Shift Work and Sleep: Your Life Depends on It

By Sara Gray (aka someone who has definitely fallen asleep in an elevator)

Picture this: It’s your third evening shift in a row. You’ve been sleeping like a caffeinated toddler thanks to a family crisis, and a patient with six months of occasional toe pain is now yelling at you for asking about their family doctor. They accuse you of being “insensitive,” and suddenly you’re wondering if you’re the problem—or if it’s the fact that your circadian rhythm is currently being slow-roasted like a rotisserie chicken. Two days later the patient files a complaint, and now you’re half-convinced the universe wants you to take an office job somewhere involving ferns and Muzak.

Before you start Googling “non-clinical careers where nobody yells at me,” let’s talk about what’s actually happening: shift work, fatigue, and the very real ways they warp your brain, your health, and your reactions to frustrated humans with no GP.

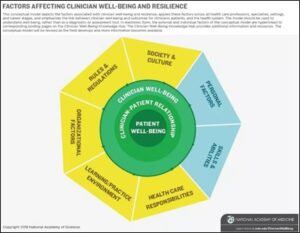

Shift work doesn’t just make you tired; it reshapes your long-term morbidity and mortality—and not in a pretty way. Circadian misalignment (a fancy term for “your internal clock is screaming”) is associated with:

- Metabolic syndrome—including diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia and abdominal obesity

- Increased rates of cardiovascular disease

- Menstrual irregularities and dysmenorrhea

- Depression, anxiety, burnout

- Cancer (Yes. Cancer. Boivin et al., 2021)

Add in the classic EM tradition of driving home half-unconscious after a night shift, and the risk of motor vehicle collisions goes up, too. And it’s not just your health. Night shifts are associated with a higher risk of workplace accidents—which is unsurprising when your brain is functioning at the level of a warm bowl of oatmeal.

We all know we’re slower and grumpier at 4 a.m., but the cognitive toll is deeper:

- Reduced alertness and overall activity at night

- Slower reaction times and lapses in attention

- Reduced concentration and impaired data processing

- Worsening performance across consecutive night shifts—especially memory and attention (Boivin et al., 2021; Mitra et al., 2008; Leso et al., 2021)

So would you have de-escalated that angry toe-pain patient more effectively if you were rested? Probably. Fatigue constricts emotional bandwidth, narrows cognitive flexibility, and shortens your fuse… which is a tough combo when someone is yelling at you because their x-ray from last month was normal.

But what about those colleagues who seem to thrive on night shifts? Not all shift workers are built the same. The way shift work affects you depends on:

- Internal factors: your chronotype (“morning lark” vs “night owl”), genetic traits, vulnerability to sleep loss

- External factors: family roles, social obligations, commuting

- Workplace factors: staffing, workload, policies, hazards (Gurubhagavatula et al., 2021)

Some emerg docs glide through nights effortlessly, like vampires kicking ass. Others drag themselves through the dark like Victorian chimney sweeps. And some can only tolerate nights when the stars align, the in-laws take the kids, and the dog doesn’t throw up on the carpet.

Understanding this interplay is key to scheduling that doesn’t destroy people. We need to create shift scheduling that allows for this individual variability, and create the flexibility normal busy humans need. What strategies are valuable for healthier shift scheduling?

- Match shifts to chronotype and lifestyle

Night owls → more evening shifts

Morning larks → more morning shifts

Nobody → back-to-back nights on short recovery

Aligning shifts with chronobiology increases sleep duration—and makes people hate their jobs less.

- Use forward-rotating schedules

Day → evening → night

NOT the reverse.

Backward rotation is like telling your circadian system to somersault while on fire.

- Build in adequate recovery time

Less than 11 hours between shifts = insomnia, excessive sleepiness, cranky humans.

More consecutive shifts = longer recovery needed.

(Boivin et al., 2021; Gurubhagavatula et al., 2021)

- Shorter shifts are more efficient

Shifts >12 hours = higher risk of mental fatigue and errors.

Shorter shifts (7–8 hours) = better productivity.

Casino shifts (10 p.m.–4 a.m. or 4–10 a.m.) show promise in protecting “anchor sleep”—your precious nighttime sleep block.

- Tailor the schedule to department realities

No two EDs are the same. Useful factors to consider:

- Patient arrivals and acuity

- Physician productivity

- Breaks (yes, breaks, we should have them)

- Day-of-week variability

- Rural docs juggling office work

- Preferences and personal circumstances

Hiring nocturnists, incentivizing less-loved shifts, and compensating for wrap-up time can all reduce burnout.

And above all, we need transparency, fairness and consistency. Clear rules for holidays, weekends, sabbaticals, and shift distribution prevent simmering resentment—the kind that boils over in group chats at 2 a.m.

Why Sleep Really Matters

We’re not whining about inconvenience; we’re talking about safety, health and career longevity. Poor scheduling and chronic sleep disruption don’t just make shifts unpleasant—they shorten careers, increase medical errors, and harm clinicians’ physical and mental health.

Emergency medicine needs leaders willing to embrace data-driven scheduling that respects human physiology. Not rigid, one-size-fits-all templates. Not martyr culture. Not “we’ve always done it this way.”

We need schedules that keep us healthy enough to keep doing the job. Because your sleep isn’t a luxury. It’s not optional. And in emergency medicine, your life—and your patients’ lives—genuinely depend on it.

References:

- Boivin DB, Boudreau P, Kosmadopoulos A. Disturbance of the Circadian System in Shift Work and Its Health Impact. Journal of Biological Rhythms [Internet]. 2021 Dec 30;37(1):3–28. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8832572/

- Mitra B, Cameron PA, Mele G, et al. Rest during shift work in the emergency department. Aust Health Rev 2008;32:246–51.

- Leso V, Fontana L, Caturano A, Vetrani I, Fedele M, Iavicoli I. Impact of Shift Work and Long Working Hours on Worker Cognitive Functions: Current Evidence and Future Research Needs. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021 Jun 17;18(12):6540.

- Gurubhagavatula I, Barger LK, Barnes CM, Basner M, Boivin DB, Dawson D, et al. Guiding principles for determining work shift duration and addressing the effects of work shift duration on performance, safety, and health: guidance from the American Academy of Sleep Medicine and the Sleep Research Society. Sleep. 2021 Jul 15;44(11).

- Zaerpour F, Bijvank M, Ouyang H, Sun Z. Scheduling of Physicians with Time‐Varying Productivity Levels in Emergency Departments. Production and Operations Management. 2021 Nov 6;31(2):645–67.

- Dong AX, Columbus M, Arntfield R, Thompson D, Peddle M. P048: Profiling the burdens of working nights. Traditional 8-hour nights vs staggered 6-hour casino shifts in an academic emergency department. CJEM. 2017 May;19(S1):S94.

- Croskerry P. Canada: Abstract 035 Casino shift-scheduling in the emergency department: a strategy for abolishing the night-shift? [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jul 17]. Available from: https://emj.bmj.com/content/suppl/2002/08/28/19.4.DC2/abs34to75.pdf

- Zwemer Jr FL, Schneider S. The demands of 24/7 coverage: using faculty perceptions to measure fairness of the schedule. Academic emergency medicine. 2004 Jan;11(1):111-4.