The authors would like to thank the many individuals, organizations and CAEP committees that made formal submissions to the Task Force; unfortunately, we were unable to include all of them. The following appendices are included because they address specific subpopulations at risk or were deemed to be of practical value to healthcare leaders as they consider system redesign.

APPENDICES

Appendix 1: Submission from CAEP’s Rural Remote and Small Urban Section

This untenable situation prompted The Society of Rural Physicians of Canada to shed light on the health care obstacles these communities struggle with. The Rural Road Map: Report Card on Access to Health Care in Rural Canada provides an excellent and comprehensive call to action on many of these challenges, with suggested approaches to improving care and equitable access.

There is, of course, extensive overlap with the issues facing all emergency care in Canada. Taken as a whole, there is no coherent healthcare system. At the highest level, the federal/provincial separation (federal money but provincial rules, federal oversight but inter- provincial disparities) is a problem that at the very least needs interprovincial universal agreement in principle. More to the point, legislation is needed to allow for many of the changes long called for by the various organizations consulted for this project.

National licensures/certifications for all medical and paramedical professions seems one of the most obvious first goals. At the provincial level, disparate health regions/zones/corporations have resulted in deeply ingrained challenges. Such divisions create innumerable obstacles to providing effective and timely transfers, and referrals – or even basic healthcare access for various populations.

At the system level, the problems multiply. Fee-for-service can be considered perverse remuneration, trading volume for quality. That statement is not to be taken lightly, as it is not to discredit the countless dedicated and talented providers who always have, and continue to offer, the best possible care to their patients. Yet it reveals a system that unintentionally undervalues preventive care and education, and thrives on people being sick, needing procedures and prescriptions, etc. The downstream effects are the situations we all face, that of overfull understaffed facilities, excessive wait times and sub-par care.

Emergency care challenges inevitably vary by geography and facility. As a profession, there’s a wide range of obstacles. The high-level matters include certification requirements by the credential-granting organizations (e.g. CCFP/CAC-EM/FRCP/NP/PA); human health resource planning, defining scope of practice; and accessible and available training and resources. Other issues to consider are the front-line challenges, simply the lack of staff, and the urban-centric nature of specialized tertiary care, a logistical fact that will unlikely change. This highlights the difficulties of patient transfers and most-appropriate dispositions or treatment outcomes for patients based on location and access.

Emergency department (ED) boarding, where patients are kept in the department for an extended time because of the lack of hospital beds, is not an ED problem, but an accountability problem that lies up the chain. Advocating for high-level change is the thrust of this project and the call from all the emergency organizations involved.

The lack of technology-driven solutions to some of these issues is particularly disappointing in a country the size of Canada. Strategically placed CT scanners that can be run by the many well- trained techs with dedicated virtual radiology support from tertiary centres could have a massive impact on cost and time reductions in patient care and disposition, to say nothing of best practice.

“Surge” has a somewhat flexible definition that requires context. The difference between a mass casualty incident and a disaster are available resources that overlap with the ability for them to be mobilized and leveraged. There’s also a difference between predictable and unpredictable, such as flu-season vs. new global pandemic.

If the question is how to be prepared for the unexpected, the answer should be implicit in the understanding of emergency medicine. There are two simple—if not exactly easy—requirements:

- Broad training and preparation in emergency preparedness: planned high-fidelity simulation, interprofessional and inter-departmental at a minimum. (Anyone involved in Disaster Management planning will attest to the lack of support for that.)

- Timely resource availability: Emergency Departments and programs cannot be allowed to be run like restaurants, with just-in-time delivery of supplies, and needing every seat filled to make ends meet.

Emergency Departments MUST be protected from running at 100% capacity. That is the current default, and it GUARANTEES system failure as it dismisses the very reason such departments are needed; the unplanned, the unexpected and the surge. These are the situations that require an ED with empty beds and a full complement of available staff (nurses, respiratory therapists etc. not committed to the care of patients already in house).

To the accounting firm, to the administrator, to the hospital board, that looks like wasted money, unused resources. They do not live in our world and do not appreciate the reality. There must be legally enshrined protection of resources to allow for immediate response to surges. Experience has shown that any appearance of “surplus” will inevitably evaporate rapidly once a crisis is declared over.

Let us remember Rudolf Virchow, the father of pathology, and the aphorism he coined nearly two centuries ago: “Medicine is a social science and politics is nothing else but medicine on a large scale. Medicine as a social science, as the science of human beings, has the obligation to point out problems and to attempt their theoretical solution; the politician, the practical anthropologist, must find the means for their actual solution.”

The changes needed are not at the level of emergency departments or practitioners. They are far broader in scope and mandate. How a community is able to respond to a surge only exemplifies this.

References

- Rural Road Map Implementation Committee. Call to Action: An Approach to Patient Transfers for Those Living in Rural and Remote Communities in Canada. Mississauga, ON: College of Family Physicians of Canada and the Society of Rural Physicians of Canada; 2021

Appendix 2: Submission from Health Equity Committee

How would you encapsulate the major problems you perceive in the current status of the health care system as a whole:

The health care system is under tremendous strain from our society’s large burden of illness related to the social determinants of health. This is particularly true in the emergency department (ED), which acts as a shock absorber. When patients cannot access primary care, they end up in the ED for prescription refills, low acuity issues, and exacerbations of chronic illnesses that have gone unattended. When inpatient wards have a high burden of Alternate Level of Care (ALC) patients – and available acute beds are limited – overcrowding results, and admitted patients are boarded in the ED for extended periods of time.

The ED has seen a recent rise in the number and proportion of visits related to social illnesses. Patients experiencing homelessness, for instance, often present to the ED simply because they cannot access stable, or even temporary, housing. They may also present with medical complications resulting from this social illness, such as frostbite or even hypothermic cardiac arrests in winter months.

These examples demonstrate how the burden of social policy failures shift to the ED from under-resourced community supports, such as affordable housing programs or shelters, and also how this shift results in worsening outcomes for our patients, and higher costs to the system overall.

To be clear, reducing ED use is not the primary concern; these visits represent a failure of upstream social and health policy and an inefficient use of public resources that fuel the impetus for ED providers to drive social change. As emergency room providers, we bear intimate witness to these failures, and advocating for upstream solutions is therefore an important role we must fulfill.

Emergency departments are well equipped to collect data on these social and health policy failures. For example, EDs could publicly report on the following metrics:

- Proportion/number of visits to the ED for patients without primary care access.

- Proportion/number of visits to the ED for patients who could not access primary care in a timely way (for example same day or next day).

- Proportion/number of visits to the ED related to a lack of pharmaceutical coverage.

- Proportion/number of visits to the ED related to a lack of dental care coverage.

- Proportion/number of visits to the ED related to a lack of physiotherapy coverage.

- Proportion/number of visits to the ED related to a lack of mental health care coverage.

- Proportion/number of visits to the ED due to substance use disorders.

- Proportion/number of visits to the ED related to housing instability/ homelessness.

- Proportion/number of visits to the ED related to income insecurity.

- Proportion/number of visits to the ED by race or ethnicity.

- Proportion/number of visits to the ED due to lack of appropriate home care services.

- Proportion/number of visits to the ED due to a lack of appropriate long-term care.

- Proportion/number of visits to the ED due to precarious/unsafe labour.

While these data require effort to collect, this information would provide a critical window into the shocks due to social and health policy failures that are currently being absorbed by our EDs. It could be used to put pressure on governments to address upstream issues and relieve pressures on the ED.

This data could be collected through intermittent surveys of random patient samples on the factors driving the reason for the specific ED visit that day. Collecting and reporting these metrics would ideally be mandatory, and part of a coherent strategy by all levels of government to guide efficient and effective public policy (though there may be some reluctance to have such a bright light shone on these failures). However, independently collecting these metrics and publicly reporting them would empower ED providers and citizens to advocate for better public policies.

What are the obstacles to delivery of emergency care (as you define it)?

Social safety Net Easily Overwhelmed: Many of the operational systems that deal with upstream determinants of health continually function in a state of crisis. There seems to be little capacity, and in this environment, it is often quite challenging to address the social determinant itself or to provide meaningful solutions to delivery of care.

For instance, in most settings, people experiencing homelessness find it a challenge to access emergency shelter spaces. Housing options or a way out of homelessness that meet the needs of people impacted are quite limited. People who use drugs or experience mental health emergencies face similar challenges.

In times of crises, service operators become easily overwhelmed and difficult to mobilize. In a recent example, Shigella outbreaks occurred in two major cities (Edmonton and Vancouver) among people experiencing homelessness. This led to significant surges in ED visits and ultimately admissions to hospital. With resources so quickly overwhelmed, it took weeks to mobilize a community-based response (hygiene stations and more bathroom access) that helped to break the transmission of illness and treat people more reliably outside hospitals.

Undoubtedly, climate emergencies that displace resources will more drastically affect people who are unable to access basic needs. We have already seen seasonal increases in deaths and injuries for people facing injuries from environmental exposures in both winter and summer climate extremes. These are expected to rise in the future.

Institutional Distrust: Many groups, including racialized individuals (especially those from Indigenous and Black communities), and people who face social precarity (such as those who use drugs) face challenges just seeking care. This adds complexity to providing emergency care, subsequent treatment plans, and follow-up resources.

Rigid and hierarchical processes make it difficult for us to adapt to the needs of an individual. Rapid mobilization of communities is essential in times of mass casualty or environmental catastrophes; building trustful relationships are useful guiding principles that allow for emergency care to be flexible and in the best interests of the people receiving it.

System Planning: Many places and communities with high needs do not have readily available access to ED care. We need to systematically consider and define what emergency care looks like and have resources and strategies to deliver medical treatment for communities that need them. At times of system level surges, pre-built capacity is essential to deliver emergency care. A support system of primary care, pharmacists, overdose prevention workers, and other allied- health professionals with expandable skill sets are useful parameters to consider in system- wide planning; this will allow for meaningful regionalization of resources.

What actions do you think might provide solutions, who are the stakeholders who need to take those actions and what time frame should they be taken in (Immediate, within two years, within five years)?

- Action

NEED TO INVEST UPSTREAM

Accountable Stakeholder

Federal and provincial governments

Timeline

Intermediate and long-term

We as a society understand that when everybody has the basics, we all have more and we are all healthier. The equitable system costs all of us less and builds a healthier society.

Many of the resources we spend are on costly impacts of a fragmented and out-of- reach system that does not address people’s basic needs. Access to housing, dental care, medications, and primary care are core elements of investments in the upstream.

Alongside, there is an urgent need to prevent ongoing financialization of the housing market. This continues to be one of the biggest drivers of economic insecurity and lack of affordable housing across the country. The downstream effects include rising homelessness and challenges for people who are homeless to find rents that are affordable within the social welfare system.

- Action

DATA CAPTURE

Accountable Stakeholder

Hospital Administration

Timeline

Immediate

EDs are the ultimate downstream manifestation of health outcomes that are impacted by poor upstream factors. Our EDs capture a wealth of data that tells us what’s wrong with the rest of the health system and society at large. While we routinely discuss these factors, we unfortunately have a very obscure understanding of the populations we serve. We need to regularly capture health indicators such as housing status, and income-based medication coverage alongside factors, such as race and gender, that impact health.

There should be mandatory reporting around the metrics measured in the databases. These datasets should also help guide accreditation standards and setting agendas and priorities e.g. setting priorities such as benchmarking that under 10% of ED visits should relate to impacts of homelessness.

- Action

INCREASING COMMUNITY CAPACITY

Accountable Stakeholder

Health profession regulatory colleges

Timeline

Intermediate

We need to get better at defining skills before a surge takes place by building opportunities and increasing mobility between regions for health care staff. This may mean providing virtual or on-site support more seamlessly to areas affected by a crisis or natural disaster in direct emergency provision or also in other scenarios, such as opioid agonist therapy (treatment for those with an opioid disorder) and other basic service delivery. The regulatory frameworks make this challenging and difficult to mobilize, however pre- developed pathways would reduce the administrative burdens around these concerns in a longer-term emergency.

- Action

EMERGENCY CARE OUTSIDE THE ED

Accountable Stakeholder

Provincial governments

Timeline

Immediate

Many emergency care spaces don’t require ED care. We need alternate options for people.

Case example: Drug poisoning events take place in 6-7% of people who use drugs. Less than 1% of those require acute care resources or transport to a hospital.

Unfortunately, due to a lack of supervised consumption sites and only thinking of emergency care in EDs – most drug poisonings are transported to local EDs and require vast EMS and acute care resources.

Integrated emergency care options, for instance for drug poisonings, to be cared for in supervised consumption sites that have the expertise and capacity to care for drug poisonings. Patients can be observed and transferred when appropriate.

One of the barriers to moving care into the community and out of the EDs is often the medico-legal risk (that the patient will sue the provider); but we also need to consider the risk of not moving that care, of having overwhelmed ED systems where those who need acute care may not be able to get it in a timely and accessible way.

Are there any specific changes that must occur for the system as a whole to adapt to surges in demand (both short term such as a mass casualty and long term such as a pandemic)?

How We Need to Adapt for Surges: The system must be redesigned to ensure sufficient capacity in the community to support the majority of a response. This includes planning for the following: immediate access to shelter, income supports, food/water/medications/medical supplies, expanded access to primary care, additional mental health and substance use supports, and a rapid public health response to mitigate any delayed effects (from overcrowding, missed preventive health interventions).

ED and acute care resources should be reserved for those with critical illness or injury who can only be managed in an ED or acute care setting to ensure those with the highest acuity are seen in a timely and appropriate fashion. Local data should be used to inform planning and risk assessments. From a national perspective, cross-coverage of geographic locations should be facilitated by the regulatory colleges. This includes developing advance guidance around expanded scores of practice during an emergency situation; national licensure that can be granted immediately; advance planning with transportation partners to rapidly move healthcare workers to areas of need.

In essence, the ‘safety net’ needs to be in the community’s formal capacity to respond, not in the acute care setting.

Are there any specific changes that must occur for the system to deliver emergency care (as you define it) during surges in demand?

Prevention of illness and injury is paramount. This means ensuring maximal health of the population before, during and after major events. All individuals must have access to a primary care home, safe housing, a legal income that covers basic needs, access to medications and dental care, and a community support system. Capacity in the community must be in place to augment these supports during and after disaster situations.

Specific protocols must exist to increase staffing in emergency departments (from other areas of the hospital or via a national response system as outlined above), expanded space in the hospital and in the community via pop-up EDs (via pre-existing relationships and disaster planning); and increased access to pre-purchased supplies and equipment and/or other supply chain arrangements specific to disaster scenarios.

Appendix 3: Views from CAEP’s Pediatric Emergency Physicians

Data from arrivals to pediatric emergency departments (PEDs) demonstrate that most visits are after-hours, evenings, and weekends. This is partly because children seem sicker at bedtime, but also because many caregivers are unable to miss work to take their child to the doctor. Many visitors report coming to the ED with non-urgent complaints because they lack access to care, such as not having a physician, or are unable to see theirs in a timely fashion, or their doctor won’t see children in person if they’re infectious.

The government needs to look at where primary care can be bolstered, consider expanded licensing, increase the use of allied health where appropriate, and ensure families have a medical home they value and trust. Families need to be able to get care in a timely fashion by the provider that most matches their needs. This would decrease use of Emergency Departments (EDs), help with overcrowding, resource and staffing issues, and fragmented care, and reduce costs to the healthcare system.

Although virtual care can help to enable accessible care in many circumstances, it’s important to ensure the use is patient-centric, limited to beneficial situations and when a physical exam is not needed. For example, the most common complaints in pediatric emergency departments are fever and abdominal pain. Neither of these lend themselves to virtual visits and require physical exams to make a diagnosis.

From our lens it appears that current advice services like Telehealth in Ontario and 811 in Alberta for pediatrics lead many families to seek care in the ED. Many current protocols are too conservative. They do not leverage technology to source additional data to help drive decisions, and even when these services recommend seeing primary care, many come to the ED as noted above because they have challenges with access. Families need a reliable source to help them navigate the healthcare system and to know when they should worry.

We need primary care and a medical home to be accessible to all when there is demand. We also need to empower our population to increase health literacy, many families lack basic health literacy to understand when to worry, and how to manage common illness. We still see significant “fever phobia,” with many families seeking care for reassurance and guidance on how to manage common viral illnesses that don’t require a physician, prescription nor ED care—possibly not even primary care in many cases.

Current residency programs in family medicine dedicate only one month of training to pediatrics, and with the increased aging population, many trainees work in practices with little to no young patients, leading to a lack of comfort managing child health.

Caregivers who have a primary care physician often seek medical advice at PEDs to validate the care their child is receiving, and more often when their child is not improving. Recognizing we see a skewed and not representative population, many patients arrive at our department on antibiotics for viral illnesses, treatment that is not evidence-based, nor current. This reinforces families with the message to go to the ED for “good care,” leading many patients to bypass primary care, even when they have a provider. Investment is needed to ensure primary care physicians are comfortable seeing and treating children, and that mechanisms are put in place to ensure primary care physicians are quickly and easily up to date with common childhood presentations.

From a broader lens, our current healthcare system is designed, and providers rewarded, to treat illness. Funding is also not outcome-focused, and most providers are paid by volume.

Families feel rushed, and even when they receive the correct care, they often seek additional providers for reassurance or explanation, leading families to see two to three providers for the same problem to get the “right care.”

A focus on keeping our population healthy is lacking, along with insufficient funding to keep patients out of hospitals. There are many examples, such as IORA Health (a company in the US), that keep patients healthy so they avoid ED visits, need fewer interventions, and cost the system less. Also, a large portion of their care can be provided by allied health, non-physician professionals such as physiotherapists and dieticians, whose services are typically covered by a combination of public and private funding sources. Their involvement further decreases healthcare costs.

Most provinces lack a single unified patient record or an EHR (Electronic Health Record) that is easy to use. Patients receive care from many different providers across different locations, and it becomes challenging to deliver treatment with incomplete medical history. Lack of access to a full patient history or previous investigations leads to repeat testing and creates a risk of patient harm by making decisions with insufficient information.

We have seen a marked rise in the need for mental health, which was only further exacerbated by the pandemic. Unfortunately, resources have not kept pace, with many unable to get care until they are hospitalized. We fund psychiatrists, but not resources such as therapists who manage mental health. Many PEDs are not equipped with social work and mental health experts to appropriately support these patients when they do present. Current training is also lacking in this area. We need to look at expanding mental health resources in the community to increase access, prevent deterioration and/or need for the emergency department. And when patients do need the ED, ensure we have appropriately trained personnel.

Most importantly, the system is designed and funded to run at 100%. There is no room for growth, no room for surges that are anticipated, nor the ability to deal with those that are unexpected. This makes access to care difficult and creates stressful environments that lead to burnout among providers, further exacerbating the problem. We continue to push for ways we can do more with less within the same infective system; instead, we should be taking a bigger look at how we can recreate a patient-focused health system that keeps patients thriving, and at the same time has the capacity when they get sick.

Visits to pediatric emergency departments continue to rise year after year. For example, prior to the pandemic, the increase rate at SickKids Hospital in Toronto was 5% a year. Current PEDs lack sufficient physical space to provide care for these increased volumes. This is further exacerbated by a rise in boarders, due to a lack of inpatient beds that limit usable ED space. Current numbers of specialised ED nurses and physicians have not kept pace with the growth, and given the current pressures, many have decreased their full-time schedules or shifted to other work. In places with unions, ED nurses do not receive additional pay, despite the increased hazard and worse conditions compared to other departments, making it a less desirable area to work.

We need to ensure that we plan and train the appropriate number of personnel based on anticipated demand, and invest in retention strategies to keep the current skilled workforce in whom we have already invested. As noted in our healthcare system in general, most PEDs lack funding models that allow for allied health to expand and support the workforce by seeing low acuity patients. Funding is also not aligned to usage, nor adjusted for growth and complexity; even within a hospital, many services do not operate 24/7 to match ED needs, which creates further delays and pressures to the system.

Recommendations

Many surges, particularly in pediatric emergency departments are predictable. We see huge swings in volumes based on infectious patterns, with almost double the patients in winter months as in the summer. Current funding and physical space are based on averages, making it challenging to increase and decrease resources based on demand. This means we always run short during flu season. We also talk about surge as if it’s unexpected, yet we see the same patterns year over year. Hospitals need to be more fluid in their design to increase ED footprint as needed for both anticipated and unanticipated surges.

Staffing must look at having personnel cross-trained, increased ability to shift resources from areas that see a decline to those that need a rise. Changing licensing to cross Canada and making hospital privileges easier to obtain means resources can be moved to meet demand.

We need to leverage data, AI, and new technology such as wastewater monitoring to better predict and plan for anticipated and unanticipated spikes in patient volume.

The stress to the system is exacerbated when it is already running at 100% capacity. Investing in novel ways of providing care, along with prevention, would allow EDs and hospitals to operate closer to 80% so they can manage surges.

We need to shift how we view healthcare in Canada. There needs to be an investment in preventative care to keep people healthy, a strong primary care home where providers are sufficiently trained and comfortable with pediatric patients and can see them when they need to be seen—not Monday to Friday during business hours. Emergency departments should be focused on using their expertise to provide care to acutely unwell patients, traumas, etc., and not be the safety net for our healthcare system. Instead of intervening earlier with lower-cost solutions, this costly way of operating often results in patients deteriorating and getting to their worst.

General medical training for children’s emergencies is inadequate, leading to unnecessary, costly referrals to EDs, and suboptimal care. Residency education in Canada should be designed to ensure that acutely ill and injured children have access to high quality primary medical, virtually and in-person, as the case may dictate.

Appendix 4: Submission from CAEP’s Geriatric EM Committee

Emergency Departments (EDs) have long been considered the nexus of care with patients entering through self-referral, or referral by specialists or primary care providers. However, few who use them want to be there, and instead arrive as the result of a complex array of factors, including perceived illness severity or pain, difficulty in accessing primary care resources, and accessibility ease of ED-based resources.[1]

In recognition of these challenges, the CAEP Geriatric EM Committee recently developed a position statement to guide EDs across the country on making effective change aimed at enhancing the ED experience for older people, their caregivers and ED providers. This position statement can be summarized into eight core, evidence-based recommendations, supported by expert consensus and practical examples:

- Emergency departments recognize older people as key users and ensure departmental and institutional commitment to enhancing their care.

- Emergency departments establish local processes for interdisciplinary assessment of complex older patients, particularly those likely to be discharged, as this is associated with reduced ED length of stay, decreased return visits, decreased hospital admission, and improved functional outcome.

- Emergency departments involve family members and caregivers in the care of older people during their stay.[2]

- Emergency departments prioritize training and education of their staff to develop competence in emergency care of older people.

- Emergency departments develop standardized approaches to common geriatric presentations – including acute functional decline, frailty, delirium, polypharmacy, and adverse drug events, falls and dementia.

- Emergency departments modify the physical space with equipment to support the needs of older people, whether through basic low-cost modifications or through departmental redesign.

- To learn about their older patients, and to identify areas to enhance care, emergency departments should work to ensure high-quality transitions of care through reliable discharge communications between providers, patients, caregivers, and community supports.

- Emergency departments identify and collect data about key quality indicators about the care of older ED patients.

In relation to both in- and out-flow, the ED is intricately connected to its community and locally-based services. This link has long been recognized, but little enacted upon. With the demographic shift to a more aged population, EDs must work to ensure clear communication with community services, especially around challenges and opportunities. Providers need to build relationships with these services so that transitions of care to and from the ED are established, and pathways optimized. Creating this offers care options that may avoid unnecessary ED presentations altogether.

There are nationwide examples of innovative practice that can be grouped into the following programs of care:

- Enhance relationships with programs that promote appropriate ED avoidance:

- Prehospital access to responsive and timely home-based services including multidisciplinary care (Registered Nurse, Physician, Care Aid, Physical Therapist, Occupational Therapist, Pharmacy, Speech-Language Pathologist etc.). For example, the House Calls program in Toronto, Ontario: the Seniors First program in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan.

- Prehospital access to institutional-based care, including respite and rehabilitative services; short-stay units that allow enhanced care for a brief period while older people recover from challenges and functional decline associated with mild to moderate illnesses that otherwise do not require acute care.

- Use of alternatively trained health care providers such as Community Paramedicine and Nurse Practitioners to provide enhanced and timely community-based care that was previously unavailable due to either geographic constraints or other service limitations.

- Enhance programs and relationships with programs that promote improved ED through-put:

- Dedicated geriatric emergency management (GEM) nurses serve a critical role in the ED to help with care of older adults, and have been shown to reduce repeat ED visits.[3] They are trained to complete targeted assessments of older people in the ED, to help with clinical assessment and decision-making, and to make care recommendations and community referrals for additional services.

- Standardized communication tools from community providers including private/personal care homes and long-term care that provide essential patient information, including primary concern, past medical history, medications, functional and cognitive status, goals of care, contact information for care providers and next of kin. Regional implementation of such programs has been shown to enhance information-sharing, improve transitions of care and provider experience, e.g. Yellow Envelope program in Australia.[4]

- Enhance programs and relationships with programs that promote successful discharge from the ED:

- Identification of older people at risk in the community through routine ED screening, and subsequent implementation of enhanced community follow-up and supports. There are many tools the ED can use to identify older people at subsequent risk of decline; early assessment and intervention may prevent repeat ED attendances and enhance longevity of discharge.

- Access to short-stay community-based units that allow enhanced care for a brief period, while older people recover from challenges and functional decline associated with mild to moderate illnesses that otherwise do not require acute care.

- Timely access to responsive home-based care and support that can provide enhanced care upon discharge from the ED.

Disaster Readiness in the Geriatric Population

Older adults are more likely to face adverse consequences in times of natural disasters. This is in part due to mobility impairments, decreased sensory function (vision and hearing impairment), pre-existing medical conditions, and pre-existing social vulnerabilities.[5]

It has been suggested that to be successful in a disaster situation, three levels of target preparedness and intervention should occur by older people. These include:

- Personal education to the person and their family/caregiver.

- Establishing agency with existing care services that can be enhanced during disasters, such as meal programs, transportation services, and home nursing programs.

- Incorporating older patients’ specific needs into the emergency management system at a community level.9

The American Red Cross recommends that older people have a clear understanding of their personal needs, including mobility and sensory devices, medication and medication information, medical equipment supplies, and clear communication plans, such as contact cards for family, and care providers.[6]

Application of Virtual Care Modalities

Telephone or video-based consultation has received increased attention and development since the COVID-19 pandemic however, its existence is not new. Virtual consultation and assessment have been present in specific populations for many years, including those in rural and remote places, as well as for people whose ability to leave their home environment is restricted (e.g. RaDAR and the Remote Memory Clinic, Saskatchewan and the Telemedicine IMPACT Plus Clinic – Geriatric Arm, Ontario).

The COVID-19 pandemic brought about an explosion of virtual health initiatives, including many aimed at better accessibility for at-risk seniors, preventing social isolation and loneliness, and improving access to specialist and multidisciplinary assessment for those who would otherwise struggle to obtain it. Population-wide telehealth services[7], such as the nationally available 811 (RN-led but provincially-run and includes varying models), became central fixtures for many to access testing, assessment and care. While several programs around the country that use telehealth triage/physician referral claim it results in significant ED avoidance rates, there’s little evidence to support this, especially in older service users. This may be because of the rapidity and necessity of their role, however more evidence and evaluation are needed to support these claims.

Despite this, we believe virtual care is here to stay, and will have an important role for many older people. Virtual care has been shown to reduce complications related to travel and distance, even in those with cognitive impairment.[8] It will likely be especially important in rural settings to enhance accessibility to specialized care and follow-up. However, careful patient selection and clinic set-up must be considered, as older people are often more complex, and virtual services lack the ability to perform physical examinations and gather nuanced data that only in-person assessment might allow.

References

- Leaker H, Fox L, Holroyd-Leduc J. The impact of geriatric emergency management nurses on the care of frail older patients in the emergency department: a systematic review. Canadian geriatrics journal. 2020 Sep;23(3):250.

- Cherniack EP. The impact of natural disasters on the elderly. Am J Disaster Med. 2008 May-Jun;3(3):133-9. PMID: 18666509.

- Fernandez LS, Byard D, Lin CC, Benson S, Barbera JA. Frail elderly as disaster victims: emergency management strategies. Prehospital and disaster medicine. 2002 Jun;17(2):67-74.

[1] Reasons Patients Choose the Emergency Department over Primary Care: a Qualitative Metasynthesis, Vogel JA, Rising KL, Jones J, Bowden ML, Ginde AA, Havranek EP. Reasons Patients Choose the Emergency Department over Primary Care: a Qualitative Metasynthesis. J Gen Intern Med. 2019 Nov;34(11):2610-2619. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-05128-x. Epub 2019 Aug 19. PMID: 31428988; PMCID: PMC6848423.

[2] Reasons Patients Choose the Emergency Department over Primary Care: a Qualitative Metasynthesis, Vogel JA, Rising KL, Jones J, Bowden ML, Ginde AA, Havranek EP. Reasons Patients Choose the Emergency Department over Primary Care: a Qualitative Metasynthesis. J Gen Intern Med. 2019 Nov;34(11):2610-2619. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-05128-x. Epub 2019 Aug 19. PMID: 31428988; PMCID: PMC6848423.

[3] Leaker H, Fox L, Holroyd-Leduc J. The impact of geriatric emergency management nurses on the care of frail older patients in the emergency department: a systematic review. Canadian geriatrics journal. 2020 Sep;23(3):250

[4] https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/sites/default/files/2019-06/transfer_to_hospital-envelope_template.pdf

[5] Fernandez LS, Byard D, Lin CC, Benson S, Barbera JA: Frail elderly as disaster victims: emergency management strategies. Prehosp Disast Med 2002;17(2):67–74.

[6] Emergency Preparedness for Older Adults, https://www.redcross.org/get-help/how-to-prepare-for-emergencies/older-adults.html

[7] 811 healthlines: Newfoundland and Labrador: https://www.811healthline.ca/medical-advice-and-health-information/ : PEI https://emci.ca/integrated-health-programs/ : SK https://www.saskatchewan.ca/residents/health/accessing-health-care-services/healthline

[8] https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fneur.2021.761965/full

Appendix 5: The Facility-Level Accountability Framework

|

This facility-level framework addresses the patient journey into and through acute care facilities. While the system level framework is largely conceptual, the facility-level framework provides concrete strategies to make patient care accountability a reality, and increases the likelihood that patients receive the right care in the right place. It discusses accountability zones, program transitions, bottlenecks, triage, reverse triage, and high-value care, with the goal of mitigating ambulance offload delays, emergency access block and hospital access block. It recommends a compact indicator set to track accountability performance.

Patient queues appear at consistent locations in acute care settings. Queues represent care bottlenecks and unmet needs. The EMS-ED (Emergency Medical Services-Emergency Department) transition is a critical bottleneck, where constraints include the triage process and the unavailability of ED care spaces. The ED-inpatient transition is a second critical bottleneck, which is often limited by inpatient referral processes and by delayed transfer to an inpatient care space.

| Problem | Patient status | Queue Location | Patient need | Accountability | Process time goal |

| Emergency access block

|

Ambulance arrival | EMS stretcher | An ED care space | ED | 30 min |

| Walk-in arrival | Waiting room | An ED care space | ED | 0-60 minutes by CTAS level | |

| Hospital access block | Referred ED patient | ED stretcher | Disposition decision | Inpatient MD | 2 hours |

| Emergency inpatient | ED stretcher | Inpatient care space | Inpatient program | 2 hours | |

| Community access block | Referred inpatient | Hospital bed | Community-LTC | Community-LTC | 7 days / 4% ALC rate |

Table 7. Bottlenecks and Accountabilities

The ED Accountability Zone

Accountability Transition at the EMS-ED Interface

EMS provides prehospital care, not hospital care. EMS accountability ends at the time of ED triage, so patients on EMS stretchers fall within the ED accountability zone. It is an ED responsibility to manage these patients rather than leaving them under EMS care. Delays occurring after ambulance arrival relate to ED occupancy, process delays and to the actual offloading process. The ambulance offload time target is 30 minutes from arrival, which incorporates ED triage, registration, handover communication and patient offloading to an ED location. Offload location and speed will depend on patient status.

ED Accountability (“No Patient Left Behind”)

ED accountability means providing timely assessment and care, and having queue management strategies and surge contingency plans. EDs should adopt a no patient left behind mentality: patients should be triaged IN to care areas, rarely or never OUT to external waiting rooms or hallways. Triaging IN puts patients in the vicinity of care providers, facilitates recognition of severe pain or clinical deterioration, and makes ED staff aware of their queue.

The law of mass action states that the rate of a chemical reaction is proportional to the concentration of the reactants. This law applies to care systems, where the rate of a process is proportional to the concentration of patients queuing in front of it. If there are no waiting patients in view, there is less motivation to maximize efficiency, expedite discharges or implement innovative process change. [i] Allowing patients IN has other benefits: It reduces patient frustration and anxiety and allows patients to see that staff are doing their best to provide care. [ii,iii,iv] Conversely, diverting patients to external waiting areas puts them in an unsafe location (triage nurses cannot monitor waiting rooms), leaves them out of sight and out of mind for care providers, and gives ED staff an illusion of control that reduces the impetus to develop or activate adaptive responses and access contingencies.

Management By Closing the Door Promotes Stasis – Not Innovation or Efficiency

Triage In! Provide the Right Care in the Right Place

On arrival, CTAS 1 patients will go immediately to a critical care location. CTAS 2 and 3 patients should go within 30 minutes to a staffed ED care area, capable of providing necessary assessment and management. Triaging these patients to unstaffed areas like external waiting rooms or hallways should be tracked as a process deviation. Patients who have unstable vital signs, altered mentation or agitation, who are frail or incapable of sitting, or who have a possible life-limb threat based on triage assessment will typically go to an acute nurse-staffed stretcher. The same time goals and inflow principles apply to ambulatory self-referred CTAS 2-3 patients, and those arriving with police. Patients who are under arrest, agitated, flight risks, or who pose a threat to staff may require a period of police or security attendance.

CTAS 2 and 3 patients who can sit, and have no apparent life-limb threat, may be directed to an internal rapid assessment zone (RAZ) or intake area (see below). Patients with mental health problems may be placed in psychiatric assessment areas, while those with isolated orthopedic injuries, extremity pain, back pain, burns, wounds, contusions, eye problems and other low complexity single-system problems may be directed to minor treatment areas. Minor treatment is a more appropriate term than “Fast Track,” which may give patients unrealistic expectations.

Triage is often a bottleneck that can aggravate emergency access block and a priority for emergency care access initiatives.

|

You Can’t Push Patients into a Full Department!

It’s difficult to triage into a full department, but it’s worse to leave patients with potentially serious illness in unmonitored areas without assessment or care. Triaging out (caring for some patients while setting others aside) is an example of rationing. Current ED processes typically leave undifferentiated and untreated patients blocked in waiting rooms to assure optimal ongoing management for stable patients already in care. This is an example of paradoxical care allocation.[48] When demand exceeds capacity, thoughtful care allocation decisions are required. If care resources are limited, priority logically goes to patients with the greatest need. [2,16,49,50]

Matching care provision to need is challenging because patient need diminishes with the treatment provided during the ED visit. On their arrival, undifferentiated patients are high priority. They may be in pain or have occult serious illness that is undetectable during a triage evaluation (e.g., headache with subarachnoid hemorrhage or leg pain with necrotizing fasciitis). A dangerous resource allocation decision is if a stable patient is occupying a nurse-staffed stretcher awaiting repeat troponin results while a woman with a ruptured ectopic pregnancy is blocked in a hallway. This type of care maldistribution—which should be a never event—is in fact a regular occurrence.[48] It happens because we have become comfortable addressing demand-capacity mismatches by closing the door and leaving sick patients in queues.

| Ambulance offload time in the ED (from arrival to crew released) | 30 minutes |

| Time to ED triage | 10 minutes |

| Left without being seen (LWBS) rate | 2.5% |

| Time to ED physician, stratified by CTAS levels 1-5 | 0-120 minutes |

| EDLOS (Length of Stay) from triage to disposition (disposition refers to discharge or referral for admission) | CTAS 1-3: 4 hours |

| CTAS 4-5: 2 hours |

Table 8. ED Performance and Time Targets

ED Accountability: Challenges and Strategies

The Nurse-Staffed Stretcher Bottleneck

The nurse-staffed stretcher is the functional unit of the ED, and a key bottleneck server that is typically 100% occupied. The law of constraints tells us that flow can be improved by adding resources at bottlenecks or unloading bottleneck servers. [57,58]

Mitigating Strategies

Proactively Match Demand and Capacity [58]

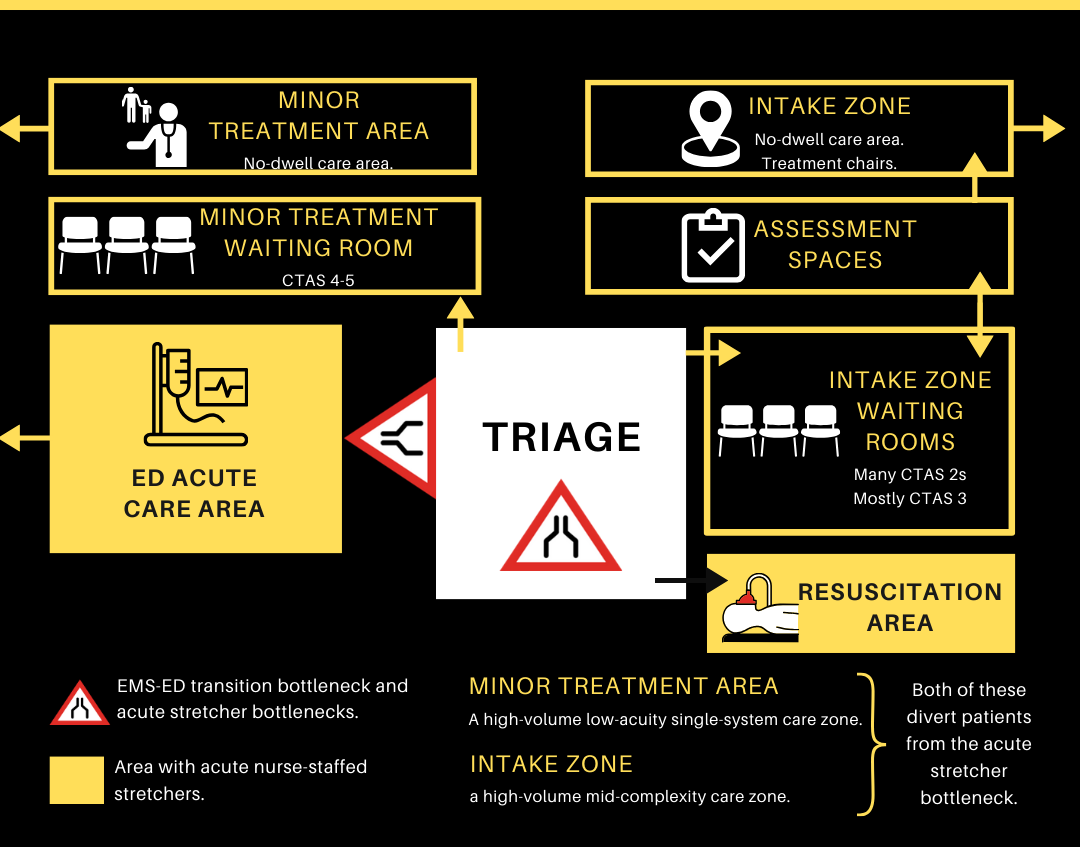

Emergency demand for a nurse-staffed stretcher is predictable: it’s highest in the afternoons and evenings, and lowest overnight. It’s higher on Mondays and lower on weekends. [31] ED managers should be aware of site-specific high-acuity inflow patterns and staff accordingly. This might mean reducing RN assignments overnight and augmenting evening coverage, or shifting hours from weekends to Mondays, or adding a nurse assignment on Monday morning to prepare for expected incoming volume. [13]

ED nurse-staffed stretcher capacity is profoundly altered by the need to manage boarded inpatients. This demand makes it more difficult to match emergency demand to capacity as recommended above; however, inpatient boarding patterns are also clear in the data. These staffing needs should be tracked and planned for, independent of emergency care. Boarding data will be invaluable for defining inpatient queues, and when considering innovative approaches to managing them—for example, medical assessment units (see below) or intake/capacity buffers on inpatient wards.

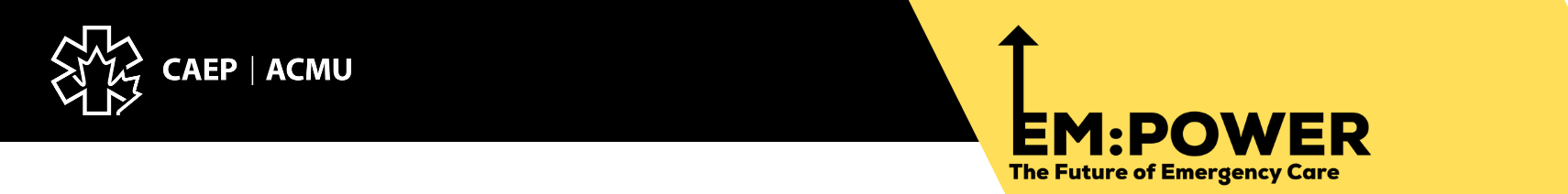

Divert Patients from the Acute Stretcher Bottleneck to Intake or Rapid Assessment Zones

Intake and RAZs are excellent diversion strategies for emergent and urgent patients. [v,vi] These are high-volume mid-complexity, no-dwell care areas with linked waiting chairs and treatment chairs (Figure 24). Most CTAS 2 and 3 patients are appropriate for intake or RAZs, assuming they are capable of sitting and have no apparent life-limb threat. Examples include abdominal pain, headache, dizziness, renal colic, chest pain, back pain. Rare patients are assessed in an intake zone and then upgraded to a monitored stretcher, but this is not a problem.

These areas typically employ a coordinating nurse (intake leader) who is responsible for prioritizing incoming patients and assisting with care activities. [68] Other nurses perform focused assessments and care, ideally in conjunction with physicians. Depending on department philosophy, nurse diagnostic and treatment protocols may be initiated. Intake patients are examined on a stretcher or exam table, then moved to a treatment chair if they need IV medications, or to a waiting chair if they require investigations. Patients do not own or dwell in a stretcher, which is the primary distinguishing feature from ED acute care areas. For this reason, high throughput is achieved using relatively few stretchers. Intake zones are distinct from minor treatment areas, which are high-volume low-acuity single-system care zones that specialize in minor trauma, burns, wounds, orthopedic injuries and EENT problems. Intake zones and minor treatment areas provide large buffer capacity to unload acute nurse-staffed stretchers.

Figure 22. ED Bottlenecks and Inflow Options

Advanced Triage

Advanced Triage is a good option when urgent or emergent patients arrive, and no acute care spaces are available. A physician can respond to triage, rapidly assess the patient, determine likely diagnosis and stability, and in many cases divert patients away from the nurse-staffed stretcher bottleneck to an alternate care location. [59,60,61] A motor vehicle accident victim with a spine board and collar might be quickly cleared to a minor treatment stretcher or waiting area, and a stable patient with possible appendicitis might have imaging initiated and go to an intake waiting location, rather than an acute stretcher. Advanced front-end provider response adds precision to the triage determination and reduces time to provider in concerning cases. [62]

Triage and Reverse Triage

Triage and Reverse Triage are strategies to free up care capacity under high occupancy conditions and to match available resources to patient need. Within each ED area, care allocation decisions are made using a series of ongoing triage and reverse triage decisions. In this context, triage means directing resources to patients in the accountability zone who have the greatest need—often those in the queue. Reverse triage means redirecting resources away from patients whose need and benefit have diminished, or withdrawing care resources that are no longer required. [54,55,56] For example, moving a stable chest pain patient out of a monitored stretcher to a waiting chair, discharging patients whose imaging study can be performed as an outpatient tomorrow, or allowing patients with renal colic to receive fluid and analgesics in a chair while awaiting their CT. If immediate testing will not change the patient’s outcome, it can be deferred.

Surge Contingencies and Protocols

EDs should develop surge contingencies, including physician and nurse call-ins, accelerated discharges, or even temporary reassignment of minor treatment staff and stretchers to acute care roles (review the disaster plan for other ideas). ED managers should match care provision as much as possible to expected variation (e.g. high Monday inflow) in patient demand by adding or reducing flex capacity. [13] During full occupancy situations with no stretcher availability, patients may be diverted briefly to alternate acute care locations (e.g., resuscitation or triage stretchers) until an appropriate care space can be opened. Surge protocols to move admitted inpatients to appropriate inpatient units should be activated when necessary. Refer to Appendix 6, Overcapacity Protocol, for details.

Proactive Ambulance Redirection

Many systems allow EDs to mitigate volume surges by initiating ambulance diversion. This usually requires meeting diversion criteria but it is reactive, prone to gaming, may occur inequitably despite similar crowding conditions in multiple departments, complicates care by delivering the wrong patient to the wrong site, and is one more example of management by blocking access. If EMS diversion is used as a surge contingency, it should be done with the goal of smoothing demand across facilities, it should be initiated centrally rather than by a stressed facility, and it should be based on real-time EMS arrival and offload data. Several cities have such systems in operation.

Reduce LOS (Length of Stay) by Addressing Physician Bottlenecks [58]

Reducing stretcher dwell time and overall EDLOS are other ways to free up ED capacity. LOS reduction requires focus on two physician-dependent intervals: door-to-doctor and doctor-to-disposition. Physicians are the ED’s most expensive resource. Like triage nurses, they are a bottleneck resource, usually 100% occupied. Based on the same concept of matching capacity to demand, physician staffing should be matched to known ED inflow patterns, which are highly predictable. Because physicians do not like to be inactive during shifts, they tend not to overstaff low periods, but they may understaff high periods. Fixing the physician bottleneck may mean:

- Adding physician hours during predictable high-volume periods, or

- Flexible shifts with early call-in and go-home options, or

- Physician surge shifts (short unassigned shifts during busy periods that physicians can sign up for in advance), or

- Even on-call coverage.

Adding physician hours has cost and HR implications. Another important approach to the physician bottleneck is to unload MDs by shifting nonclinical and administrative tasks to other providers. As bottleneck servers, the physician role should be limited to making diagnostic, treatment, and disposition decisions, and performing procedures. Better integration of nurse-physician activities to improve teamwork, or adding clinical assists like physician assistants, nurse practitioners or scribes,[1] are options.

Changes in ED case mix profoundly affect ED operations. Patients with complex chronic disease, mental health and addictions, frail elderly, and patients with homelessness or other complex social concerns now depend disproportionately on ED care. These complex patients now outnumber traditional “emergency patients,” fall outside the usual ED physician scope of knowledge, require more time than ED physicians can offer, and their care requires awareness of community resources that ED physicians do not possess. In the spirit of unloading bottleneck servers, hospitals can substantially enhance flow by assuring that relevant geriatric, homecare, mental health and addictions expertise is available in the ED to support these patient groups.

Improving doctor-to-disposition time means reducing time-consuming or deferrable investigations, improving turnaround times for necessary investigations, and using the simplest effective treatment approaches (e.g., oral rather than IV rehydration, fewer IV medications, and fewer first-dose drug dispenses if a community pharmacy is open). Research is convincing that ED physician decisions to refer, to perform CT or to perform ultrasound imaging are powerful drivers of prolonged EDLOS.vii Consultation for patients requiring hospitalization is unavoidable but ED physicians should question in other cases whether immediate specialty consultation or advanced imaging is necessary or whether these can be deferred to an outpatient setting. The causes of physician-related delays vary across facilities, and there are a multitude of improvement possibilities. This author suggests a site-specific improvement team to brainstorm the best approaches to these two key ED time intervals.

The Inpatient Program Accountability Zone

Accountability Transition at the ED-Inpatient Interface

Extended admitted patient LOS in the ED (boarding) is the number one cause of ambulance offload delays, the #1 threat to emergency care access,[31] and the number one operational priority for EDs in high-income countries. [18,38, viii, ix, x, xi, xii] EDs deliver emergency care, not inpatient care. ED accountability ends at the time of an admission order, which means admitted patients in the ED fall within the inpatient accountability zone. It is an inpatient responsibility to manage these patients, rather than leaving them under ED care. Care delays at the ED-Inpatient transition are ubiquitous and often prolonged. These relate to the inpatient referral process, the inpatient transfer process and high hospital occupancy rates.

Inpatient Accountability (No Patient Left Behind)

Inpatient accountability means providing timely assessment and care and having queue management strategies and surge contingency plans. Like EDs, inpatient programs should adopt a no-patient-left-behind mentality. Admitted patients should be rapidly transferred to the right care areas.

A root cause of ED boarding is the decoupling of queue management accountability from operational expectations: programs are not expected to be accountable for their waiting patients.[15] When a hospital program determines they are unable to manage their queue, the default process is to stop inflow and board inpatients in the ED. If hospital programs close beds for budgetary reasons—to allow staff vacations (seasonal closures) or because of sick calls—the unstated assumption is that the ED will simply hold more inpatients. If an inpatient discharge is delayed from 0900 until 1600 hours, one more ED stretcher will be blocked for the day.

For patients referred to an inpatient service, the ED-inpatient transition interval has two components. The consultation interval, reflecting consultant response, is measured from consult request to disposition decision (an admit, discharge or transfer order). This is a shared ED-consultant accountability period. The inpatient transfer interval reflects program and operational responsiveness and is measured from admission order to unit transfer. The target time for each interval is 2 hours, a total of 4 hours from consultation to unit transfer. A 4-hour target from ED triage to consultation and a 4-hour target from consultation to unit transfer means a cumulative 8-hour target for admitted patient LOS in the ED. Inpatient time targets were summarized in Chapter 7.

The Consultation Interval

The first bottleneck for ED patients awaiting inpatient care is the delay from consult request to admit order, which may last many hours. [xiii] Consultation delays have major operational impacts. In a hospital that admits 20,000 patients per year, a mean 3-hour consult decision time (vs. 2-hour target time) means 20,000 hours of lost ED capacity—enough to treat ~5,000 additional ED patients who are blocked in waiting rooms. Similarly, a 12-hour EDLOS, compared to an 8-hour target LOS, means 80,000 hours of lost ED capacity—enough to treat ~20,000 more ED patients (see Table 9).

| EDLOS for admitted patients | ED stretcher hours used | Opportunity cost |

| 4 hours | 80,000 | 20,000 ED visits |

| 8 hours | 160,000 | 40,000 ED visits |

| 12 hours | 240,000 | 60,000 ED visits |

| 16 hours | 320,000 | 80,000 ED visits |

| 20 hours | 400,000 | 100,000 ED visits |

Table 9. Effect of Prolonged Inpatient Boarding on ED Operational Capacity

**In a hospital with 20,000 admissions per year and ED processing time of 4 hours/patient

The most efficient consultation process involves attending-to-attending discussion and immediate admission order, followed by trainee assessment if necessary. Another acceptable process is to have a decision-maker (attending physician or senior house staff) perform a rapid assessment to assure patients are appropriate for their service, then write an admitting order and assign junior staff to do further evaluation and complete treatment orders.

In specific instances (e.g., hip fracture, large kidney stone with intractable pain, etc.), consulting services may prefer that the ED initiate admission and enter holding orders to avoid a disruption in the operating room or a 3:30 am telephone discussion. Consulting services can customize the process to suit their needs, as long as they are achieving negotiated time targets. Strategies to address consultation process challenges are summarized in Appendix 6. Special consultation considerations include house staff involvement, inpatient service caps, off-hours referrals, unclear need for admission, desire to avoid brief admissions, wrong service (Goldilocks) referrals and batch referrals.

The Inpatient Transfer

The delay for admitted patients being moved to an acute inpatient bed is the greatest flow constraint and therefore the number one priority problem. [18,31,38,71,72,73,74,75] The theory of constraints says that until this delay is addressed, other efforts to improve efficiency, reduce waiting times, ED lengths of stay and ambulance offload delays will have limited benefit. The table above illustrates the profound effect of ED boarding times, where even a one-hour delay in inpatient transfer is operationally important, and each four-hour increase reduces ED care capacity by ~20,000 patient visits per year. Small flow improvements have a profound effect on emergency care access.

The law of mass action states that the rate of a chemical reaction is proportional to the concentration of reactants. This law is relevant to care systems, where the rate of a process is proportional to the concentration of patients queuing in front of it. If programs can address inflow challenges by closing the door, leaving waiting patients out of sight and out of mind, there is less motivation to optimize processes, expedite discharges or implement innovative change.[1] Unit staff develop an illusion of control that reduces the need to initiate adaptive responses and contingency plans. Expediting access despite high occupancy introduces an evolutionary stressor that drives innovation and improvement.

Timely transfer puts incoming patients in the vicinity of the right care providers, reduces treatment delays, improves outcomes, and makes inpatient staff aware of patients queueing for their care. Timely transfer also reduces patient frustration and anxiety. Research shows that, facing care delays, patients would rather be in inpatient hallways than in ED waiting rooms. [ii,iii,iv,12] Conversely, blocking admitted patients in ED stretchers leaves them with the wrong providers in a noisy chaotic environment where the lights never go out, where there is no privacy, limited bathroom access and little opportunity for sleep.

You Can’t Push Patients into a Full Hospital!

It’s not ideal to push patients into a full hospital, but it’s safer than leaving undefined and seriously ill patients outside without care. When patient need exceeds care capacity, rationing is inevitable and thoughtful allocation processes are necessary. Priority for limited resources logically goes to patients with the greatest need and those who will experience the greatest benefit. [2,16,49,50]

Matching care provision to patient need is challenging because need diminishes based on treatment provided during the hospital stay. Incoming patients with acute illness or injury are high priority. Early in their stay, these patients benefit from advanced expertise and aggressive or interventional care. As they improve, the transformation to wellness continues but illness severity (need) and treatment intensity (benefit) diminish as inpatient time progresses.[48]

Whether the diagnosis is myocardial infarction, hemothorax or hyponatremia, patient need and benefit are front-loaded. Ironically, hospitals often allocate care resources in a paradoxical fashion, leaving [1] incoming acutely ill patients blocked in ED stretchers and waiting rooms in order to assure ongoing optimal management for stable patients already in care. If a stable patient is occupying a semi-private room awaiting a nuclear scan, a rehab bed or a ride home while a patient with undiagnosed sepsis is blocked in a hallway, this is a dangerous resource allocation decision that is incongruent with accepted ethical principles. [2,16,49,50]

This type of care maldistribution is common and causes many adverse patient outcomes. [18] Recommended inpatient accountability time and flow targets are summarized in Table 10.

| Consultation interval (referral to disposition decision)* | 2 hours |

| Inpatient transfer time (admission order to unit transfer)* | 2 hours |

| EDLOS for admitted patients | 8 hours |

| Mean hospital discharge time (with scheduled departures)* | 11:00 am |

| Actual LOS/Expected LOS* | 96% |

Table 10. Inpatient Performance and Time Targets

Note: *Denotes critical access and flow target.

Inpatient Accountability: Challenges and Strategies

The Inpatient Bed Bottleneck is the primary hospital bottleneck. Operations management principles tell us to add resources at bottlenecks or unload bottleneck servers whenever possible. [58] Adding beds may be necessary in some settings, but other approaches provide benefit at lower cost. These include optimizing flow processes, providing the right care in the right place (appropriateness), matching capacity to demand, reducing avoidable demand (i.e. shifting care activities to outpatient settings), limiting demand variability (smoothing), reducing low-value care activities, optimizing hospital LOS, and improving outflow of ALC patients to community.

Mitigating Strategies

Optimize Flow Processes

Demand and capacity are primary determinants of access, but process speed and differential flow rates have dramatic effects on emergency and hospital crowding. ED inflow times are measured in minutes, while ED outflow to the hospital is measured in hours with an EDLOS target of 8 hours. Rapid ED inflow associated with slow hospital inflow is a recipe for inevitable severe crowding—even if hospital capacity is sufficient to address demand.

This type of flow mismatch predictably overwhelms EDs every day, beginning around noon and ending after midnight when sufficient time has elapsed to allow equilibration. [31] Flow differentials cause emergency access blocks, care delays, waiting room disasters and a constant sense of crisis. This phenomenon is easily confirmed by touring your ED between 3pm and 8pm, when you will find a war zone with EMS stretchers lined up in hallways and crowds of sick patients blocked in waiting rooms (Figure 25). Repeat the same tour between 3 am and 8 am, after flow equilibration. The hospital bed count has not changed, but you will find a calm ED environment with no EMS crews waiting, and every patient in a care space.

Figure 23. Effect of Flow Differentials on Emergency Access Block

*Rapid ED inflow early in the day and slow ED outflow until later in the day lead to predictable overcrowding conditions on a daily basis.

Donald Berwick, President of the Institute for Healthcare Improvement stated that, “Flow is every bit as consequential for the health of our systems and the well-being of our patients and deserves the same strategic prioritization as safety.” [13] Optimizing flow processes will eliminate a substantial proportion of what appear to be capacity shortfalls without changing hospital capacity. It’s unlikely inpatient units will be able to match ED inflow rates. However, the same effect may be achieved by rapidly flowing admitted patients out of the ED into intake (buffer capacity) areas on inpatient units or to medical admission units that are designed to achieve rapid intake and subsequent controlled outflow distribution to inpatient units. Each of these options has the effect of moving part of the inpatient queue into an area of inpatient program control.

Modify Capacity

Programs that depend heavily on emergency departments to manage their patients may do so because of efficiency challenges, capacity shortfalls, poor flow processes, or all of the above. Achieving program accountability may require re-evaluation of program capacity, thoughtful assessment of the resources necessary to meet the needs of their target population, adjustment of hospital bed maps, or even new investment (program right-sizing), assuming there are demonstrated high levels of program appropriateness and efficiency. Even if no overall capacity increase is provided, programs should adjust capacity to match known variability in day-to-day and seasonal patient demand—for example, operate intake beds for morning admissions and open “swing” beds during anticipated surges. [13]

Day-Ahead Demand Capacity Matching [13]

Because emergency admissions are so predictable, day-ahead demand-capacity matching is an important strategy. Program leaders should ensure that each unit or clinical area has capacity for new patients at the beginning of each day and, specifically, that they are prepared to accept incoming elective patients as well as predicted emergency admissions. The expectation to create enough inpatient space for anticipated next-day demand should be incorporated as a key accountability strategy.

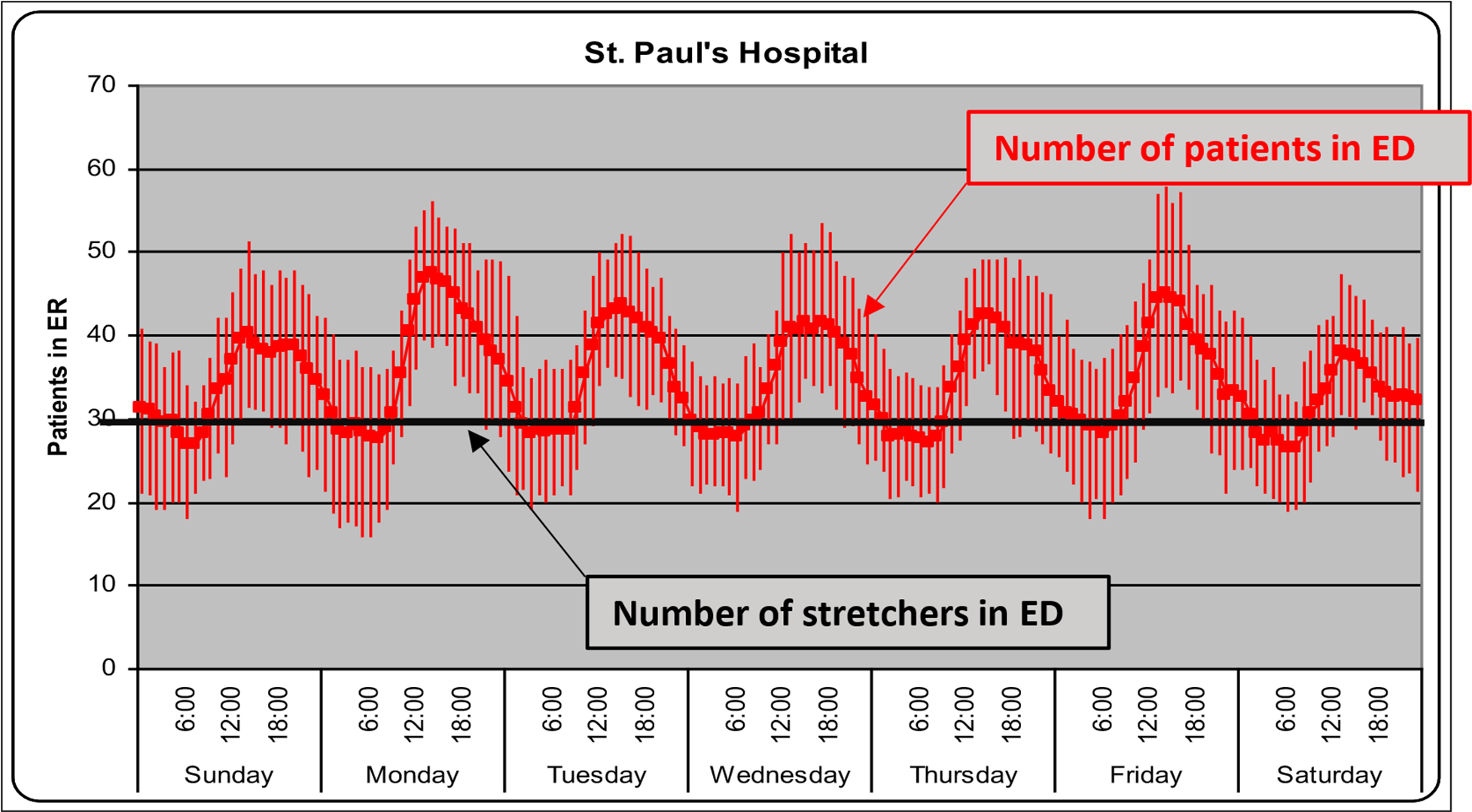

Reduce Demand on Inpatient Beds

Clinical Decision Units (CDU) and Medical Assessment Units (MAU) [13, xv]

CDUs can prevent brief avoidable hospitalizations. MAUs can serve as rapid ED outflow destinations and flexible buffer capacity to reduce stress on inpatient units. Rather than pushing patients to the wrong units during surges, which creates inefficiency for inpatient services, patients can be temporized in an MAU until the right unit has an available bed. MAUs can investigate, diagnose, treat and discharge (or admit) patients. They can arrange discharge to next-day specialist or clinic appointment, and they can prioritize high impact care pathways (e.g., frail elderly short stay). MAUs can be combined with CDUs to create a powerful hospital care resource, or they can limit themselves to providing flexible buffer capacity during high inflow periods. The value of these units will differ depending on underling capacity and efficiency factors and how they are used. For example, if MAUs are managed like standard inpatient medical units they will fail.

|

Optimize Hospital Outflow

Achieving hospital LOS targets is essential to improve patient flow into and through the hospital. Better discharge processes can free up substantial hospital capacity. This is not news. Most hospitals have decades’ worth of discharge planning initiatives behind them. Important themes include:

- Scheduled discharges

- Early discharges

- Weekend discharges

- Discharge checklists

- Structured discharge huddles

- Discharge display boards summarizing barriers to discharge (and how they will be addressed), discharge coordinators, and

- Bed utilization nurses to identify ALC patients and investigate prolonged LOS.

Most front-line nurses and physicians are more attuned to the patient in front of them [1] than they are to other waiting patients, to flow optimization or to discharge processes. When access blocks and care delays are not immediately apparent to them, they may resist flow and access improvement initiatives, seeing these as not patient-focused. These initiatives are constantly working against gravity and require substantial leadership involvement, energy input, staff education and ongoing communication to succeed and be sustainable. [80]

Utilize Alternate Admitting Destinations

When the most appropriate inpatient unit is full and generating a queue, patients may be diverted to similar units (e.g., medical to medical) or occasionally to unlike units (medical to surgical). These options and overcapacity care concepts are discussed further in Appendix 6: Overcapacity Concepts and the Overcapacity Protocol.

ED Holding

The objective of an accountability framework is not to empty out emergency departments; it is to assure patients can access necessary care. This framework therefore does not suggest that all admitted patients must leave the ED. In the interest of program collaboration, there are times when it makes sense for a program—usually the ED—to continue caring for patients who have transitioned out of their accountability zone. [xvi] For example, if an ED is not operationally stressed and has capacity to accept incoming emergent and urgent patients, they might continue caring for admitted patients until an appropriate inpatient bed becomes available. Limits to ED holding are discussed further in Appendix 6, Overcapacity Protocols. [xvii]

Figure 24. Unloading the Inpatient Bed Bottleneck: Gray arrows are default pathways to inpatient beds (primary hospital bottleneck). Black arrows are strategies for decompressing inpatient beds. * = pathways activated during OCP activation. A specialist in the ED can provide options to convert many admissions into discharges (D/Cs). CDUs can prevent brief avoidable hospitalizations and MAUs can serve as rapid inpatient inflow destinations and flexible buffer capacity.

Triage and Reverse Triage

Triage and Reverse Triage are methods of reducing demand on hospital beds and matching demand to available capacity. In this context, triage means identifying the sickest patients in the accountability zone (not just those already in care) for expedited care. Reverse triage means redirecting resources away from patients whose need and benefit have diminished or withdrawing care resources that are no longer required. Both are strategies to improve the balance of care delivery and reduce delays for sick patients. Reverse triage can free up substantial hospital resources. Although this is counterintuitive to providers who believe it is never appropriate to limit care, there are strong arguments, previously described, supporting reverse triage as a mechanism of freeing up care capacity. [53,54,55] Programs should reassess patient needs and adjust care delivery on an ongoing basis to manage demand, free up capacity, and match available resources to patient need.

Specialist in the ED

Urban ED physicians can initiate specialty referral for admission but generally have poor access to immediate specialty consultation. Patient problems (particularly in tertiary centres) are sometimes too complex to allow discharge after a brief ED assessment; however, the availability of a real-time ED specialist assessment /management /follow-up option can convert many admissions into discharges.

Reduce Demand Variability (Smoothing)

Failure to control system variability is a major cause of access block. [13,47, xviii, xix, xx, xxi] Natural variability (e.g., influenza outbreaks) and scheduled variability (e.g., surgical admissions clustered early in the week) generate large fluctuations in bed demand. [31] High variability increases demands on many services, including lab, imaging, and ICU. [47] Service- and provider-related LOS variation, weekday/weekend variation in admissions and discharges,[i] seasonal bed closures, staffing shortfalls, diminished consultant availability and plummeting hospital discharge rates on weekends—as well as lack of palliative or LTC intake outside of short working day bankers’ hours—mean that system capacity is also highly variable and unmatched to patient demand.[31] All of these factors are sensitive to better demand management and inflow planning.[83]