Current Position: Consultant for Alberta Health Services, Calgary AB

Current Position: Consultant for Alberta Health Services, Calgary AB

Background:

Dr. Cheri Nijssen-Jordan is a highly accomplished medical professional with a career spanning over 40 years. She began her medical journey in Saskatchewan, where she completed her medical school education. From there, she migrated to different locations, including Halifax, Ottawa, and Calgary, where she established a strong base due to the city’s convenient international airport and proximity to the mountains.

Dr. Nijssen-Jordan’s expertise lies in pediatrics, specifically pediatric emergency medicine. She started her career as a staff member in pediatric emergency in Halifax, where she played an active role in various medical associations and committees, such as the Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians (CAEP) and the Royal College emergency medicine specialty committee. She even contributed to defining the pediatric emergency sub-specialty and the pediatric component of the emergency medicine sub-specialty.

In addition to her pediatric specialization, Dr. Nijssen-Jordan’s first exposure to international work involved her time as one of the only doctors in a hospital in Lesotho, Southern Africa. This early exposure to global health motivated her to pursue international work and volunteer with organizations like Doctors Without Borders.

Throughout her career, Dr. Nijssen-Jordan has held several leadership positions within Alberta’s medical system. She served as the Director and Division Head of Pediatric Emergency Medicine at the Alberta Children’s Hospital and later became the Facility Medical Director of the South Health Campus hospital. She has also been involved in teaching pediatrics at the University of Calgary’s Faculty of Medicine.

Dr. Nijssen-Jordan’s dedication to public health was evident during the COVID-19 pandemic when she co-led the COVID Vaccine Task Force at Alberta Health Services, overseeing the distribution of COVID-19 vaccines throughout the province.

Outside of her clinical and administrative work, Dr. Nijssen-Jordan has actively contributed to various medical boards and organizations, including the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Alberta, the Canadian Medical Alert Foundation, and the City of Calgary Medical Control Board for Emergency Medical Services.

She holds a Doctor of Medicine degree from the University of Saskatchewan and a Master of Business Administration from the University of Calgary, highlighting her commitment to both medical expertise and healthcare management.

Why is Global EM important to you?

“I would have to say that the key thing for me is that universal healthcare and emergency care has always been something that I consider a right of every person and it doesn’t matter where you’re from or who you are […] a human is a human”.

Dr. Cheri Nijssen-Jordan’s commitment to universal healthcare and emergency care is a central aspect of her career. She strongly believes that everyone, regardless of their background, deserves access to healthcare. For her, being human is the only affiliation that matters, transcending differences in color or origin.

Early on in her career, Dr. Nijssen-Jordan recognized the privilege of living in Canada and North America with abundant healthcare resources. However, she felt the need to venture somewhere that lacked the same level of medical infrastructure. Her goal was to develop robust clinical skills and provide essential care to underserved populations. This desire led her to pursue medicine, driven by the genuine intention to help others.

Dr. Nijssen-Jordan embraced the opportunity to enhance her clinical expertise, serve communities in need, explore different cultures, and foster connections with people worldwide. With the support of her husband, who possessed engineering skills in rural development and water sanitation, they formed a formidable partnership.

How does your involvement in Global EM impact your practice? How does it fit into your career goals?

“If you have a mom that’s concerned about a fever in her kid in Canada, that’s no less concerning to her than a fever of a kid to a mom in South Africa”

Dr. Cheri Nijssen-Jordan believes that her experience working in areas with limited medical resources has significantly enhanced her clinical skills and resource utilization. She emphasizes that her history taking, physical examination, and overall clinical abilities have greatly benefited from her international work. This exposure has made her appreciate the excellent healthcare opportunities available in Canada.

Dr. Nijssen-Jordan’s international experience has made her a more patient consumer, as she understands the challenges faced by underserved populations who may have to travel long distances or endure extended wait times for care. She urges her colleagues and the public to recognize the privileges they enjoy and the high quality of care available in Canada.

Balancing between different types of clinical practice has been a challenge, but Dr. Nijssen-Jordan has developed the ability to compartmentalize and adapt to different protocols and resource availability. She has learned that regardless of location, the concerns and needs of patients and their families remain the same. This understanding keeps her grounded and focused on providing the best care possible, regardless of the circumstances.

Have you done any focused training related to Global EM?

Dr. Cheri Nijssen-Jordan’s commitment to global health and her desire to enhance her clinical skills led her to pursue additional training in Tropical Medicine and hygiene. Recognizing the importance of understanding diseases rarely seen in Canada, she obtained a diploma in Tropical Medicine in Lima, Peru. Additionally, she recognized the value of ultrasound as a versatile tool, particularly in remote areas with limited resources. To better utilize this technology, she underwent extra training in bedside ultrasound, which proved invaluable in her practice, especially in rural and underserved regions.

She pursued a Master of Business Administration (MBA) degree. This decision proved instrumental in developing her operational management skills, enabling her to effectively manage departments, negotiate, handle HR issues, and approach conflicts with patients. She advocates for including similar courses in emergency medicine training, as they provide fresh perspectives and valuable insights, especially for those involved in global health initiatives where intergovernmental relations and negotiations with diverse entities are critical.

What current projects are you involved in or past projects that you would like to share?

Dr. Cheri Nijssen-Jordan has been involved in various noteworthy projects throughout her career. In North America, she played a pivotal role in designing Calgary’s new Children’s Hospital and the South Health Campus. Additionally, she served as an administrator in Fort McMurray, gaining valuable experience in running a portion of the healthcare system.

However, one of her most fulfilling projects took place in Laos, Southeast Asia, where she had the opportunity to open and run a new Children’s Hospital. Dr. Nijssen-Jordan organized a team of over 126 volunteers, including physicians specializing in emergency medicine, pediatrics, and residents from both disciplines. The project focused on improving emergency care, and the hospital’s emergency department became a training ground for resuscitation skills and critical care.

In Laos, there was a significant number of small infants with population-specific vitamin deficiencies, leading to cardiac arrest and failure. The team implemented a protocol involving resuscitation, intubation, and administering thiamine. After approximately two hours of treatment, these infants would regain consciousness, breastfeed, and be discharged the following day with appropriate ongoing management. The experience provided ample opportunities for practicing intubation and teaching critical skills to residents and staff. The knowledge exchange and teaching opportunities left a positive impact on all involved, fostering ongoing support for the hospital in Laos.

Tell us about one memorable city or country where you’ve worked?

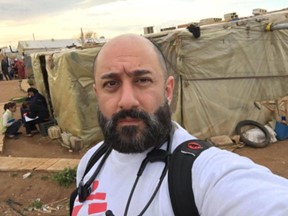

When asked about her most memorable city or country where she has worked, Dr. Cheri Nijssen-Jordan acknowledges the difficulty in choosing just one. However, her mission in northern Syria with Doctors Without Borders stands out as the most impactful experience for her.

As a flying pediatrician, Dr. Nijssen-Jordan was responsible for various projects, including pediatric care and covering adult emergency medicine. Working in a war zone provided a unique perspective, where she realized that regardless of which side a person was on, once injured, they became a casualty deserving of medical attention. Doctors Without Borders operates under the principle of treating anyone in need, irrespective of their affiliation.

The situation in Syria deeply saddened Dr. Nijssen-Jordan. The country had a strong healthcare system with renowned research and highly skilled medical professionals. However, the conflict in 2011 devastated the system, leaving a profound impact. She reflects on the challenge of rebuilding the healthcare infrastructure and providing care to combatants and civilians alike.

While each project has had its memorable moments, such as teaching emergency medicine courses in Kuwait and Taiwan or conducting a bedside ultrasound course in the Central African Republic, the experience in Syria had a profound impact on Dr. Nijssen-Jordan. Treating patients, regardless of their background, remains a core principle in her humanitarian work.

What are some unique challenges that you have faced while providing emergency medical care in different countries or regions?

“It’s trying to use the resources that you have in the best possible way to give the best outcome for the patient. For me that’s one of the the most unique things about every single place because they’re all different”

In North America, access to various specialty consultations is readily available, ensuring optimal patient care. However, this is not the case in many global health settings. Physicians must rely on critical thinking to diagnose and treat patients with limited resources. Dr. Nijssen-Jordan shares an example from Pakistan where resuscitation efforts for babies born at home were challenging due to delayed arrival, resulting in long periods of hypoxia and subsequent complications.

She emphasizes the importance of using available resources effectively to achieve the best patient outcomes. Dr. Nijssen-Jordan highlights the varying healthcare landscapes in different regions. For instance, she mentions the impact of war in Syria, where a well-established system for treating thalassemia collapsed, leading to unsafe practices. Efforts were made to reinstate safe transfusions and secure affordable medications.

Dr. Nijssen-Jordan also stresses the need for adaptability and critical thinking in global health emergencies. She shares her experience in the Central African Republic, managing a measles epidemic alongside the ongoing COVID-19 outbreak. She encourages healthcare professionals to explore different avenues to contribute to global health, such as fellowships, partnerships with organizations like Doctors Without Borders and the Red Cross, and providing immediate assistance during crises. She advises against engaging in medical tourism and emphasizes the importance of sustainable contributions that have a lasting impact on healthcare outcomes worldwide.

James Stempien

James Stempien Arjun Sithamparapillai

Arjun Sithamparapillai Segun Oyedokun

Segun Oyedokun Alicia Ruhi Cundall

Alicia Ruhi Cundall Current Position:

Current Position:  Current faculty/position?:

Current faculty/position?:  Current faculty/position?:

Current faculty/position?:  Current faculty/position?

Current faculty/position? Why is Global EM important to you?

Why is Global EM important to you? Current faculty/position?:

Current faculty/position?:  Name:

Name: Current faculty/position?:

Current faculty/position?: Current faculty/position?:

Current faculty/position?: Current faculty/position?:

Current faculty/position?: