inter-specialty, interdisciplinary and interprovincial collaborations. This network should incorporate all relevant stakeholders, so we can become an integrated community of practice and learning health system with a focus on achieving the Quintuple Aim.

- Facilitate data-sharing across jurisdictions. Develop a simplified and harmonized national approach to funding, data-sharing, privacy and legal agreements, ethics approval and research consent. Eliminate the need for redundant data, ethics, and privacy processes for multicentre and multi-jurisdictional research.

- Link clinical care, quality improvement, knowledge transfer and knowledge translation using models to move research rapidly to the bedside.

- Emergency medicine research efforts and funding should focus on the most urgent and impactful patient and population healthcare needs.

References

- Bégin M, Eggertson L, Macdonald N. A country of perpetual pilot projects. 2009.

- National Institute for Health and Care Research. National Institute for Health and Care Research.

- Horby P. Dexamethasone for COVID-19: preliminary findings. medRxiv. 2020 Jun;

- RECOVERY CG, Horby P, Lim WS, Emberson JR, Mafham M, Bell JL, et al. Dexamethasone in Hospitalized Patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021 Feb 25;384(8):693–704.

- Murthy S, Fowler RA, Laupacis A. How Canada can better embed randomized trials into clinical care. 2020.

- ISARIC clinical characterisation group. Global outbreak research: harmony not hegemony. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020 Jul;20(7):770–2.

- Hohl CM, McRae AD. Antiviral treatment for COVID-19: ensuring evidence is applicable to current circumstances. CMAJ. 2022 Jul 25;194(28):E996–7.

- McRae AD, Archambault P, Fok P, Wiemer H, Morrison LJ, Herder M, et al. Reducing barriers to accessing administrative data on SARS-CoV-2 vaccination for research. CMAJ. 2022 Jul 18;194(27):E943–7.

- Lamontagne F, Rowan KM, Guyatt G. Integrating research into clinical practice: challenges and solutions for Canada. CMAJ. 2021 Jan 25;193(4):E127–31.

- Shojania KG. What problems in health care quality should we target as the world burns around us. CMAJ. 2022 Feb 28;194(8):E311–2.

- British Columbia Coroners Service. Heat-Related Deaths in B.C Knowledge Update. 2021 Nov 1;

- BC Gov News – Public Safety and Solicitor General. Toxic-drug supply cliams nearly 2,300 lives in 2022: BC Coroners Service. 2023 Jan 31;

- Oxman AD, Thomson MA, Davis DA, Haynes RB. No magic bullets: a systematic review of 102 trials of interventions to improve professional practice. CMAJ. 1995 Nov 15;153(10):1423–31.

- Kwan JL, Lo L, Ferguson J, Goldberg H, Diaz-Martinez JP, Tomlinson G, et al. Computerised clinical decision support systems and absolute improvements in care: meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. BMJ. 2020 Sep 17;370:m3216.

- Foley T. FF. The Potential of Learning Healthcare Systems. 2015 Nov;

- Stiell IG, Sivilotti MLA, Taljaard M, Birnie D, Vadeboncoeur A, Hohl CM, et al. Electrical versus pharmacological cardioversion for emergency department patients with acute atrial fibrillation (RAFF2): a partial factorial randomised trial. Lancet. 2020 Feb 1;395(10221):339–49.

- Stiell IG, Clement CM, Grimshaw J, Brison RJ, Rowe BH, Schull MJ, et al. Implementation of the Canadian C-Spine Rule: prospective 12 centre cluster randomised trial. BMJ. 2009 Oct 29;339:b4146.

- Stiell IG, Nichol G, Leroux BG, Rea TD, Ornato JP, Powell J, et al. Early versus later rhythm analysis in patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 2011 Sep 1;365(9):787–97.

- Perry JJ, Sivilotti MLA, Émond M, Stiell IG, Stotts G, Lee J, et al. Prospective validation of Canadian TIA Score and comparison with ABCD2 and ABCD2i for subsequent stroke risk after transient ischaemic attack: multicentre prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2021 Feb 4;372:n49.

- Thiruganasambandamoorthy V, Sivilotti MLA, Le Sage N, Yan JW, Huang P, Hegdekar M, et al. Multicenter Emergency Department Validation of the Canadian Syncope Risk Score. JAMA Intern Med. 2020 May 1;180(5):737–44.

- Canadian COVID-19 Emergency Department Rapid Response Network (CCEDRRN). [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2023 Feb 6]. Available from: https://www.ccedrrn.com/

- NCER | Better collaboration. Better research. Better care. [Internet]. [cited 2023 Aug 3]. Available from: https://ncer.ca/

- Canadian Institutes of Health Research. CIHR Institute of Health Services and Policy Research Strategic Plan 2015-19.

- Healthy Debate. Understand the Learning Health System.

- BC Emergency Medicine Network. BC Emergency Medicine Network Innovation Program.

- Health Data Research Network Canada. Health Data Research Network Canada.

- Canadian Institutes of Health Research. SPOR SUPPORT Units.

- University of Toronto. EPIC: Emerging and Pandemic Infections Consortium.

- Government of Canada. Award Recipients: Canada Biomedical Research Fund – Stage 1.

- Long COVID Web. Long COVID Web.

- Nundy S, Cooper LA, Mate KS. The Quintuple Aim for Health Care Improvement: A New Imperative to Advance Health Equity. JAMA. 2022 Feb 8;327(6):521–2.

- Archambault PM, McGavin C, Dainty KN, McLeod SL, Vaillancourt C, Lee JS, et al. Recommendations for patient engagement in patient-oriented emergency medicine research. CJEM. 2018 May;20(3):435–42.

Chapter 10: The Future of Digital Health in Emergency Medicine

There are no quick solutions to fixing Canada’s emergency care systems. The reality is that pre- pandemic, our EDs were already overcrowded, patients waited too long, and staff suffered from work stress. [1] Our efforts should not be directed towards turning the clock back to pre- pandemic conditions; rather, we should be focused on developing and implementing a blueprint for our ideal vision of Canada’s future emergency care.

The challenge of getting to that state from where we are is reminiscent of the lost tourist driving through rural Ireland who, when he comes across a farmer in a field, stops and asks him how to get to Dublin. The farmer thinks for a moment and replies, “Going to Dublin, are ya? I would not start from here.” Like the traveller, our starting place may not be the one we choose but is where we are.

There are a few key attributes of a better emergency care system we can work towards. One is meaningful horizontal integration with the rest of the healthcare system, especially primary care and community-based services. Too often in the ED we fly blind, with limited access to a patient’s medical history, care providers and prior investigations. Lacking the information to choose wisely, we choose safely, often ordering tests that would not otherwise be necessary. Similarly, our ability to connect patients for needed care or follow-up after ED discharge is often limited to ‘hope-and-a-prayer’ faxes, transmitted to clinics that may or may not agree to see the patient at some uncertain time in the future.

It is critical to ensure primary care and hospital records are available as part of a shared provincial electronic health record (EHR). [2] Better information sharing could also enable more cost-effective virtual emergency care. In some provinces today, the EHR—if it exists at all—consists only of a viewer with a somewhat random and incomplete collection of records in non-standard formats and timeliness. Accountability to populate EHR systems is also lacking: why not make payment for any publicly-funded healthcare service conditional on the real-time uploading of the clinical record to the EHR in a standard format?

A more integrated digital emergency care system will allow an actual appointment, with a date and time to be booked before the patient leaves the ED. Better yet why not have the patient book it themselves, at a time of their choosing? Such certainty gives both ED provider and patient peace of mind. It can also enable the physician to be more circumspect in ED investigations, knowing there will be a timely follow-up.

Giving patients access to their own health data (which increasingly patients are considered to own) will empower them, give them more control, the ability to manage their care, and help improve outcomes. [2] Access does not need to be one way; patients could also enter their own health data (such as biophysical measurements from wearables), [3] report their symptoms, [4], and outcome measures, [5], which are critical to understanding the important results of ED care.

Finally, we must consider whether those we think of as ‘lost ED tourists’ do not see themselves that way. While some patients would almost certainly seek care elsewhere if alternatives were available and accessible, many others decide to go to the emergency department simply because they believe they need care there. [6] The ED provides a one-stop shop for medical assessment, labs tests, imaging, treatment, and consultation with specialists if needed.[10] Many patients know through personal experience that if they look for care elsewhere, they will likely be sent to the ER anyway. Efforts to focus on ‘real’ emergencies by limiting ED access for so-called inappropriate patients may be destined to fail. [7] Societal expectations may be partly at play; many patients today are used to getting what they need when they need it in the most convenient way (think Amazon, Uber Eats or online banking). The ED as a one-stop-shop may be the health system’s version to this phenomenon. Rather than devising strategies to reverse these trends, like generals planning to fight the last war, perhaps we need to embrace the fact that today’s patients are voting with their feet, and plan accordingly.

This requires re-imagining EDs and building the necessary digital integration with primary and community care. The answer lies in an integrated care network with:

- Improved supports for older persons with frailty.

- Better mental health, addiction, and social services.

- Enhanced access to 24/7 diagnostic testing.

- A full suite of follow-up clinic and services accessible in the ED.

Although this may seem overly optimistic, the truth is innovative examples are increasingly found in our system but remain a patchwork. These range from EDs designed with specific supports for geriatric care, [8][9] pathways for rapid low-barrier access to addiction services, [10] and homeless shelter services integrated with EMS. [11] They must be scaled up and properly funded, with adequately trained members of a diverse healthcare team.

In this journey of health system transformation, all of us—patients and providers alike—are lost travelers, and it’s a long way to Dublin. If we are ever to find our way, we must envision and then build an innovative and integrated future state for emergency care together, using all the tools at our disposal.

Introduction

This chapter aims to map out the current landscape of Digital Health (DH) and Virtual Care (VC) in emergency medicine, identify opportunities and areas of concern, and propose a roadmap where these tools can be effectively embraced as integral parts of our discipline. We take it as self-evident that Canada should continue to advance the meaningful use and adoption of interoperable electronic health records. They enable healthcare providers to access and exchange patient data easily, even between different EHR platforms. For example, computerized provider order entry, where patient data is recorded electronically, allows doctors and healthcare providers to manage care orders such as prescriptions, tests, or treatments.

Below, we focus on VC as well as some emerging technologies that could make a valuable contribution to emergency care.

The Pros and Cons of Digital Health and Virtual Care

Digital Health (DH) encompasses a rapidly advancing collection of technology-enabled tools to improve access to healthcare services and information. The Health Information and Management Systems Society (HIMSS) states that, “Digital health connects and empowers people and populations to manage health and wellness, augmented by accessible and supportive provider teams working within . . . digitally-enabled care environments that strategically leverage digital tools, technologies and services to transform care delivery.” [12]

The World Health Organization (WHO) identifies three key objectives in adopting and scaling up DH to “accelerate global attainment of health and wellbeing”: [13]

- Translating the latest data, research, and evidence into action.

- Enhancing knowledge through scientific communities of practice.

- Systematically assessing and linking country needs with supply of innovations.

Emergency medicine can capably contribute to all three objectives through health services research and implementation in urgent and emergency care domains.

While the potential for DH to transform healthcare has been recognized for several decades, the pandemic precipitated its rapid and massive clinical adoption through Virtual Care services and remote patient monitoring. [14] These practices facilitated the delivery of services, while maintaining social isolation to avoid viral transmission, in compliance with public health policies. The rapidity of DH adoption led to both opportunities [15] and challenges [16] for emergency medicine.

On the one hand, appropriate use of DH and VC can potentially reduce emergency department surges, overcrowding and long wait times. It can provide support and knowledge exchange with colleagues practicing in rural communities, as well as supporting safe discharge and patient self-management through remote monitoring.

On the other hand, flawed design and implementation can result in paradoxical overcrowding of EDs through poor VC case management by health professionals who unnecessarily send patients to the emergency for care. Additionally, VC’s attractive practice and compensation models can draw emergency physicians away from the ED where they are most needed.

It’s essential to purposefully integrate these approaches with traditional emergency medicine service delivery; they can maximize patient safety and convenience, and provide value to the healthcare system. Working towards a future of hybrid care [17] that fulfills the Quintuple Aim will preclude the need to choose between VC or in-person care, but rather encourage the thoughtful combination of both to optimize emergency health service delivery and transform our specialty. [18]

How Can Digital Health Creatively Support EM?

VC is the best-known and most widely used type of digital health in emergency medicine. COVID-19 provided the impetus for many hospital-led VC programs across the country. Their adoption aimed to preserve the healthcare system’s scarce in-person resources, while increasing access to care. Some EDs in Ontario began offering a virtual ED for patients with urgent, but non-life-threatening concerns.

Prior to the pandemic, other emergency VC services included telemedicine to support prehospital care. [19] Patients in BC and Alberta who contacted 811 were triaged by a nurse to attend an ED, and instead were assessed virtually by an emergency physician. The preliminary results were promising, with such physicians safely and cost-effectively diverting a significant number of patients away from the emergency department. [20][21]

Post-pandemic, EDs face overcrowding and long wait times. [22][23] VC can mitigate this, as evidenced by British Columbia’s HEiDi project, which resulted in high patient satisfaction and ED avoidance in lower acuity cases. [20] DH is especially beneficial for healthcare providers if VC is accessed with provincial health records; this offers seamless communication with primary care, along with more transparent and efficient prescribing of diagnostics and therapies.

Patients who need emergency care can benefit from home monitoring and wearable technologies which can be divided into out-of-hospital and in-hospital devices. In the community, these can be paired with smartphone apps that can detect chronic deteriorating health conditions, such as rhythm changes in patients with atrial fibrillation, track changes in spirometry (breathing capacity) in those with lung disease, [24][25] and measure adherence to oral medications. [24] Monitoring medications after discharge from an ED can help patients recovering from acute injury, tracking opioid use for example. [26] Other wearables are specifically designed to act as an overall health safety net, capable of tracking and automatically alerting family and/or healthcare providers about changes in vital signs, and potential falls. [27] In hospital, wearables can monitor patient vital signs, and remote telemetry can gather real-time information on patients who are not in a physical space with monitors. [28] Given worsening crowding problems in Canada’s EDs, this could be particularly beneficial.

In the future, machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI) will play important roles in the ED. While the black box of AI functionality, privacy and medical liability need to be addressed, there is no doubt it can lessen cognitive load and stress by adding a level of predictive modelling to medical decision-making for physicians. [29-31] AI has demonstrated promise in helping to interpret diagnostic imaging and predicting fatal infections like sepsis. It has also been able to assess patients who may suffer a lack of blood flow to the brain and might be at risk of a future cardiac event. Recent leaps in large language processing, such as ChatGPT, suggest AI’s added potential to help provide detailed medical records based on short instructions, without providers having to create a template.

The Challenges of Incorporating DH and VC into Emergency Medicine

|

VC in medicine is well over a century old, [32] and remote communities in Canada have used it to help treat emergency patients well before the COVID-19 pandemic. Nevertheless, there are ongoing challenges that must be addressed, including:

- Data security concerns and privacy.

- Limited physical exam options.

- Health equity concerns, for example the risk of alienating vulnerable groups due to technology and access issues. The homeless, older persons and new immigrant populations are prime examples.

- The perception among many emergency physicians that virtual visits have increased ED visits. A recent study by Kiran et al demonstrated that physicians with a high proportion of VC did not have higher ED visits for their patients than those who provided the lowest levels of virtual care. [33] Further study, addressing the full spectrum of ED-UC VC, is needed.

- Workforce issues, including those in which the limited resource of emergency physicians is drawn to less onerous, but less essential work in certain VC settings

- The loss of in-person care, which could adversely affect the culture of emergency medicine and the benefits accrued from face-to-face care contact between doctor and patient.

The Canadian Medical Protective Association (CMPA) has set out the following additional challenges that must be considered when providing VC: [34]

- Risk of exacerbating the fragmented approach to healthcare across Canada.

- Inconsistency in standards and guidelines regarding when it is reasonable to use virtual care.

- Lack of proper infrastructure and training on the various modalities of virtual care.

- Lack of access to secure virtual care platforms.

A major concern is the private involvement in DH development. While innovation is welcome and fuelled by entrepreneurship, careful guardrails are needed to ensure that private interest does not influence the processes or privacy of care. [35,36] Precious resources must be focused on safe public delivery of ED care—and not on DH privatization.

Visioning the Future with Digital Emergency Medicine

The need for emergency medical services continues to rise, resulting in a shortage of resources and an overwhelming workload for EM practitioners. The situation has been extensively described elsewhere in this report overcrowded EDs, long wait times, and limited availability of essential supplies and equipment. DH includes a set of invaluable tools to help emergency care systems scale up services, improve patient outcomes, reduce mortality and morbidity, and better manage data to deliver healthcare. [37] DH must not replace in-person care, with its attendant tangible and intangible benefits, but can augment and complement its overall provision.

DH should also be considered an adjunct to human resources. ED staff can actively participate to integrate and implement DH into the clinical workflow by identifying the “why, what, how” of DH projects and prioritize them in specific purposes. ED leaders are encouraged to participate in DH research and implementation in an integrated manner within the community healthcare system (hospital, primary care, mental health program, etc.) as well as within provincial, national, and international networks.

Conclusion

Digital and technological innovations are scaling rapidly, and medicine continues to adopt and implement the best of them into every specialty. In a future not too far from now, DH will transform medicine. Metabolomic (the study of small molecules in a cell or tissue) and genomic (gene-related) findings mean treatments can be customized to a person’s genetic makeup. This will change the way we treat patients, choose and tailor pain medications, antibiotics, or anti-depressants for instance. AI will accelerate notetaking and prescribing, [38] as well as helping to monitor patients, and detect diseases in early stages. These areas of research will open doors to personalized diagnostics and treatment. Emergency medicine leaders must be proactive by integrating these technologies to enable the best possible patient outcomes.

DH is an inevitability in emergency care. The question is not whether DH will be adopted, but rather how technology can help forge a path to achieve the Quintuple Aim of improved patient experience, better population outcomes, lower costs, an empowered workforce, and health equity for all Canadians. The latter two are worth reiterating: if DH proves a burden to providers, and inaccessible to our most vulnerable, this technological revolution will be met with resistance rather than acceptance. It’s therefore imperative to understand both the vast potential and the pitfalls of DH, so we can choose future applications and resource allocations wisely.

Recommendations for Digital Health in the EM

- EM leaders in Canada must work together with all stakeholders to build a DH record system which allows access for both patients and direct healthcare providers.

- To achieve this, health information systems should be integrated at regional, as well as F/P/T levels.

- Emergency physicians must embrace leadership and stewardship roles in DH, to ensure that the most effective initiatives are supported and that precious public resources are not diverted to frivolous ventures or privatization of DH.

- EM specialists should assume key roles in the regulation of DH applications in healthcare by way of legislation and government policies.

- Departments of EM and EM professional societies should collaborate in national and global translational (practically-oriented) research to best apply digital heath’s strengths to EM’s needs.

- EM training and professional development should be reviewed to ensure core competencies related to the use of DH are taught.

- Digital health should be a focus of quality improvement initiatives at hospital EDs and academic ED departments.

- Appropriate consideration should be given to the varying levels of digital literacy, access, and education in Canada’s populations to help prevent barriers to the equitable and fair implementation of digital ED health. [39,40]

References

- News · CBC. CBC. 2019 [cited 2023 Sep 6]. Wait times at Ontario hospitals climbed to record high this summer, data shows | CBC News. Available from: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/june-hallway-medicine-data-1.5271281

- Tapuria A, Porat T, Kalra D, Dsouza G, Xiaohui S, Curcin V. Impact of patient access to their electronic health record: systematic review. Inform Health Soc Care. 2021 Jun 2;46(2):192–204.

- Dinh-Le C, Chuang R, Chokshi S, Mann D. Wearable Health Technology and Electronic Health Record Integration: Scoping Review and Future Directions. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2019 Sep 11;7(9):e12861.

- Cancer Care Ontario [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2023 Sep 6]. Patient Reported Outcomes & Symptom Management Program. Available from: https://www.cancercareontario.ca/en/cancer-care-ontario/programs/clinical-services/patient-reported-outcomes-symptom-management

- Vaillancourt S, Cullen JD, Dainty KN, Inrig T, Laupacis A, Linton D, et al. PROM-ED: Development and Testing of a Patient-Reported Outcome Measure for Emergency Department Patients Who Are Discharged Home. Ann Emerg Med. 2020 Aug;76(2):219–29.

- Vogel JA, Rising KL, Jones J, Bowden ML, Ginde AA, Havranek EP. Reasons Patients Choose the Emergency Department over Primary Care: a Qualitative Metasynthesis. J Gen Intern Med. 2019 Nov;34(11):2610–9.

- Atkinson P, McGeorge K, Innes G. Saving emergency medicine: is less more? CJEM. 2022 Jan;24(1):9–11.

- News · CBC. CBC. 2022 [cited 2023 Sep 6]. Why a first-of-its-kind seniors emergency care centre could be an important test for Ontario | CBC News. Available from: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/seniors-emergency-care-centre-toronto-western-hospital-1.6685550

- Vermond K. Your Health Matters. 2020 [cited 2023 Sep 6]. ED One Team fights “hallway medicine.” Available from: https://health.sunnybrook.ca/magazine/sunnybrook-magazine-fall-2020/ed-one-team-hallway-medicine/

- Rapid Access Addiction Medicine Clinic – Addiction Services – Toronto – Sunnybrook Hospital [Internet]. [cited 2023 Sep 6]. Available from: https://sunnybrook.ca/content/?page=bsp-rapid-addiction-medicine

- Toronto [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2023 Sep 6]. New hospital program helps Toronto’s homeless, cuts ambulance offload time. Available from: https://toronto.ctvnews.ca/new-hospital-program-helps-toronto-s-homeless-cuts-ambulance-offload-time-1.6209499

- MobiHealthNews [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2023 Sep 6]. HIMSS launches new definition of digital health. Available from: https://www.mobihealthnews.com/news/himss-launches-new-definition-digital-health

- Digital health [Internet]. [cited 2023 Sep 6]. Available from: https://www.who.int/health-topics/digital-health#tab=tab_1

- Tuckson RV, Edmunds M, Hodgkins ML. Telehealth. N Engl J Med. 2017 Oct 19;377(16):1585–92.

- Ho K. Virtual care in the ED: a game changer for the future of our specialty? CJEM. 2021;23(1):1–2.

- Innes G. Fast food medicine. Canadian Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2023;1–2.

- Licurse A, Fanning K, Laskowski K, Landman A. Balancing Virtual and In-Person Health Care. Harvard Business Review [Internet]. 2020 Nov 17 [cited 2023 Sep 6]; Available from: https://hbr.org/2020/11/balancing-virtual-and-in-person-health-care

- Disruptive and Sustaining Innovation in Telemedicine: A Strategic Roadmap | NEJM Catalyst [Internet]. [cited 2023 Sep 6]. Available from: https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.21.0311

- Amadi-Obi A, Gilligan P, Owens N, O’Donnell C. Telemedicine in pre-hospital care: a review of telemedicine applications in the pre-hospital environment. Int J Emerg Med. 2014 Jul 5;7:29.

- Ho K, Lauscher HN, Stewart K, Abu-Laban RB, Scheuermeyer F, Grafstein E, et al. Integration of virtual physician visits into a provincial 8-1-1 health information telephone service during the COVID-19 pandemic: a descriptive study of HealthLink BC Emergency iDoctor-in-assistance (HEiDi). Canadian Medical Association Open Access Journal. 2021 Apr 1;9(2):E635–41.

- Services AH. Alberta Health Services. [cited 2023 Sep 6]. Virtual MD connects Health Link callers directly to physicians. Available from: https://www.albertahealthservices.ca/news/Page16756.aspx

- Huffman A. From “A Campfire to a Forest Fire”: The Devastating Effect of Wait Times, Wall Times and Emergency Department Boarding on Treatment Metrics. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2023 Jan 1;81(1):A13–7.

- Kenny JF, Chang BC, Hemmert KC. Factors Affecting Emergency Department Crowding. Emergency Medicine Clinics of North America. 2020 Aug 1;38(3):573–87.

- Chai PR, Carreiro S, Innes BJ, Chapman B, Schreiber KL, Edwards RR, et al. Oxycodone Ingestion Patterns in Acute Fracture Pain with Digital Pills. Anesth Analg. 2017 Dec;125(6):2105–12.

- Li T, Divatia S, McKittrick J, Moss J, Hijnen NM, Becker LB. A pilot study of respiratory rate derived from a wearable biosensor compared with capnography in emergency department patients. Open Access Emerg Med. 2019;11:103–8.

- Ho K, Novak Lauscher H, Cordeiro J, Hawkins N, Scheuermeyer F, Mitton C, et al. Testing the Feasibility of Sensor-Based Home Health Monitoring (TEC4Home) to Support the Convalescence of Patients With Heart Failure: Pre–Post Study. JMIR Form Res. 2021 Jun 3;5(6):e24509.

- Darwish A, Hassanien AE. Wearable and Implantable Wireless Sensor Network Solutions for Healthcare Monitoring. Sensors (Basel). 2011 May 26;11(6):5561–95.

- Miller K, Baugh CW, Chai PR, Hasdianda MA, Divatia S, Jambaulikar GD, et al. Deployment of a wearable biosensor system in the emergency department: a technical feasibility study. Proc Annu Hawaii Int Conf Syst Sci. 2021 Jan 5;2021:3567–72.

- Kirubarajan A, Taher A, Khan S, Masood S. Artificial intelligence in emergency medicine: A scoping review. Journal of the American College of Emergency Physicians Open. 2020;1(6):1691–702.

- Artificial intelligence and machine learning in emergency medicine: a narrative review – Mueller – 2022 – Acute Medicine & Surgery – Wiley Online Library [Internet]. [cited 2023 Sep 6]. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/ams2.740

- Grant K, McParland A, Mehta S, Ackery AD. Artificial Intelligence in Emergency Medicine: Surmountable Barriers With Revolutionary Potential. Ann Emerg Med. 2020 Jun;75(6):721–6.

- Aronson SH. The Lancet on the telephone 1876-1975. Med Hist. 1977 Jan;21(1):69–87.

- Kiran T, Green ME, Strauss R, Wu CF, Daneshvarfard M, Kopp A, et al. Virtual Care and Emergency Department Use During the COVID-19 Pandemic Among Patients of Family Physicians in Ontario, Canada. JAMA Netw Open. 2023 Apr 28;6(4):e239602.

- CMPA [Internet]. [cited 2023 Sep 6]. CMPA – White paper—Integrating virtual care in practice: Medico-legal considerations for safe medical care. Available from: https://www.cmpa-acpm.ca/en/research-policy/public-policy/integrating-virtual-care-in-practice–medico-legal-considerations-for-safe-medical-care

- Grande D, Luna Marti X, Feuerstein-Simon R, Merchant RM, Asch DA, Lewson A, et al. Health Policy and Privacy Challenges Associated With Digital Technology. JAMA Network Open. 2020 Jul 9;3(7):e208285.

- Horn R, Kerasidou A. Sharing whilst caring: solidarity and public trust in a data-driven healthcare system. BMC Medical Ethics. 2020 Nov 3;21(1):110.

- Abernethy A, Adams L, Barrett M, Bechtel C, Brennan P, Butte A, et al. The Promise of Digital Health: Then, Now, and the Future. NAM Perspect. 2022:10.31478/202206e.

- Choudhary G. mint. 2023 [cited 2023 Sep 6]. GPT-4 simplifies medical writing for prescriptions and notes. Know here’s how. Available from: https://www.livemint.com/technology/apps/gpt4-simplifies-medical-writing-for-prescriptions-and-notes-know-here-s-how-11679379420629.html

- Hyman A, Stacy E, Mohsin H, Atkinson K, Stewart K, Lauscher HN, et al. Barriers and Facilitators to Accessing Digital Health Tools Faced by South Asian Canadians in Surrey, British Columbia: Community-Based Participatory Action Exploration Using Photovoice. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2022 Jan 13;24(1):e25863.

- Whitelaw S, Pellegrini DM, Mamas MA, Cowie M, Van Spall HGC. Barriers and facilitators of the uptake of digital health technology in cardiovascular care: a systematic scoping review. Eur Heart J Digit Health. 2021 Mar;2(1):62–74.

Chapter 11: Managing Intergroup Relations

Conflict among the programs, sites, professions, and specialties that provide care impairs how systems function, and prevents a shared vision for change from developing. Unfortunately, such conflict is pervasive in healthcare. [1] It certainly appears in the emergency department (ED), where a diffuse patient population and complex interconnections with other departments create prime conditions for strife about who “owns” which patient.

A classic study documented how ED patient charts—supposedly repositories of objective information—were battlegrounds of inter-specialty competition and sniping, with potentially devastating consequences for patients caught in the crossfire. [2] The picture is hardly prettier at the system level, with its ubiquitous silos among professions, programs, sites, and sectors, not to mention between clinicians and management. [3]

Why, then, are intergroup relations so problematic, and what can we do about it?

Getting to the Root Cause

To start with, this isn’t an interpersonal issue that can be solved by sending everyone for training in communication skills: the problem doesn’t reflect lack of skill, but rather the active expression of strongly-held social identities. [2] These are the parts of people’s identity that come from being a member of a group or category, such as one’s nationality, gender, profession, or department. While there are many formal and folk theories of how groups operate, social identity theory [4,5] outperforms with its comprehensiveness, theoretical coherence, and robust evidence base. [6] It provides a broad, multifaceted approach to understanding how people interact with others within and between groups.

Decades of research have illustrated the powerful force of social identity; even meaningless groups assigned in a lab can influence the way people treat in-group vs. out-group members. [4-6] In reality, of course, social identities are not empty labels, but include meaningful identity content (such as group-defining characteristics, norms, and values) which makes them all the more powerful. [7]

Why do we categorize ourselves and others? Doing so serves two deep needs: the cognitive need to simplify the social world, and the emotional need to identify with something greater than ourselves. [4,5] In other words, social identity isn’t going away. Nor should it. Although negative outcomes, such as prejudice, discrimination, and conflict come to mind, shared identity can also be the wellspring of collaboration, altruism, and solidarity. [8] The question is not how to get rid of social identities (we can’t) but how to manage them so that their effects are positive instead of negative.

The most obvious solution is to urge everyone to abandon narrow distinctions and transfer their identification to one all-encompassing group. After all, aren’t we all here for the patient? We see how when a crisis strikes, say, after a natural disaster, or at the height of the pandemic, everyone unites behind a common cause, putting aside intergroup rivalries—only to take them up again when the crisis abates. Why can’t we all simply identify as healthcare providers, or indeed, as members of humanity?

It’s not that simple. For one thing, we are wired to pay attention to intergroup contrast. [5] Under most circumstances, an abstract, all-inclusive category provides very little information about the social world. It also tends to have limited emotional resonance; it is hard to get excited about who we are if nothing distinguishes us from anyone else. All things being equal, groups with high distinctiveness (owing to their small size, unique identity content, and/or alignment with meaningful physical boundaries) are most likely to be significant to us, as observed both within and outside healthcare. [3,5] So although a crisis can temporarily override intergroup distinctions, we should not be surprised when they surface again.

Additionally, people react unfavourably to the prospect of a valued identity being removed or altered. [8] Unfortunately, identity threat, as it is called, can easily be triggered by well-meaning appeals to put aside intergroup differences in favour of the common good, [1.9] especially if they come from an outgroup. This is even more likely if the subtext is “we’d all get along if only you people would be more like us,” an appeal for unity that appears more often than you’d think. [10] But the problem cannot be remedied merely by crafting better messages: any perceived challenge to a valued group’s existence, status, distinctiveness, or norms—essentially any attempt to get people to work together differently—can trigger identity threat, and spark resistance.

So how can change ever succeed?

Strategies that Work

Change can take place by working through social identities, not against them. [1,6] A diverse body of literature has uncovered a sequence dubbed reinforce-redefine-replace. [10] Counterintuitive as it may seem, agents of change must start by reinforcing existing identities, reassuring members that the groups and group-defining values they cherish will not disappear. Once these identities are secure and not under threat, members may entertain ideas that somewhat redefine the group and/or its relationship to others, so long as a strong link to the past is retained. Eventually, a new conception of group identity, or of an intergroup relationship, may come to replace the old.

The literature offers diverse examples of reinforce-redefine-replace sequences, such as the following:

Building a Mosaic Identity

Several organizations struggling to improve staff engagement have found the ASPIRe (Actualizing Social and Personal Identity Resources) model [9] helpful. After a phase of discovering what sub-groups (e.g., profession, department) are locally meaningful, employees meet in identity-based subgroups (reinforce) before coming together to identify commonalities (redefine) and finally set shared goals (replace).

This process seeks to build a mosaic identity that recognizes each subgroup’s uniqueness as well as its contribution to a larger whole. Separate from tests of the ASPIRe model, the theme of mosaic identity has emerged strongly from case studies of organizations that have achieved a high degree of interprofessional collaboration, such as the Dana Farber Cancer Institute. [10]

Reinforcing Another Group’s Identity

Conflict between managers and physicians is common in healthcare, and many hospitals have tried to repair strained relationships. Leaders’ efforts often begin with overtures to reopen communication with physicians and build one-on-one relationships, but then what? The most effective next steps are typically those that reinforce physician identity, for instance by supporting their ability to act as a group. This might include encouraging the formation of a physician advisory board and compensating members for their time; upholding physician norms such as keeping meetings brisk and action-oriented; and using language that belongs in a clinical setting rather than a corporate boardroom. [12,13] Such actions can help advance the intergroup relationship to a point that allows cooperation around specific objectives (redefine), and eventually, the development of shared goals and structures (replace). However, this process cannot be forced or rushed. One hospital CEO, emboldened by the success of early efforts to de-escalate tension, decided to leapfrog over stages, and moved quickly to ask everyone to create a common agreement for working together. Conflict immediately flared again, and the CEO was back on the phone with the social identity consultant, who backed away slowly. [12] Even a smaller leap from interpersonal strategies to the redefine phase has shown evidence of backfiring. [11]

Honouring the Past

Back in the 1950s, nursing textbooks would praise Florence Nightingale as the physician’s loyal helper, a subservient role considered part of nursing identity. As the decades advanced, gender roles changed and nursing roles along with them, but the textbooks could not very well abandon their pioneer. So, they did not. They just let the idea of subservience quietly slip away, while focusing on aspects of nursing identity that did not change, such as being nurturing. The authors also began to introduce new aspects that were more consistent with equal status, such as patient advocacy, a commitment to holism, and eventually, the possession of a distinct body of scientific knowledge. And who did they position as the scientific, holistic patient advocate? You guessed it: Florence Nightingale. [14]

At no point did the textbooks explicitly break with the past; rather, they emphasized a sense of continuity with history to legitimize new features of this identity. A similar process over a shorter time frame is seen in studies of physicians who participate in new models of primary care. In this case, their identity shifts from autonomous expert to head of team by gradually incorporating new elements that are perceived as congruent with the old. [15]

Putting it Together

The literature also suggests that identity mobilization works in alternation with practical, concrete changes to the working environment. [1] The purpose of reinforcing and redefining identities is to build enough support to implement practical changes; once implemented, such change can stimulate further identity reshaping, enabling a more extensive shift in the next cycle.

Education and training are particularly important settings for social identity management. Interprofessional education programs have demonstrated positive impacts on both learners and patients and should continue to be expanded and refined. [16] It’s also crucial that residency programs include opportunities for productive interaction among specialties, for instance, by ensuring that internal medicine residents rotate through the ED. Collaborative experiences during the process of forming a person’s identity can promote identification with a group beyond one’s own profession or specialty, and at the same time establish teamwork as part of one’s professional identity.

This chapter has focused on managing the internal dynamics of the healthcare system. Of course, social identity theory has much broader applications. Better understanding of identity processes could enhance our efforts to combat racism in healthcare, and to promote EDI more generally. Social identity thinking may also help the health community engage more effectively with the public on health policy and public health issues.

Conclusion

There is no magic bullet when it comes to implementing system change: no matter how carefully social-identity-management strategies are selected and calibrated, the process remains difficult, and the outcome uncertain. Nonetheless, it can be helpful to block off time to examine potential strategies through this lens. Understanding how social identities work—in particular, the problem of identity threat and the promise of reinforce-redefine-replace sequences—can help change agents increase the chance of success.

References

- Kreindler SA, Dowd D, Star N, Gottschalk T. Silos and social identity: The social identity approach as a framework for understanding and overcoming divisions in healthcare. Milbank Q 2012; 90(2): 347- 374.

- Hewett DG, Watson BM, Gallois C, Ward M, Leggett BA. Communication in medical records: intergroup language and patient care. Journal of Language and Social Psychology; 2009; 28(2):119- 138.

- Kreindler SA, Hastings S, Mallinson S, Brierley M, Birney A, Tarraf R, Winters S, Johnson K. Managing intergroup silos to improve patient flow. Health Care Manage Rev 2022; 47(2): 125-132.

- Tajfel H, Turner JC. An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In G. Austin, & S. Worchel (Eds.), The social psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 33-47). Monterey: Brooks/Cole; 1979.

- Turner JC, Hogg MA, Oakes PJ, Reicher SD, Wetherell MS. Rediscovering the social group: A self- categorization theory. Oxford: Blackwell; 1987.

- Haslam SA. Making good theory practical: Five lessons for an Applied Social Identity Approach to challenges of organizational, health, and clinical psychology. British Journal of Social Psychology 2014; 53(1): 1-20.

- Ellemers NE., Spears R., Branscombe NR. (Eds.). Social identity: context, commitment, content. Oxford: Blackwell; 1999.

- Ellemers N, Spears R, Doosje B. Self and Social Identity. Annual Review of Psychology 2002; 53, 161- 186.

- Haslam SA, Eggins RA, Reynolds KJ. The ASPIRe Model: Actualizing social and personal identity resources to enhance organizational outcomes. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 2003; 76: 83-113.

- Kreindler SA. The politics of patient-centred care. Health Expect 2015; 18(5): 1139-50

- Kreindler SA, Struthers A, Metge CJ, Charette C, Harlos K, Beaudin P, Bapuji SB, Botting I, Francois J. Pushing for partnership: Physician engagement and resistance in primary care renewal. J Health Org Manag 2019; 33(2): 126-140

- Fiol CM, Pratt MG, O’Connor EJ. Managing intractable identity conflicts. Academy of Management Review 2009; 34(1): 32-55.

- Kreindler SA, Larson BK, Wu FM, Gbemudu JN, Carluzzo KL, Struthers A, Van Citters AD, Shortell SM, Nelson EC, Fisher ES. The rules of engagement: Physician engagement strategies in intergroup contexts. J Health Org Manag 2014; 28(1): 41-61.

- Goodrick E, Reay T. Florence Nightingale endures: Legitimizing a new professional role identity. Journal of Management Studies 2010; 47(1): 55-84.

- Reay T, Goodrick E, Waldorff S, Casebeer A. Getting leopards to change their spots: co-creating a new professional role identity. Academy of Management Journal 2016; 60(3): 1043–1070.

- Reeves S, Fletcher S, Barr H, Birch I, Boet S, Davies N, McFayden A, Rivera J, Kitto S. A BEME systematic review of the effects of interprofessional education: BEME Guide No. 39. Medical Teacher 2016; 38(7): 656-668. Emergency Medicine’s Future Role in Health Policy and Public Affairs.

Chapter 12: Emergency Medicine’s Future Role in Health Policy and Advocacy

|

Background

Emergency department closures and crowding, with their potential lethal consequences, are garnering media attention across the country. [2] Building on shared national goals, it makes sense to have a coordinated effort to address these issues, and that is the purpose of this report, clearly articulated in our overarching recommendations.

But it will take more than words—however well-intentioned and informed—to produce meaningful change. That is where engagement in policy, public affairs and advocacy begins.

Healthcare in Canada is largely under provincial jurisdiction. The Canada Health Act provides conditions for federal health transfers to the provinces for hospital and medical care, but each province organizes and operates its own system within the very broad parameters of the Act. [1] Despite regional differences, however, healthcare shortfalls are widespread across Canada and similar in nature from province to province.

The Role of the Emergency Department in a Dysfunctional Health System

EDs fulfill a unique but increasingly difficult role in the health system. Through the patients they see, emergency physicians are witness to a host of social and health system ills that give them unique insights into the system and its failings.

The oft-used metaphor of the ED as the canary in the coal mine [3] is unfortunate, as it paints a picture of emergency staff as passive and reactive. The EM:POWER message is that ED professionals have the agency, credibility, and experience to be proactive, because we work at a critical healthcare intersection, the junction between community, prehospital, primary, and acute care. We provide services ranging from resuscitation to public health to geriatrics. EDs are the decision point for most hospitalizations, a gateway to urgent imaging, surgery, specialty care and critical care.

We are the only open door for many complex and marginalized patients and for growing numbers of those unable to access the right care in the right place. ED providers have a unique system perspective, a view of many possible pathways, including promising future directions. In that new construct, emergency physicians can be powerful agents of change, observing, anticipating, and responding to the health issues of the day, with a voice that resonates across the entire medical system.

How Can this Report be Used to Create Health Policy?

This report invites healthcare stakeholders to recognize the importance of EDs as barometers of overall system health, and emergency physicians as repositories of health system expertise. However, for any system to be functional, there must be an ever-present focus on purpose. We believe the Quintuple Aim [4] is the best framework to guide healthcare policy, and we’ve used it to inform the development of the EM:POWER report and recommendations.

Detailed action plans that cater to population needs will be essential to ensure the report has ongoing value. These are largely the purview of provincial health authorities and Emergency Care Clinical Networks [5] which we recommend be established to lead and coordinate clinical services and HHR planning. The report itself provides the framework and flexibility to allow local autonomy and decision-making; but the federal government holds a key coordinating role to connect provincial/territorial leadership from across Canada to help address common challenges. These include crowding, closures, and Health Human Resources (HHR) as well as to facilitate the establishment of accountability frameworks and disaster preparedness.

It is important for decision-makers to realize that the journey to a more cohesive and functional system will be daunting, take time, and will not conform to political cycles and exigencies. Strategies arising from this report must be based on a clear, depoliticized, long-term vision, with short, medium, and long-term objectives. This avoids the one problem, one solution trap that ultimately fails and reverts to emergency backlogs.

The Practice of Emergency Medicine and CAEP Advocacy

Advocacy can be an important part of an emergency career, giving a sense of agency and connection to the larger problems that underlie our daily work lives. Organized emergency medicine can provide a powerful platform for addressing societal needs that manifest first or frequently in our EDs.

Beyond the current focus on crowding and closures, CAEP has also articulated positions on topics such as violence in the ED, opioid use disorder, gun control, intimate partner violence, homelessness, and care of the elderly. In addition, our organization is currently leading advocacy for national red flag laws to protect those at imminent risk of harm, such as victims of intimate partner violence, those with mental health disorders and the elderly. [8] These topics are linked by way of their prevalence in vulnerable populations or those suffering health inequities. All visit our emergency departments, often feeling they have no other recourse.

During the first year of the pandemic, nimbleness was the order of the day, and a small kitchen cabinet of CAEP executive and public affairs leadership developed 18 position statements and communiques related to COVID-19, along with hosting over 40 media events. [7] This work was essential to preserving and protecting emergency staff, and to ensuring our patients continued to have access to emergency care.

In a post-pandemic world, access block, and the resulting negative impact on patient health and mortality will dominate the discussion for the foreseeable future. [8] While ED crowding has become an international problem, as we emerge from the pandemic this has been particularly chronic and intractable in Canada. The problem is covered extensively elsewhere in this report, but the necessary changes will only come about if we have effective emergency medicine champions to engage with planners and decision- makers, within and beyond medicine.

Training Future Leaders in Public Affairs

As the EM:POWER Task Force formulated this report, we were frequently asked, “Who is this report’s target audience? Those providing care in the ED or those outside it?” While our proximate audience is within healthcare, the ultimate drivers of change are those who consume it, the citizens of Canada, our patients. They will demand system improvement through their publicly- elected officials. The importance of public affairs to emergency care thus becomes self-evident.

Succession planning is important in any political sphere, and this is no different. There are notable emergency physician public affairs thought leaders, who for decades have increased emergency medicine’s profile and advanced its priorities. However, there is little to no formal education in public affairs within EM training programs, even though those in the ED are inextricably linked to, and impacted by, health policy. EM training programs would therefore do well to include such training within a larger Health System Sciences curriculum [9] to nurture the next generation of public affairs leaders.

Recommendations for Emergency Medicine’s Future Role in Health Policy and Public Affairs

- CAEP should actively engage with federal /provincial/territorial ministries, health policy experts and medical organizations to promote the report and its recommendations.

- Provincial ministries of health should fund and enable Emergency Care Clinical Networks (ECCN) and integrate them with the broader Healthcare system governance structure.

- The Provincial/Territorial Council of Deputy Ministers of Health should establish and fund a National Emergency Care Council to provide expert advice to each provincial ECCN; connect/coordinate provincial leadership from across Canada to help address key challenges (e.g., crowding/closures/human health resources); and assist in the development of accountability networks and disaster preparedness.

- CAEP should continue alliances with organizations who share their goals and objectives such as CMA (Canadian Medical Association), NENA (the National Emergency Nurses Association), IFEM (the International Federation for Emergency Medicine), the Society of Rural Physicians of Canada (SRPC), and the Coalition for Gun Control.

- EM:POWER’s framework recommendations should be presented to provincial and regional ECCNs as a basis for system redesign at a more granular level, based on local population health needs and resources.

- EM training programs should include public affairs as part of a Health Systems Science curriculum, to educate residents and nurture the next generation of public affairs leaders.

References

- The Canada Health Act: An Overview [Internet]. [cited 2023 Sep 20]. Available from: https://lop.parl.ca/sites/PublicWebsite/default/en_CA/ResearchPublications/201954E

- Contact AFCNNMCF|. CTV News. 2023 [cited 2023 Sep 20]. Three stabbed teens were driven from a party to a nearby hospital, only to find that the ER was closed. Their story is one of many. Available from: https://www.ctvnews.ca/health/three-stabbed-teens-were-driven-from-a-party-to-a-nearby-hospital-only-to-find-that-the-er-was-closed-their-story-is-one-of-many-1.6545043

- Kelen GD, Wolfe R, D’Onofrio G, Mills AM, Diercks D, Stern SA, et al. Emergency department crowding: the canary in the health care system. NEJM Catalyst Innovations in Care Delivery. 2021;2(5).

- Nundy S, Cooper LA, Mate KS. The Quintuple Aim for Health Care Improvement: A New Imperative to Advance Health Equity. JAMA. 2022 Feb 8;327(6):521–2.

- Abu-Laban RB, Christenson J, Lindstrom RR, Lang E. Emergency care clinical networks. CJEM. 2022;24(6):574–7.

- Position Statements [Internet]. CAEP. [cited 2023 Sep 6]. Available from: https://caep.ca/advocacy/position-statements/

- Breaking News [Internet]. CAEP. [cited 2023 Sep 20]. Available from: https://caep.ca/breaking-news/

- Varner C. Emergency departments are in crisis now and for the foreseeable future. 2023 Jun 19;195(24):E851–2.

- Gonzalo JD, Chang A, Dekhtyar M, Starr SR, Holmboe E, Wolpaw DR. Health Systems Science in Medical Education: Unifying the Components to Catalyze Transformation. Acad Med. 2020 Sep;95(9):1362–72.

Chapter 13: Emergency Medicine in the Era of Climate Change

|

The overarching purpose of this report is to catalyse system redesign to allow for better emergency care in the future. Climate change is the biggest global health threat of the 21st century, [2] and tackling it is our biggest health opportunity. [3] We exist within a global ecosystem in which the health of our patients and our future ability to treat it are inextricably intertwined with the world around us. [1]

Though emergency medicine has traditionally given little thought to our environment beyond illness resulting from extreme heat or cold, our very ability to do our job with the needed resources is now threatened by the potential for supply chain dysfunction, infrastructure challenges, and social disorder attributable to climate change. These challenges coexist with increased patient presentations for physical and mental health compromise related to wildfires, floods, emerging infectious diseases and much more. [4]

This situation is being met by an emergency medicine workforce that is significantly under-educated on climate-related health issues. Curricular surveys show most medical students are still not being taught about climate change or air pollution, [5] and while research has found that most physicians believe climate change is a health threat, they do not feel prepared to manage the situation. [6] Only a minority of those surveyed by our EM:POWER Task Force feel climate change is a very important (11%) or important (22%) issue facing the Canadian healthcare system overall [EM-POWER survey]. This rate of change in our thinking isn’t keeping up with what’s happening on our planet and is unlikely to achieve a viable outcome because just as time is brain, time is planet.

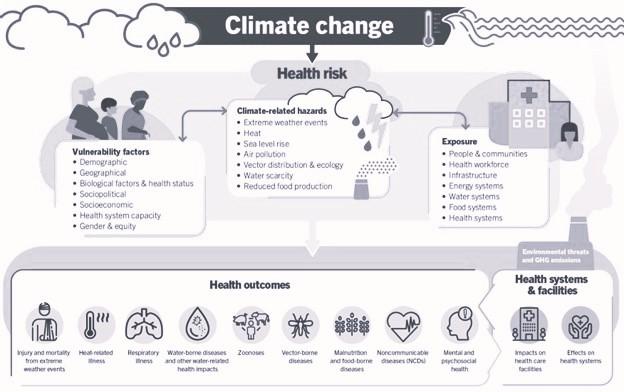

Figure 20. An overview of climate-sensitive health risks, their exposure pathways and vulnerability factors. Climate change impacts health both directly and indirectly, and is strongly mediated by environmental, social and public health determinants. (World Health Organization Report, October 2023)

Emergency medicine must use the breadth and depth of its collective knowledge and skill—in science, education, disease management, bioethics, and advocacy—to address the challenges of this new era of altered planetary physiology: the Anthropocene. [7]

| Physical Health | Zoonoses (infectious diseases spreads from animals to humans)

Heat/Cold Injury Respiratory/Cardiovascular illness Hurricane/Floods/Drowning |

| Mental Health | Geographic displacement and associated mental distress, mood disorders, suicidality.

Weakened social cohesion, violence, aggression |

| Costs* | Increased ED visits

Increased hospital admissions Displaced populations |

| Equity | The greatest impact of climate change is on marginalized populations, such as:

Poor/homeless Visible minorities Workers in hazardous conditions (e.g., construction) Those living in environmentally-fragile areas. Those with pre-existing health conditions Older persons Children Those with disabilities |

| Access | Hospital evacuation

Crowding with decreased access |

| Workforce | Overwork and burnout, leading to attrition.

Increased absenteeism Leaving areas inordinately impacted by climate change |

| Quality | Crowding and boarding with negative care experience

Negative impact on healthcare team well-being Exacerbated health inequity Increased costs Negative impact on population health Supply chain disruption |

Table 6. Impact of climate change on health and health systems [8]

*Findings replicated by the Canadian Climate Institute [9]

Priority Areas for Action and Recommendations

There are four priorities for emergency medicine as we reframe health and healthcare on a planet whose ecological foundations have become unstable:

- Adapt to emerging conditions, now and in the near future.

- Mitigate the trajectory of change.

- Educate ourselves, our patients, and our elected leaders.

- Do our part to make planetary health a societal priority.

Adaptation

Climate emergencies are already increasing in frequency and severity. There must be an understanding within emergency programs of local climate risks, along with adaptation of design and operational plans:

- Emergency physician leaders should be familiar with patient population-health, and ED operational impacts of current climate change events, such as wildfires, prolonged heat events, floods, and population displacement.

- Canada has a National Adaptation Strategy for climate change, [10] which hosts a Disaster Risk Reduction table. Much of this is relevant to emergency physicians and should be integrated into EM training (see Education below). Emergency medicine disaster experts should be integral parts of this conversation and sit at the table.

Mitigation

While measures to combat climate change are the foundation of our response to this crisis, it remains true that, whatever our response, some of the impacts of climate change will remain with us for years to come. Because of this, mitigation of potential immediate-term risks is critical:

- ED directors must be aware of the temperature and precipitation projections for their region, plan for the consequent operational impacts, and work with climate-savvy architects and engineers to design infrastructure for a changing environment, and

- Emergency medicine leaders must collaborate with governments and other healthcare stakeholders to ensure the necessary supply of pharmaceuticals and other products and mitigate their impact on the environment.

Education

Teaching of climate-related emergencies within a broader understanding of the Anthropocene should be part of residency training and continuing professional development. There is evidence that the general population underestimates the immediate risks of climate change on health—such as mental health, infectious diseases, and heat-related illnesses. [11] Physicians therefore have roles as both learners and public educators in climate change:

- Because emergency physicians are familiar with treating patients impacted by extreme heat, wildfires, and floods, they should increase their role in public education related to climate change and climate emergencies, and

- CAEP should harness its internal expertise in education, research, and public affairs—along with allies from other disciplines—to help illustrate and mitigate the health impacts of climate change.

Prioritization: Make Health and Wellbeing an Overarching Goal

It will be impossible to create a highly functional health ecosystem in any individual country within a destabilized global ecosystem. Currently, no country meets its population’s basic needs while keeping resource use at a sustainable level. [12] And modelling suggests that it will be difficult to continue to increase growth in GDP while decreasing its impact on the planet. [13] This puts us at risk of crossing global tipping points that could lead to runaway warming and vast destabilization, the so-called hothouse earth. [14] An urgent dialogue is necessary to reframe our social priorities, and as stewards of the health system, physicians must necessarily become stewards of the planet as well.

Conclusion

The foundations of human health and health systems are being destabilized by climate change. All health professions require a reframing of their priorities and redesign of their systems to include an evidence-based, values-driven response to the ecological emergency facing us. This includes expanded education and professional development, engagement in national and provincial adaptation strategies, and leadership in the public domain. It’s a daunting challenge, but if there’s any specialty with the skill and character to adapt to rapidly-changing conditions, it’s emergency medicine. A broad understanding of the urgency and complexity of the emergency before us is lacking, but there is no shortage of information—and no time to waste.

Additional Reading

- The theme of direct health impacts caused by future weather and climate is frequently noted in the Canada’s Changing Climate series subject area reports, which are essential reading for physicians.

- The Climate Atlas of Canada has a very accessible library of short articles, and the health section has some directly relevant topics.

- From the World Health Organization, the direct impact of climate change on health.

References

- Chochinov A, Petrie DA, Kollek D, Innes G. EM:POWER: if not us, who? If not now, when? CJEM. 2023 Jan;25(1):11–3.

- WHO issues urgent call for global climate action to create resilient and sustainable health systems [Internet]. [cited 2023 Jun 29]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news/item/24-05-2023-wha76-strategic-roundtable-on-health-and-climate

- Watts N, Adger WN, Agnolucci P, Blackstock J, Byass P, Cai W, et al. Health and climate change: policy responses to protect public health. Lancet Lond Engl. 2015 Nov 7;386(10006):1861–914.